23 August 2010

Rocks of Glacier National Park

Posted by Callan Bentley

This is the second of my Rockies course student projects that I wanted to share here on the blog: it is a guest post by Filip Goc. Enjoy! -CB

—————————————————————————–

The Rocks around Glacier National Park, Montana: Introduction to the formations

The geology around Glacier National Park is great for beginners because the area is structurally straightforward and formations are generally easy to distinguish. Still, there is a lot to be excited about.

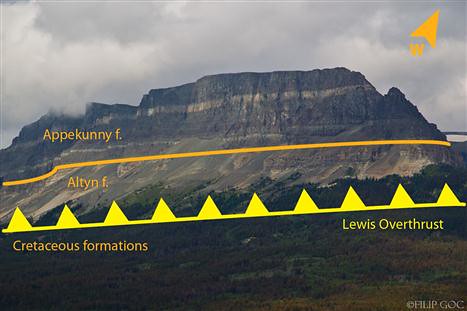

The rocks exposed firstly from the top down are old sedimentary rocks of the Belt Supergroup. It is called “Belt” after Belt, Montana, and “supergroup” because it is immense. These rocks were deposited in a Mesoproteozoic (1.6-1.2 Ga) sea basin, and show little to no metamorphism despite their age. Below belt rocks that make up the peaks of Glacier NP, there lay Cretaceous (~100Ma) shales; which brings us to the structure. How can these young shales get underneath MUCH older Belt rocks? Yes, there is a major thrust fault, and it is called Lewis Overthrust.

Simply put, the Belt rocks were first deposited in the sea basin. Then, Paleozoic rocks were deposited, but they are not exposed in Glacier NP, as they have eroded away. Then, Mesozoic rocks, including the Cretaceous shales and sandstones of the Western Interior Seaway, were deposited. Around 150-80Ma, as a result of the Sevier Orogeny, a HUGE slab of Belt rocks hundreds of miles wide and 15-18 miles thick slid over the Cretaceous formations more than 50 miles east! Slabs just love to glide on shales with their weak planes. Mr. Maitland from our group would call it the Banana Peel Principle, although most geologists who love French as much as I do prefer a much more refined term décollement horizon (yes, it is essentially a banana peel).

Check it out in this photo. The Belt rocks of the Altyn and Appekunny formations comprise the cliffs. They are much more resistant to erosion than the weak Cretaceous strata underneath them (low hills covered in trees). The striking white layer in the Appekunny formation is a quartzite bed.

Then erosion took the stage with its rivers and mass wasting. Finally, around 2 Ma the Ice Age came, and we derive the name of the park from the enormous glaciers that carved the peaks into their current shapes. The last of these huge glaciers melted ~12,000 years ago, and some people think the park should therefore be named Glaciated Park, ExGlacier Park, or just Glacier-No-More. The glaciers to be seen there today are young and tiny.

Glacier National Park is a great place to educate kids about geology because many formations can be identified by their colors. From old to young, there are Altyn (and Prichard), Appekunny, Grinnell, Empire, Helena (or Siyeh), Snowslip, and Shepard formations. Let’s get color-wise. First above the Lewis Overthrust are the light gray to white (or weathered into light tan) layers of limestone and dolostone of the Altyn formation. The Prichard formation exposed on the west side of the park is essentially of the same age as Altyn, but was deposited deeper, and is therefore darker as there wasn’t as much of oxygen in the depositional waters. It consists of dark gray to black argillite with slate-like appearance. (Argillite is slightly metamorphosed mudstone.) Then there is light green or burgundy argillite of Appekunny formation. Both versions have the same iron content, but the purple version is more oxidized. It was deposited closer to shore than Altyn. The Grinnell formation is the one dominated by burgundy argillite. The Empire formation is a transitional formation between Grinnell and Helena. Helena consists of medium to dark gray dolostone and limestone, often covered with honey-colored weathering rind. The Snowslip formation features red or green argillites, shades of orange or yellow, rusty colors, purple tones, white quartzite… pretty much “rainbow rock.” The Shepard formation is similar to Helena, gray limy rocks with orange buff.

Now for the fun stuff:

The Prichard formation is exposed on the west side of the park; is essentially of the same age as Altyn, but was deposited deeper, and is therefore darker as the increased pressure produced biotite. It consists of dark grey to black argillite with slate-like appearance. Aren’t these potholes beautiful? Also notice the joint sets. The diameter of the larger pothole is ~55cm.

There are great features to be seen in the Grinnell formation.

In this picture from McDonald Creek, there is cross-bedding in white quartzite, and a cross-section of ripple marks! A stream dumped sand onto muddy shore, ripples were created, and then mud leveled them out! Quarter for scale.

In this outcrop there are some mud cracks filled in with sand, exposed in cross section view:

There’s also cross bedding, and mud chip rip-up clasts. When the muddy shore gets exposed to the sun (low sea level), the mud dries up, loses volume, contracts, and cracks. That’s when a shot of sand came, probably with some rainstorm. Quarter for scale. As you can see in this picture of present-day drying mud, in the next stage mud cracks curl up:

Streams or waves can easily carry those “chips” away, and deposit them with sand. That’s the mudchip rip-up clasts. Very cool outcrop!

These are just another batch of nice mud cracks in Grinnell formation. Boot for scale.

This boulder has mud cracks overprinting ripple marks. Two in one! Swiss Army knife (11 cm long) for scale.

This one has it all. Cross bedding, mud chip clasts, ripples, and mudballs. Field notebook for scale.

These strange ripples in the Shepard formation are called interference ripple marks. They form when two currents go against each other at ~90°. Field notebook for scale.

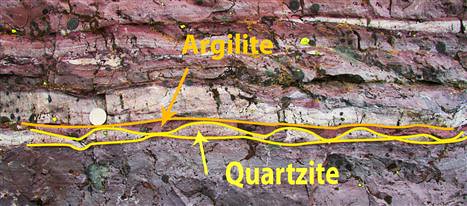

Folded argillite and quartzite of the Grinnell formation with preserved ripple marks. Car keys for scale.

A bit more of the structure within the Grinnell Formation. This beautiful faulted fold lies on the way to Grinnell Glacier. Field notebook for scale.

Here’s a fold that hasn’t yet been breached by a through-going fault. Width of field of view is about 30 cm.

Note on prominent RED color in Glacier National Park: These red beds above St. Mary Lake are Grinnell formation.

Within the Helena formation, there is a conspicuous layer of diorite with contact metamorphosed rock above and below it – the Purcell Sill.

Part of this piece of Purcell Sill diorite has been altered to make the green mineral epidote. The horizontal field of view is ~80cm.

So when one hikes in the area at or above Purcell Sill, all the Grinnell is way down in the stratigraphic column. The red mudstones exposed around the center of the park ( like around Logan Pass) are mostly of Shepard formation. They look a lot like Grinnell, but they are younger. The width of the rock in the foreground is ~ 1m.

Mudcracks in Shepard formation near Hidden Lake. The trail to the Hidden Lake has one of the thickest Shepard exposures in the park.

There is one more red formation, even younger than the Shepard. This is the Kintla formation. Most visitors don’t encounter the Kintla. It can be seen as a red cap on the tops around Logan Pass (even above Shepard.) There are also exposures around Waterton Lakes on the north side of the Canadian border, and, of course, around Kintla Lakes and Hole-in-the-Wall on the northwest side.

This cross-section of mudcracks at the Boulder Pass are possibly within Kintla formation or Shepard formation. It is really hard to tell without a precise geologic map. At any rate, it is NOT Grinnell. The width of the rock in the foreground is ~ 70cm.

Since we are at Boulder Pass, there’s also plentiful of typical Snowslip at the trail to Hole-in-the-Wall. This sample shows why the formation is called Snowslip (at least as far as I figure it). The glacial striations show what direction the “snow slipped.”

Sometimes there are areas of low oxidation called reduction spots.

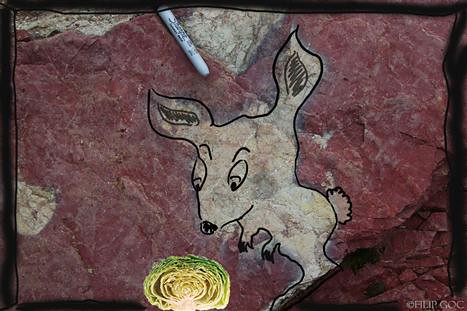

As the red color of Grinnell formation is caused by oxides of iron, non-oxidized Grinnell has a different color: the greenish Appekunny tone or shades of orange. There are whole greenish beds of reduction within Grinnell. The cool thing is that iron content is roughly the same throughout the rock! GAME for you: What do you see when you look at this reduction zone?

I see a very specific animal, and I know exactly what it is doing in there:

It is a bunny rabbit, and he is looking for stromatolites, or so-called “cabbage heads”!

So what is a stromatolite? Did the bunny choose the right formation to dig in? If not, what formation would be better?

Read on.

(Stromatolite layer along Going-to-the-Sun Road. The stromatolite layer is ~60cm high.)

Stromatolites are blue green algae or cyanobacteria that thrived on Earth in the Precambrian. The oldest stromatolite fossils on Earth are around 3.5 Ga. Stromatolites persist in the modern world in places where they are protected from grazing predators like snails. They were one of the first abundant photosynthetic organisms. They essentially remove CO2 from ocean; use the carbon for themselves while causing precipitation of calcium carbonate, and release the oxygen. They cover their cells with protective slime. When the slime gets too covered in sediment, they just grow a new layer, which results in dome-shaped layered “cabbage heads.” Stromatolites used to be so abundant that the sheer volume of oxygen they produced significantly changed the composition of our atmosphere. Stromatolites made our planet suitable for organisms like us!

Stromatolite beds are within many of Belt formations. The major stromatoliferous bed in Glacier National Park is the Helena formation. Some beds are in the Altyn and Snowslip formations also host stromatolites.

One of the best exposures of enormous stromatolites is at the Grinnell Glacier. Those honey-colored guys in Helena formation were ground down by the glacier so we can admire their cross-sections of their colony from the top. But first, a side view:

Here is our little group hanging out with the Helena stromatolites.

Notice the easily visible glacial striations!

This awesome 1.8m diameter stromatolite cracked in half!

In fact, this one was quite AGGRESSIVE, and had a DEADLY appetite.

Exposed at the Boulder Pass. Stromatolite in Shepard formation, as viewed from underneath. Stromatolites grow dome-shaped, but this is bowl-shaped. Therefore it is upside down. Field notebook for scale.

This exposure near Hole-In-The-Wall cirque I named “Stromatolite Wall.” All those columns you see are stromatolites. The wall is some 8m high (exposed).

This stromatolite weathered into a three-dimensional column! One can easily see the separate slime layers.

Another absolutely stunning stromatolite bed is in the Snowslip formation. It is not a thick one, but special. The Snowslip formation was deposited closer to shore than the Helena, and the algae had trouble living there. There was quite some amount of organic material and mud periodically dumped in. Stromatolites caught the mud with its load of minerals into the slime layers, and those minerals later stained the fossils. The result: RAINBOW STROMATOLITES (my term). Next time somebody whines about how stromatolites are boring blue green grandpas, sitting around for billions of years doing nothing, just show them these playful buddies.

Elsewhere in the Helena Formation, you can see halite casts:

These are features that form when evaporation concentrates the dissolved Na & Cl ions so that they begin to bond together and crystallize salt. Later, when the water level rises again, the halite dissolves away and mud can fill in the empty cubic mold:

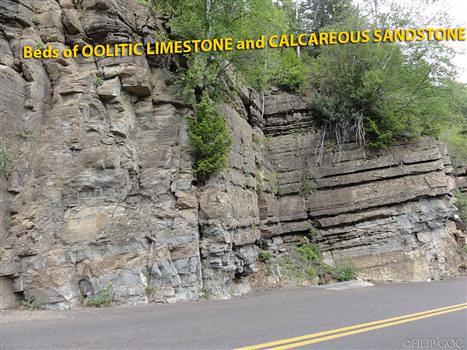

There’s one more interesting feature in the Helena formation. OOLITIC LIMESTONE. I made it uppercase because most people don’t see this in the park. It is exposed just next to the Going-to-the-Sun Road in the western part of the park.

In the photo, the gray beds are limestone, the brown ones are sandstone.

Oolites (also called ooids or ooliths) are little (0.25 to 2mm) round balls of limestone that for in warm shallow marine environments. The grain of limestone is gently rotated around by waves, and so the limestone precipitates in layers around the center…

If you look closely, you should see the oolites. They are ~0.5mm in diameter. Quarter for scale.

Although Glacier National Park is primarily famous for its jagged glacial landscape (and for a good reason!), the rocks that make up its horns and arêtes are remarkable as well. Despite having been displaced ~50miles east, they retained many of their primary sedimentary features. It’s common to spot beautifully preserved ripple marks or mudcracks. The abundance of fossil algae – stromatolites – is striking as well. Glacier National Park offers arguably one of the best Belt rock exposures in the US, which also makes it extraordinarily colorful. The deadly combination of colorful strata, white snow, and jagged peaks ensures the park is the one of the most scenic places around. It is just gorgeous up there.

—————————————————————————–

Filip now leaves NOVA; my Rockies course this summer was his final NOVA class. Now he’s off to the University of Virginia. Good luck, Filip! —CB

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

[…] student Filip Goc, who you may recall from his epic Glacier National Park guest post after our 2010 Rockies trip, is with me out here in California. While we were making our abortive […]

I have read this multiple times. I am on the back end of my Historical Geology class and I find myself often mesmerized by geologic formations. I have the most amazing teacher who has drawn me into geology so much I may go further into this field of study once I have finished my major (chemistry). Thank you for put this up with such great pictures. My seven year old son gets as mesmerized as I do when we read this article. Hoping to take a trip here in the very near future.

Hello

I visited Glacier NP in 2006. I took a foto from a fold that probably was formed by a granite laccolith intrusion. BUT I can not confirm this because I read that there is no granite in Glacier National Park. May I send the foto for you?

Sure; send it to me at cbentley (@) nvcc.edu – but could it just be diorite? (it looks a lot like granite)

Hi

I had a trip in Glacier in 2015 and I found this (and other) posts quite useful for a quick look at Glacier’s geology. I’m not used (I’m a geologist from Italy) to hit with my hammer such ancient rocks (the anciest usually starts from Permian up to Oligocene, with few strata from Devonian or Carboniferous/Missisipian in some small areas).

I was able to trace Lewis thrust and the many other faults in the park and to recognize, quite easily, the sedimentary rocks/formations along Going to the sun road and other trails. With a quite good view of Purcell Sill, hiking to Grinnel glacier trail and Garden Wall trail. Never seen rocks baked in this way along going to the sun road.

Thank you so much for your posts

Max Scarpa

Venice (Italy)

http://www.channeldb2.com/profile/MaxScarpa52

my family have been Kalispellians since 1880’s. I worked trail & wildfire in Glacier park in the late 1960’s. Now retired after 50 years of teaching Calif College Chem, I reminisce. I worked extensively in ’68 on the Cracker Lake trail. A photo of it on my March 2021 calendar greets my morning. I’ve been searching the net to find the name of the copper mineral # Cracker lake. can anyone help?