25 February 2020

Spatial and temporal patterns of landslide losses in Colombia

Posted by Dave Petley

Spatial and temporal patterns of landslide losses in Colombia

Back in 2012 I posted about the levels of landslide losses in Colombia, which is one of the most landslide prone countries, based on my fatal landslide database. I noted that levels of loss are high, especially in the western side of the country, and that Colombia needs to be a priority country if we are to reduce loss worldwide. It is good that the 13th International Symposium of Landslides will be held there later this year (COVID 19 permitting I guess), which will draw attention to the challenges in that country.

In that context, it is really good to see a new paper (Aristizábal and Sánchez 2019), published in the journal Disasters, which seeks to analyse losses from landslides in Colombia between 1900 and 2018. This is a truly epic piece of work – the authors have used multiple datasets at national and regional levels to record 30,730 landslides over the 118 year period of the study. As such this is one of the most detailed and comprehensive national landslide studies published to date.

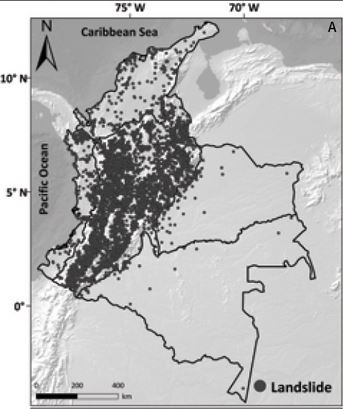

There is much to take away from this study, but I’ll highlight some of the more interesting findings. First, not unexpectedly, the authors found that landslides are concentrated in the mountainous west of Colombia, as the map below shows:-

The distribution of landslides in Colombia recorded by Aristizábal and Sánchez (2019).

.

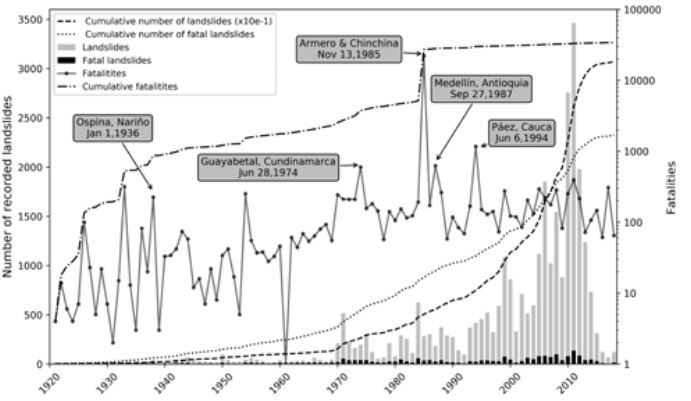

Of these landslides, 2,328 caused at least one fatality, with a total of 34,198 deaths. This is much higher than had been previously recorded. As always for these types of very long-term studies, the majority of landslide fatalities have occurred comparatively recently:-

Annual landslide occurrences and fatalities: the five most catastrophic events in Colombia, from Aristizábal and Sánchez (2019)

.

It is really interesting to note that landslides, and the resultant fatalities appear, to have peaked in about 2011 after showing a notable increase with time, and have declined substantially since then. So, for example, the number of recorded landslides was 3,545 in 2011 but just 123 for 2016. The reasons for this are not entirely clear; Aristizábal and Sánchez (2019) suggest that:

“This might be due to advances in risk reduction in Colombia, especially making legally mandatory implementation of the land use planning programme (Planes de Ordenamiento Territorial), but it is too soon to say for sure. Much more analysis needs to be conducted and more evidence acquired to prove and compare the effectiveness of such risk reduction policies.”

If this is the case then it would be one of the most impressive landslide hazard management programmes undertaken at a national level to date. However, I also note that 123 landslides in a year in a country such as Colombia seems low to me, so I wonder if this might in part be an artifact of the data.

This is an excellent and very welcome study, which provides insight into the levels of loss in Colombia. It would be good to see more studies of this type for other landslide-prone countries.

Reference

Aristizábal, E. and Sánchez, O. 2019. Spatial and temporal patterns and the socioeconomic impacts of landslides in the tropical and mountainous Colombian Andes. Disasters. DOI: 10.1111/disa.12391

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.