3 May 2021

SciComm as Dialogue—not Monologue—in Appalachian Kentucky

Posted by Shane Hanlon

By Sarah M. Mardon, Maria E. Sanchez, Lauren E. Cagle, and William C. Haneberg

Damage from a tornado. Credit: Research participant

Want to reach out to nontraditional geoscience stakeholders? Have you wondered how to engage them or who they might be in the first place? A pilot project in a five-county area of eastern Kentucky is showing us at the Kentucky Geological Survey (KGS) how we can go beyond traditional science communication strategies to reach new stakeholders and help them solve problems in their communities.

Our research team recruited community members from the five-county area and asked them what they want to know about geology and geologic hazards in their area. University of Kentucky researchers William Haneberg, the KGS director and a research professor in the university’s Earth and Environmental Sciences Department, and Lauren Cagle, an assistant professor in the university’s Writing, Rhetoric, and Digital Studies Department, are leading the project. Cagle is an expert in scientific and environmental rhetoric. Our research strategy originally relied on a series of face-to-face meetings in each county during 2020 but, because of COVID-19, we pivoted to a completely remote approach. The first step was to produce a short video explaining geology, geological surveys, and how KGS resources might be useful. Our participants completed a short questionnaire after watching the video to help us get to know them. We then used open-ended responses from participant journaling, personal photos, and interviews to create a profile for each participant.

Geologists are comfortable analyzing all kinds of quantitative data, but our written, visual, and verbal data were far from numerical. We used the open-source qualitative data analysis program Taguette to code and analyze written and transcribed oral responses, as well as images participants provided to represent thoughts and feelings about their communities—a research method called “photovoice.” During interviews, we asked participants about their everyday communications processes and if their profiles accurately described their beliefs, opinions, and feelings. The qualitative analysis process uses data validation tools developed in the social sciences, helping ensure our conclusions are robust.

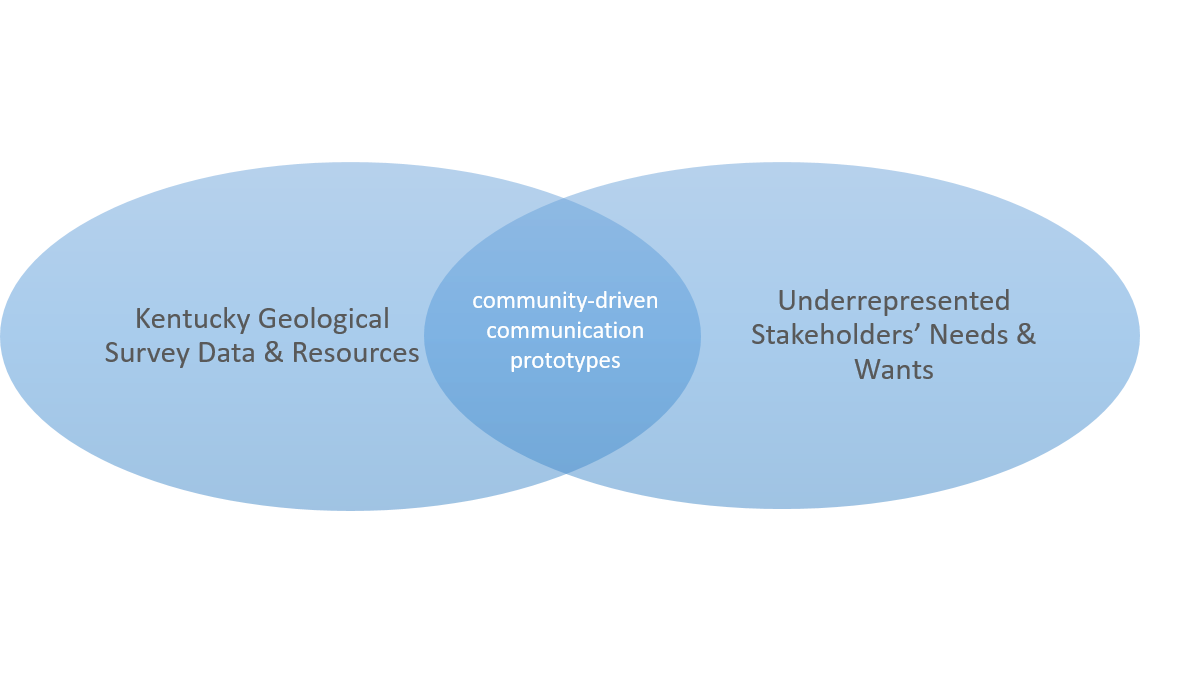

Visual representation of communication plan. Credit: Lauren Cagle

We learned that many of the community members enjoy spending time in nature and hiking, and would like to have a better way to identify the rocks they see on their hikes. To this end, we are developing a pocket guide to the geology of the region. We also designed a brochure highlighting KGS resources to help community members understand the information KGS has to offer. And, because many eastern Kentuckians have encountered landslides, we developed a chart indicating who they can contact about landslide-related questions.

The final stage of our work, which is now underway, is sharing these three communication prototypes and gathering feedback from the participants. Although our specific prototypes may not be relevant to all potential stakeholders in all areas, we are optimistic that our underlying approach of community-driven dialogue—as opposed to the one-way communications inherent in the more traditional information deficit approach—allows us to identify and engage people we wouldn’t have reached otherwise.

-Lauren Cagle is Assistant Professor of Writing, Rhetoric, and Digital Studies at the University of Kentucky. Find her on Twitter and via email. William Haneberg and Sarah Mardon work for the Kentucky Geological Survey. Follow them at @KGSNews. Maria E. Sanchez is a senior at the University of Kentucky. Contact her at [email protected].

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.