28 March 2014

The Oso (Steelhead) landslide: mechanisms of movement and the challenges of recovering the victims

Posted by Dave Petley

The Oso (Steelhead) landslide – mechanisms of movement

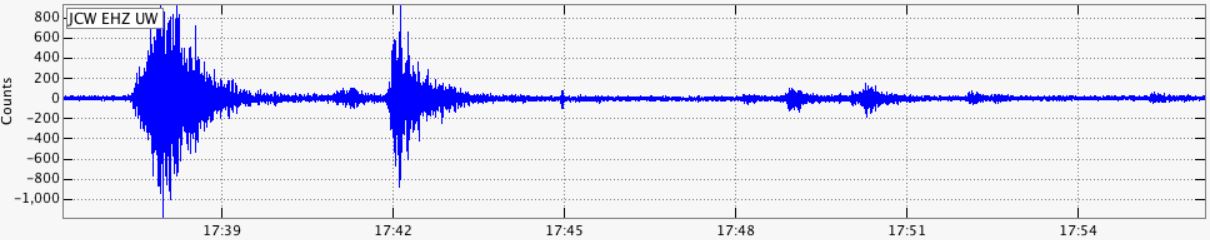

In the last three days the desperate search for the up to 90 missing people at Oso has continued (see my earlier post on the landslide). Survival rates for landslide victims are very short, so this is not a rescue operation any longer. During this time some very interesting information has emerged about the landslide in the form of a seismic record of the slide. There is an excellent blog post from Kate Allstadt about this seismic signal on the PNSN blog – their understanding of this data is much better than is mine, so I won’t try to replicate it here. For me the most interesting aspect is the double seismic signal generated by the landslide, which indicates two major movement phases (followed by lots of small slips, which we would expect):

Kate Allstadt via the PNSN blog

..

The start of the two movement events were about 4.5 minutes apart; the first lasted about 2.5 minutes, the second was somewhat shorter and less energetic (i.e. the movement rate was probably slower).

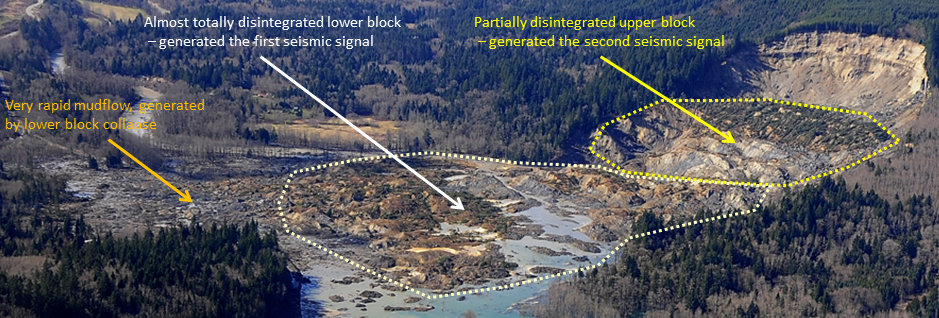

So what does this tell us about the landslide? We need to compare this with an image of the landslide after the failure – this Wikipedia image remains the best that I have seen for getting an overview of the whole landslide:

..

For comparison, I have tried to create a pre-failure view from Google Earth – this uses a Landsat image from last July:

..

To me the most logical explanation that ties the images and the seismic data together is a two phase movement event, as Kate Allstadt suggested:

The first movement event would have been a very rapid and violent collapse of a lower landslide block. I have labelled the remains of this block, now mostly broken up, on the image below:

..

This first collapse event would have generated a very rapid mudflow as it collapsed onto the sediments below – this may have caused most of the damage. The best video I can think of to illustrate this initial collapse event is the Po Selim tin mine landslide in Malaysia – although note that in the case of the tin mine the mudflow may have been more energetic due to the possible presence of pools of water in the floor of the quarry:

…

The violence of the process does, fortunately, suggest that the victims will not have suffered for long.

Recovering the victims

To date 25 victims have been recovered. This might seem low when there may be as many as a further 90 people buried in the debris. However, recovering victims from a mudflow is exceptionally difficult as the remains are likely to be deeply entombed in a material that has very low permeability. For this reason, the authorities may need to decide to preserve the site as a grave. If the search is to be continued, a very detailed mapping exercise will be needed. This will require three key elements:

- Attempts will be needed to identify where on the ground each victim was located when the landslide struck. Were they in their house, in a car on the road, etc. The better the initial location information the better the chances of finding the final resting place;

- The landslide mechanisms will need to be identified in great detail. Detailed mapping of the landslide will be needed to do this – the investigators will need to ascertain whether victims were pushed ahead of the slide, were entrained within it or were buried in situ. In my experience the latter is the least likely in this type of slide, but the patterns will vary across the landslide;

- Detailed mapping of the human debris will be needed. The remains of each structure will need to be mapped out. This will give key information about the dynamics of the landslide at each point, and of course it is also likely that many of the victims would have been close to, or within, buildings.

This is a time-consuming, challenging and sometimes dangerous task, and one that will not necessarily be successful. Generally speaking this level of work has rarely been undertaken, so it would push the boundaries of our knowledge. The authorities will need to balance competing pressures in determining a way to proceed. This may not be an easy, or a popular, choice.

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.

I was in charge of the planning the search operations in Oso Washington. I just read your blog where you detailed what would have to happen to find the victims. We did exactly what you wrote in your blog would need to be done to find the victims and we have recovered all but two of the victims.

We mapped where the survivors and initial victims were found. We searched the debris fields of building remanents and vehicles and found more victims. We searched specific locations based on K9 indications and found more. We plotted each find on the map then geo located where we believed each victim was at the time of the slide. Based on trajectories of each victim we were able to focus our search efforts in two distinct areas finding all but two of the missing victims.

Just thought I would let you know that we did this based on no prior experience in mudslide search operations but good solid Search Management theory. You are spot on when it comes to finding people in this type of event and we validated it with greater success than we could have ever imagined. We believe we will eventually find the remaining two people once we can dewater the areas we think they are in.