16 December 2013

The Rockville rockfall cliff has a history of dangerous collapses

Posted by Dave Petley

More information about the background to the Rockville rockfall

Over the weekend more information was released about the Rockville rockfall in Utah on Thursday, which killed two people. In some ways the most revealing information is summerised by the Salt Lake Tribune, which has a report about previous rockfalls on this set of bluffs. The report states that:

This is the sixth massive rockfall in the town of 251 since October 2001, when a sleeping resident narrowly escaped injury as a 300-ton boulder annihilated a third of his home. A year later, a car-sized boulder landed on Main Street. In spring 2007, a Main Street motorist collided with a fragment from a rockfall. And in November 2010, hundreds of rocks — the largest weighing 78 tons — crashed into the cliff base without hitting any property.

However, in February 2010 there was a very near miss, reporting that in February 2010 a 450 tonne block detached from the slope and fragmented. The report notes that:

Nobody was harmed, in large part thanks to a previously fallen boulder that it collided with at the base of the cliff. The biggest remaining fragment of the 450-ton rock was just 20 tons, but the pieces were moving fast enough that one rock crashed through one side of a washroom and out the other before damaging two vehicles.

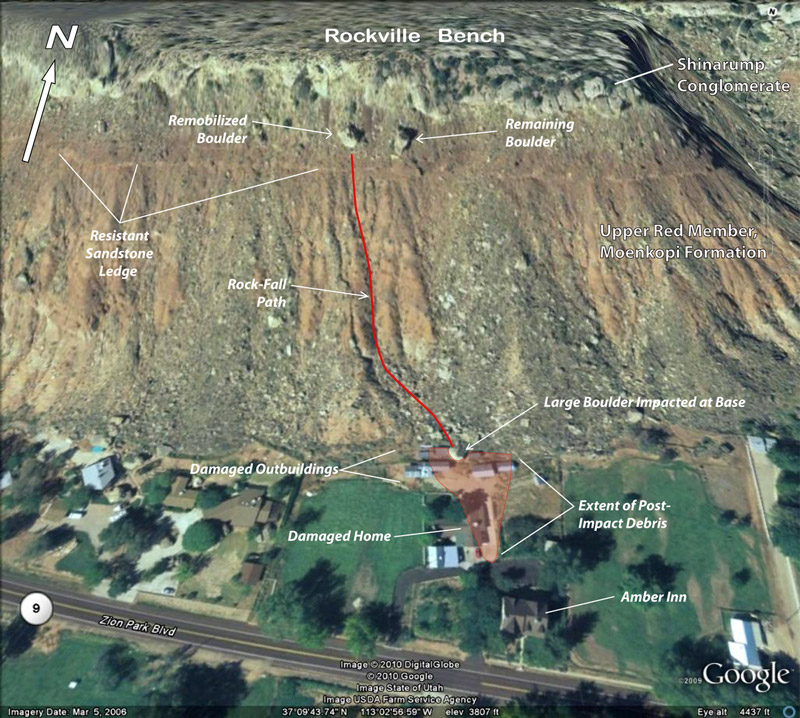

The Utah Geological Survey (UGS) report into the February 2010 event is available online. It includes some very good images of the aftermath of that rockfall, plus this annotated Google Earth image of the 2010 rockfall event:

..

Note that the house that was struck in the Rockville rockfall on Thursday is on the left side of the image. The UGS assessed the hazards associated with these cliffs in their report on the 2010 event (NB the document is a PDF). This is a very good review that I fully recommend you read. The key information in terms of future hazard is that the shadow angle (the angle from the top of the cliff that defines the maximum runout of the boulders) is 22 degrees. Thus, as the report states:

A 22° shadow angle from the base of the Shinarump cliff places many homes, roads, and other facilities in the northern part of Rockville within a high rock-fall-hazard area. Several structures south of the Virgin River on River Road (figure 2) may also be at risk from falling rock originating from the Shinarump-capped mesa to the south.

The report then makes a clear recommendation:

The UGS recommends further detailed investigation to evaluate the rock-fall hazard in Rockville; investigations should include a detailed assessment of potential sources (including bedrock and talus) and maximum runout distances (minimum shadow angle). Investigation results should include a map delineating areas susceptible to rock fall. Site-specific, rock-fall-hazard investigations should be performed by qualified geologic consultants for future development. Owners of existing homes within high rock-fall hazard areas should be informed of the hazard, and they may wish to retain a team of geologic and geotechnical consultants to investigate the risk from rock falls to their property and the feasibility of rock-fall risk-reduction measures.

The nature of the Rockville rockfall

The rockfall on Thursday appears to have been a large first time failure on the Shinarump Conglomerate that caps the slope, judging by this image from the Daily Mail:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2523559/Pictured-The-couple-crushed-inside-home-Utah-rock-slide.html

..

The detachment site is visible just above the tree, and the path of the boulders (of which just one struck the house) down the slope is clear. There may have been some entrainment of debris at the toe of the slope. The boulder that destroyed the house did not travel the longest distance.

Comparing the Rockville rockfall hazard approach with that of Christchurch, New Zealand

Finally, it is interesting to contrast the approach that adopted to manage this known hazard with that being adopted by Christchurch City Council in New Zealand in managing the rockfall hazards in the Port Hills area and the associated CERA reponses after rockfalls triggered by the recent earthquake sequence (see my gallery of images from these events here, here, here and here). In the Christchurch case, the Council and CERA are taking a very proactive approach to manage the hazard, based on a state of the art assessment of the level of hazard.

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.