12 May 2017

The 2013 Bingham Canyon mine failure: insights into the giant Manefay landslide

Posted by Dave Petley

The Bingham Canyon failure: insights into the giant Manefay landslide

At 9:30 pm on on 10th April 2013 a huge landslide occurred in the Bingham Canyon copper mine in Utah. I covered this event at the time, and much has been written since. The two failure events that evening had a total volume of between 65 and 70 million cubic metres, one of the largest non-volcanic landslides in North America. The failure, sometimes termed the Manefay Landslide, caused extensive damage to the mine and of course vast economic cost. An interesting aspect of the landslide was the very limited information from the operators, Kennecot Utah Copper / the Rio Tinto Group, about the event at the time. They had clearly anticipated the failure as the location of the landslide was evacuated before the slide. However, they also appeared to have underestimated its likely size and mobility as large amounts of heavy equipment in the mine were damaged.

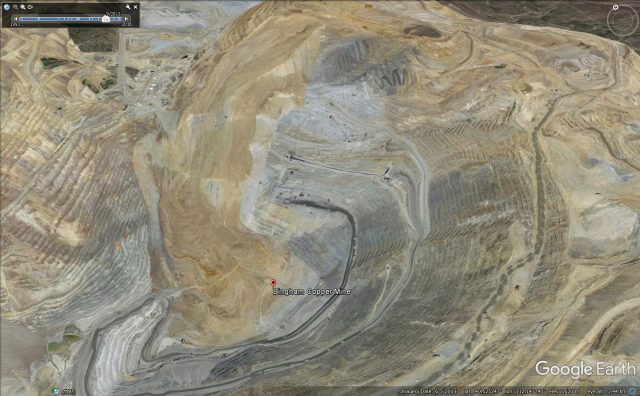

This Google Earth image captures the scale of the Manefay landslide:

Google Earth image of the Manefay landslide at Bingham Canyon mine

I discovered yesterday that Brad Ross, who “led the team charged with developing the geotechnical studies and mine planning to demonstrate the long-term viability of the mine” has written a book, Rise to the Occasion, that “tells the dramatic story of the men and women who safely led Utah’s 107-year-old Bingham Canyon Mine through the largest mining highwall failure in history”. Brad has put a post on his website about the failure event that is extremely insightful. First, he notes that they predicted the failure two months before the collapse, allowing the evacuation. But, as he puts it:

predicting how the Manefay would fail did not go nearly as well, resulting in damaged and destroyed equipment.

and

The way that the Manefay failed was a surprise as it traveled much further and faster than anticipated. Anything in the path of the enormous mass was either destroyed or was simply picked up and shoved out of the way. This resulted in the damage and destruction of three large mining shovels (including a P&H 4100C), thirteen 320 ton haultrucks, three drills as well as a multitude of spare parts, support equipment and supplies.

Brad notes that the geotechnical team at the mine had extensive experience of failures in the pit, but that these were mostly wedge or circular failures. Their anticipation of the Manefay landslide was that it would be similar, whereas it was an active/passive block failure, that therefore behaved differently. In particular the landslide was faster and more mobile than they anticipated. Brad notes that these preconceptions might have been avoided had external experts, who might have been more open to thinking through different failure mechanisms, been involved. But he also notes that this event was so extreme that it is likely that no-one could have foreseen its behaviour.

Brad praises the operators for being willing to share their experiences in this way, and I for one welcome the insights that this event is now providing.

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.

Tremendous job, as I have come to expect, and regularly share in ongoing dialogues with people I have worked with since the ’60s. I have been fascinated by, and in various ways, visited that mine from 1962 through 1997. NEVER within the pit, but ‘jeeping’ near the west rim without getting caught. My only, peripheral, geotech involvement was in relation to their tailings ponds near Magna. I really need to add more landslide experiences to what I’ve written about. [Never trust a silt.] Highest regards! Mike

The 2013 Bingham Canyon mine failure: insights into the giant Manefay landslide

I really liked your site. Thanks for the information.

I was there the night of the manefay slide. I was in the truck shop the night before. The people in charge caused that slide. By being greedy and taking chances.