1 April 2014

Scientists must use more jargon for public to appreciate science, study shows

Posted by Olivia Ambrogio

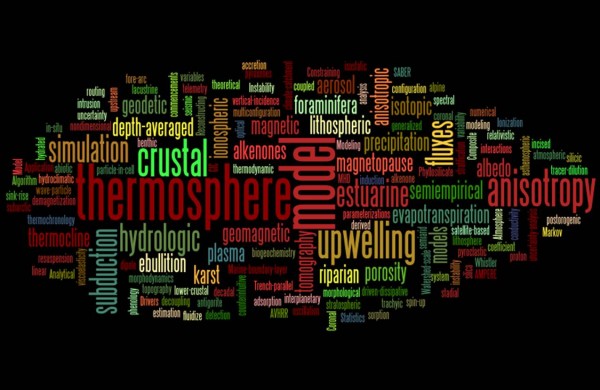

The title of this groundbreaking new study from the DULLNESS Center says it all. Image by Olivia Ambrogio, AGU.

By Abra Viligiomio

Most of the public is turned off by scientists’ overly accessible and personalized descriptions of their work, and scientists must try harder to interject long, technical phrases into their communications intended for the general public, new research shows.

“Almost 78 percent of those surveyed indicated they would be much more excited by science if it were explained to them in highly specialized language with a ‘just-the-facts’ approach,” said Bradley Oring, co-director of the Center for Delivering Unclear Language Lucidly, Nicely, Engagingly, Smoothly, and Succinctly (DULLNESS), which conducted the study.

“Scientists don’t seem to understand that the public doesn’t want them to sound like people, with likes and dislikes and questions that interest them—they want them to sound like scientists,” Oring said. That means fewer stories about the people behind the experiments, fewer analogies, and much more jargon.

The results of the study reflect what many professional science communicators already know. Science journalist Ernest Worthing with National Geomorphology magazine says the study didn’t surprise him.

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve wished that researchers would stop explaining why their work is so cool and exciting,” he said. “Instead, mention your use of Fourier transforms, if your work involves them. Readers love hearing about those kinds of details.”

Natalia Otrue, a reporter for Popular Schematics magazine, says she’s experienced the same frustrations when trying to get good quotes from scientists. The scientists, she said, all too often go beyond describing data and instead tell the “so what” story.

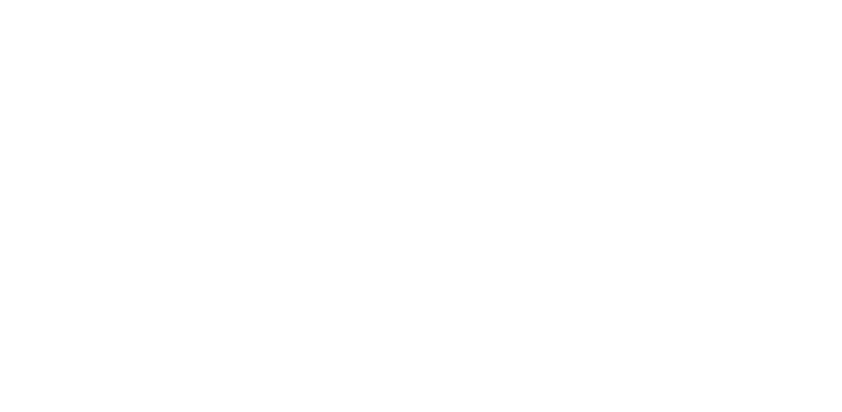

When trying to captivate the public, consider using words like “anisotropy” to really get people’s attention. Study the word cloud above for more great jargon to slip into everyday conversations. Wordle by Olivia Ambrogio, AGU.

“Where’s the mystery in telling us what’s new about your results? Why can’t you just let folks figure it out for themselves for once?” Otrue asked. “The best interviews are ones when scientists spend a half hour providing background on other people’s work, and don’t point out what’s new with their research.”

The same applies to scientists working with policy makers, according to the DULLNESS Center. Study participants who work on policy issues that intersect with scientific research said that the major obstacle to working with scientists is the scientists’ tendency to discuss the big-picture implications of their research.

“It’s better to just dive into the details,” Capitol Hill staffer Justin Case said.

“Let’s face it—when writing a memo to my boss about particle colliders, I can’t tell you how much it helps to have a 400-page report on the topic. A one-page summary would just muddy the waters,” Case said.

Case’s colleague Renata Ideas agreed. She said she gives scientists visiting Capitol Hill the following advice: “Remind us how smart you are—use five-syllable words, or better yet, Latin.”

And don’t discount the importance of good leave-behind materials, Ideas added.

“After all, a picture is worth a thousand words. And by ’picture,’ I mean graph or chart. By including as many graphs as possible in your leave-behinds, you’ll ensure your message is understood. There’s nothing like a histogram to nail home your point.”

In the end, Oring hopes that the study will serve as a wake-up call to scientists everywhere. With just a little more effort, he said, they can eliminate all personality and resonance from descriptions of their work.

“If scientists plan their school visits, public talks, policy meetings, and interviews in advance to include lots of experimental details and as much technical language as possible, they’re sure to win the public’s interest and trust,” Oring said.

– April Fools! In case you can’t tell, the story above is an April Fool’s Day post. If you are a scientist or science communicator, please don’t follow Oring’s advice, which (along with his study, the DULLNESS Center, and all the people quoted above) was invented by a manic but well-meaning AGU staff member, Olivia Ambrogio. The quotes for this piece were developed with the help of science reporters Dan Vergano and Alexandra Witze, AGU Public Affairs specialists Erik Hankin and Nick Saab, AGU Public Affairs intern Kathleen Compton, and other contributors familiar with scientists communicating with general audiences.

Whatever you do, don’t post comments about other ways that scientists should not follow Oring’s advice.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.

You all rock — thanks for this! Happy April 1 to you all

@ Jana Goldman, et al., my sediments exactly.

As a science writer, this really made my day. 🙂 Kudos to Olivia and the other contributors!

Okay. Very funny!

Fabulous!

Thanks so much for all of your comments. We had a fun time writing the piece, and I’m so pleased you’ve enjoyed it.