20 January 2020

Brumadinho: the Expert Panel report on the failure of the Feijão tailings dam

Posted by Dave Petley

Brumadinho: the Expert Panl report on the failure of the Feijão tailings dam

In a few days time it will be the first anniversary of the failure of the Feijão tailings dam at Brumadinho in Brazil. Last month the official expert panel released its report on the disaster – there is a website dedicated to the findings, which includes the full report in English and all of the appendices.

As expected, the report finds that the failure occurred as a result of static liquefaction. The investigation has deduced that failure initiated close to the crest of the dam but very rapidly progressed through the entire structure, allowing a comparatively shallow failure to develop. This was then followed by a series of retrogressive failures that released the large volume of mine waste.

There is a particularly interesting aspect of the report that will cause deep concern for those responsible for such structures:-

“The failure is also unique in that it occurred with no apparent signs of distress prior to failure. High quality video from a drone flown over Dam I only seven days prior to the failure also showed no signs of distress. The dam was extensively monitored using a combination of survey monuments along the crest of the dam, inclinometers to measure internal deformations, ground-based radar to monitor surface deformations of the face of the dam, and piezometers to measure changes in internal water levels, among other instruments. None of these methods detected any significant deformations or changes prior to failure.”

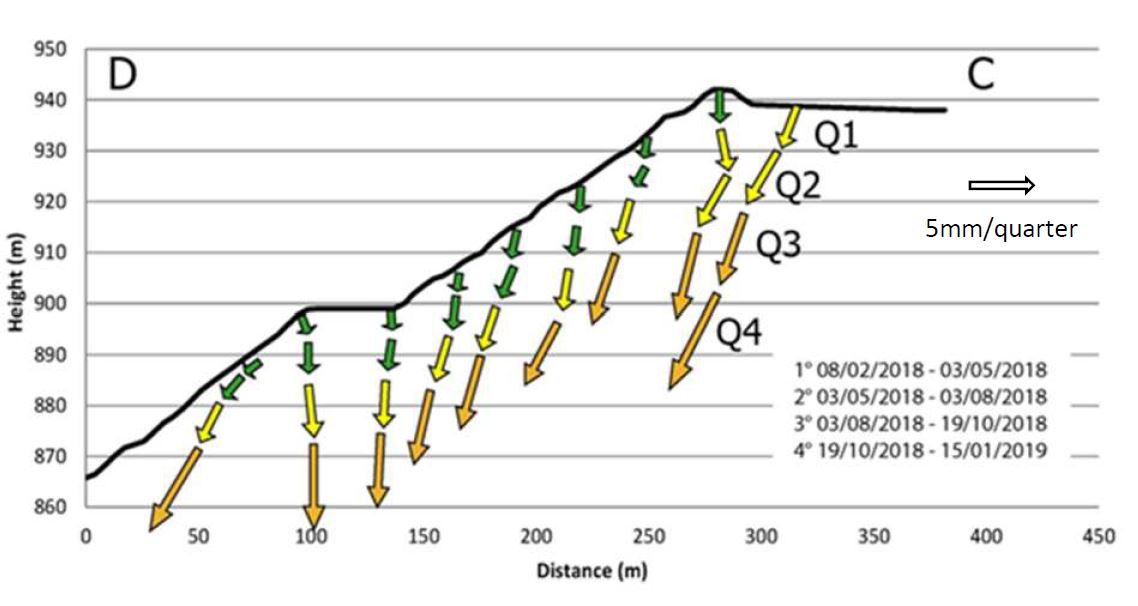

That such a catastrophic failure can develop with no signs of distress, and no indication that stability was being compromised, is a great surprise. It implies that the failure was extremely brittle. The Expert Panel looked in detail at all of the monitoring data, and undertook a back analysis of historical InSAR data. They conclude that the dam was settling at rates of up to 30 mm per year (as illustrated schematically in the image below), but this was expected and could not be used to infer that stability was compromised.

A schematic diagram showing the deformation of the Brumadinho dam in the year before failure, from the Expert Panel report.

.

In terms of the failure, the Expert Panel blames the upstream construction method deployed by Vale at Brumadinho. In particular, the Expert Panel is critical of the lack of effective drainage installed during the early phases of construction, which allowed very high pore water pressures to develop both during deposition (which meant that the tailings were loose) and then afterwards (which promoted failure). At the same time, the tailings contained a very high content of iron, which allowed them to become bonded, introducing the brittleness highlighted above. The upshot was that the dam was, in the words of the Expert Panel, “composed of mostly loose, saturated, heavy, and brittle tailings that had high shear stresses within the downstream slope, resulting in a marginally stable dam (i.e., close to failure in undrained conditions)”. In other words, Brumadinho was a disaster waiting to happen.

The final failure did not need a specific trigger – it was in essence progressive. Long term heavy rainfall had reduced suction forces whilst creep of the tailings caused strain to localise, which promoted creep rupture.

There are many lessons to learn from this failure, but absolutely critical will be the finding that failure could not have been anticipated through monitoring. This means that to understand the behaviour of the dam the local team needed a much more nuanced view of the properties of the tailings (and in particular their propensity to fail in a brittle manner) and the conditions within the dam. This is a critical lesson for the industry.

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.

Appendix D is rife with incomplete analysis and observances unrelated to a progressive monitoring practice. It is less than constructive to consider that you do not see “warnings” in the data, nor that in WHOLE all of the monitoring did not create a “picture” of activity, that was active over several years and that suggested not only localized effects but in total would create alarm that the structure was active and progressive. The presentation of the data in the report is less than complete, and in some cases suspect. It is clear than in any forensic study an outcome could be predetermined by knowing the initiation of, and the eventual result of all the operational and environmental actions that took place there over the years….if that was actually possible.

The operation of any site, no matter if a failure has occurred or not, is best managed by active monitoring. That monitoring needs to be transparent, always in 100% operational state, and the data disseminated across the operation and in the community. There is no DOWNSIDE to doing so. Presentation of monitoring data out of context of a daily review and dissemination is not reflective of a “working” Risk Reduction Monitoring operation.

The INDUSTRY failed again to realize this in the ICMM panel’s new STANDARD, for no apparent reason. David, I have a lot of respect for your work over the years and appreciate the awareness and opportunity created by your BLOG, insights, and efforts in tracking and informing us all about landslides and slope failures. In this case I would submit, that even freely available data, going back several years, highlights significant signals and precursors to change. The loss of traditional instruments from shear, disuse, or maintenance, lack of accumulated data results that are serial, and an ineffective and not well supported active monitoring practice created an opportunity where … as has been said now too many times… there were not indicators from instruments and data … that a progressive event was in hand.

Any tailings or containment structure is an active event. On my desktop right now, I can see active events at several TSF facilities across 4-5 countries. Simply selecting an Area of Interest (AOI) from nearly every major mine site will create a data source where displacements can be seen. Annual “seasonal” effects are easily noted as are diurnal patters in mass slope expansion and contraction. To imagine that any of these structures is static and not in a progressive state of change, even towards a designed equilibrium, is just not reality.

The content of the dam, it’s site perhaps ill-chosen, its operation managed but on a daily basis a combination of man, nature, and change — is at once volatile and can result, when any part of the balance is affected — in lasting change or initiation of effects that will “surface” perhaps well into the future. This is the premise of any initial, operational life considered, and in retirement analyzed risk evaluation and result.

It took more than a decade, during which MASSIVE slope failures occurred, ongoing fatalities resulted, and operational losses in the 100s of millions and more incurred — for active slope monitoring to become “necessary” for any well considered, professionally operated and managed mine. Now, dare to operate such a mine of scale from small to massive, without an active slope monitoring practice, protocol, and instrumentation that is not passive — it does happen, but it is a dying and uneconomic practice.

But for tailings, despite massive failures, loss of life, etc. the same tools, investment, and practices have not been utilized, is not considered a part of the tailings design and management, and has been in now major international “EXPERT” cases suggested was inconsequential and ineffective? This too is uneconomic, irresponsible, and will be noted in the coming months — a less than well informed outcome.

Each day I am asked about monitoring opportunities and the potential for success. Since 2006 each day I can tell you that if you monitor, you will see change. it may be change you are happy to see, or it may be change that leads to needed action, re-planning, re-engineering, but will be followed with re-SULTS.

In honor of all the lost life, potential, community pain, economic ruin, and environmental destruction, it is only one effort that can serve to put the future in a constructive context, and that is to establish pervasive monitoring and design, engineering, geological, and physical property considered Risk Reduction Monitoring at all mine operations globally. Use of technology does not guarantee results of any one flavor, but proper use, assessment, sharing, analysis, and dissemination of data results regularly changes an operation forever. I have been a part of these experiences, have witness many more, and see the data from 100s that considered valid and supported as such — has prevented, allowed to be managed, and assured of many assets the ability to operate, produce, and manage resources and assets under change, prefailure, and through failure in a constructive manner.

john