6 January 2012

Friday fold: the Contorted Bed

Posted by Callan Bentley

I’ve got lots of cool stuff to share with you from my South Africa trip, but one of the most geologically interesting was the very last thing I did on the trip. Lily and I got back to Johannesburg, and I read had just picked up a copy of Geological Journeys: A traveller’s [sic] guide to South Africa’s rocks and landforms by Nick Norman and Gavin Whitfield. In it, I learned that a really cool outcrop was located only a few kilometers away from our hotel, so the morning of our last day in the country, my wife and I walked over there and checked it out.

The rock unit in question is “the Contorted Bed,” a folded banded iron formation unit that is part of the lower Witwatersrand Supergroup. The Witwatersrand Supergroup is a fascinating package of sedimentary rocks. In its upper portion (the Central Rand Group), it has five major layers of conglomerate which are highly auriferous, or gold-bearing. These are Archean-aged placer deposits (fluvial sorting of dense gold nuggets and sand into high concentrations). The quartz-rich coarser grained strata make ridges that poke up above the land; these are the source of the Supergroup’s name: “Witwatersrand” means ‘ridge of white waters,’ named for the waterfalls that once poured off these ridges. (And by the way, “W” is pronounced as a “V” in Afrikaans.) The association of these ridges with the gold deposits is memorialized in the contemporary use of the word “rand” for the currency of South Africa.

The ancient placer “reefs” of the Wits are extraordinary. They were first mined in 1887, and since then they have produced more than 50,000 tons of gold. That is about half of all the gold ever mined anywhere on the entire planet Earth. Production has declined in recent years to merely ~400 tons/year, about 15% of the world’s total. It’s going to continue dropping too, as all the easy-to-reach gold has been captured, and even the massive waste piles have been re-processed through several generations of improved extraction techniques (like cyanide heap-leaching). These tailings are very distinctive deposits in town, and their anthopogenic geometries stand out as one flies into Jo’burg. Here’s two shots of them that I shot out the airplane window a few days ago as we flew back from Cape Town:

Lower in the Witwatersrand, in the non-auriferous basal units, lies the subject of today’s post, the Contorted Bed. This peculiar banded iron formation lies within the Parktown Shale, which overlies the Orange Grove Quartzite, the very bottom-most of the Wits units. The banded iron formation is distinct on several levels: it’s BIF rather than clastic sediment (though it’s got a much higher shale component than the BIFs I’ve seen in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota), it’s intensely folded in a way that the overlying and underlying quartzites are not (and the shales are presumably just cleaved), and it’s basin-wide in extent. All of these means it’s a superb marker bed for figuring out one’s stratigraphic position within the Wits Supergroup.

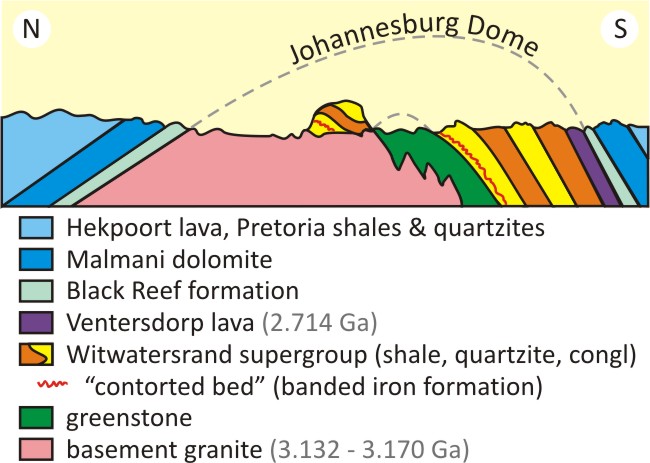

Overall, Johannesburg is sited on a structural dome, with the Witwatersrand strata mainly dipping off to the south (and thus mainly exhibiting east-west strikes). In cross-section, that would look something like this:

The outcrop is exceptionally convenient for visitors to Jo’burg. It’s located on both sides of Jan Smuts Avenue, just east of the University of Witwatersrand.

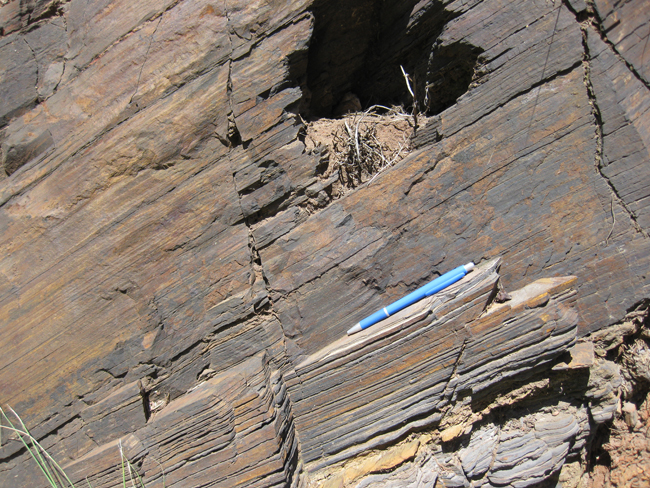

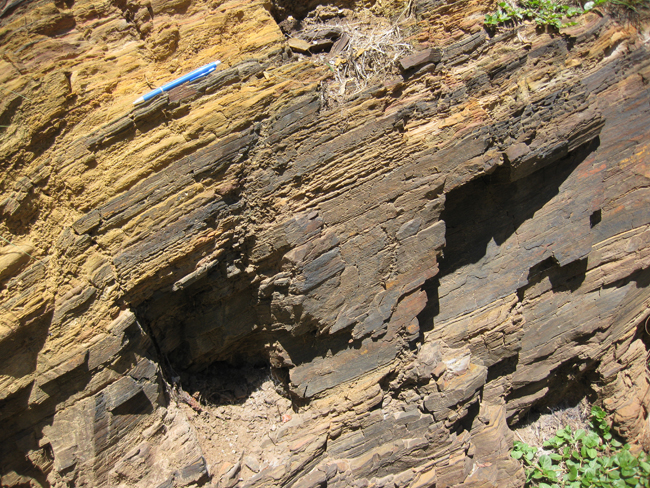

Here are some looks at the outcrop, starting with the shale (slate) above and below the BIF:

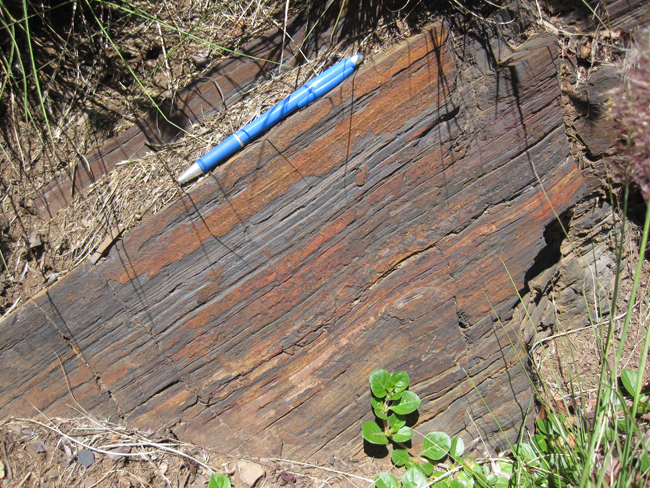

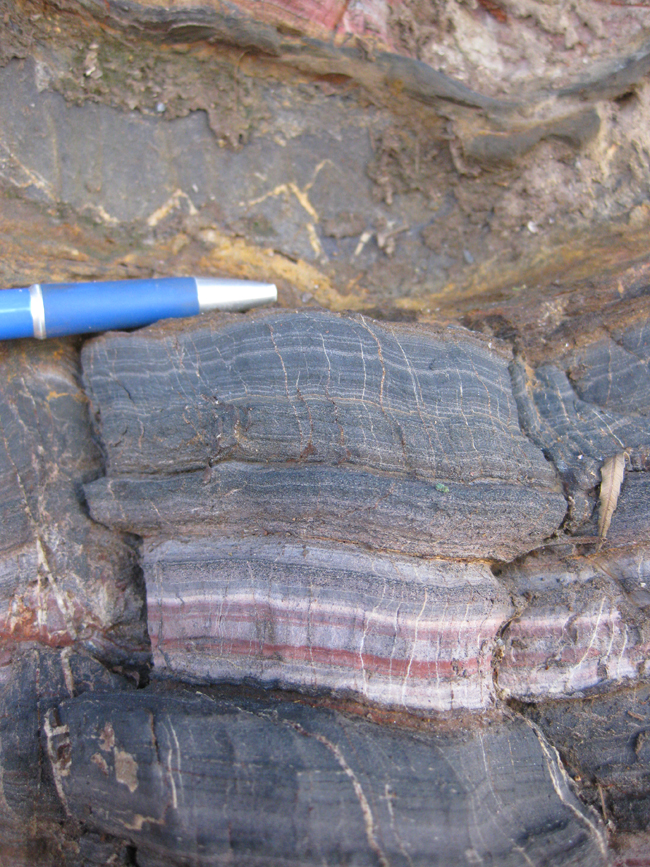

Here’s some shaly BIF. It’s magnetic:

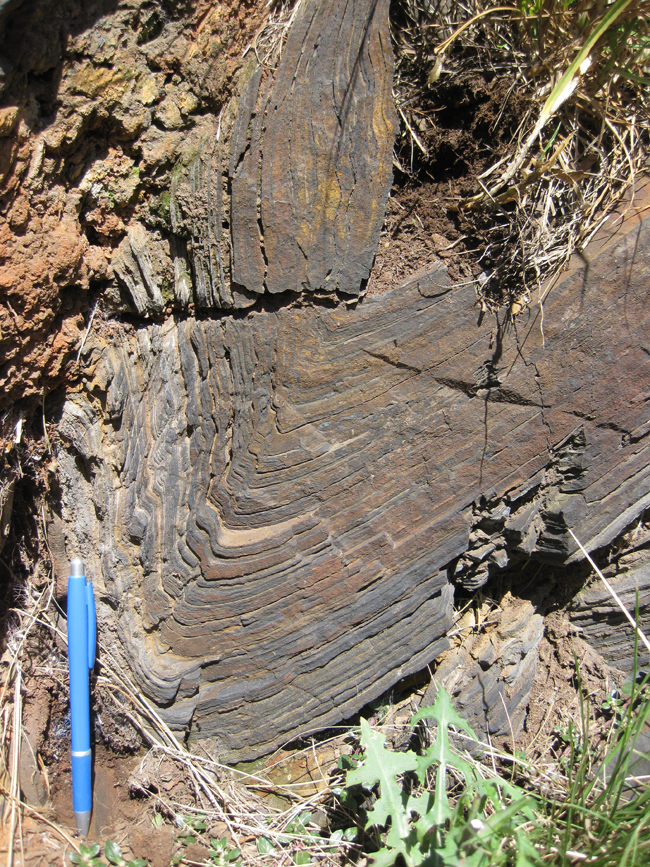

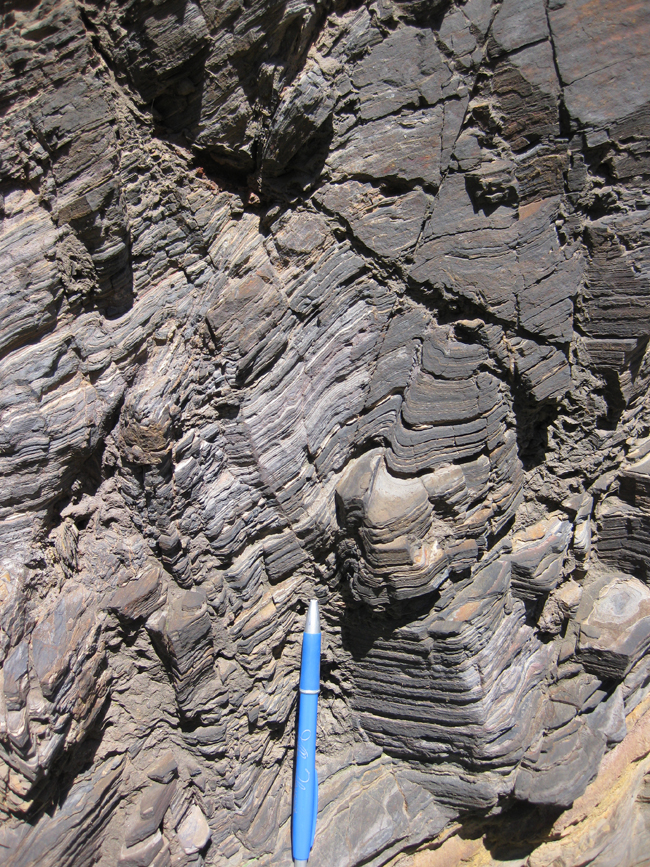

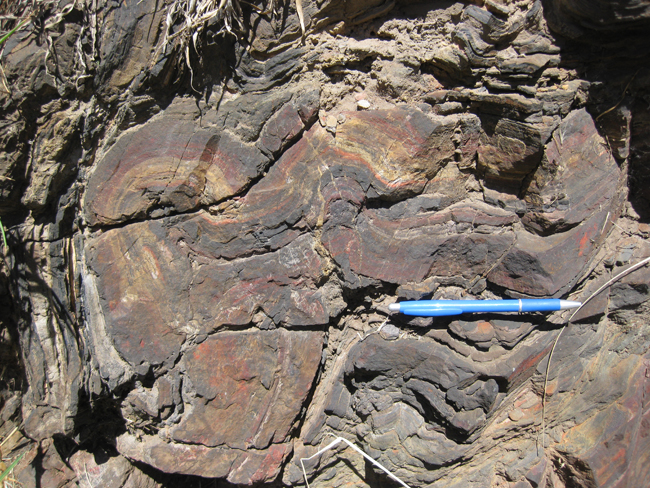

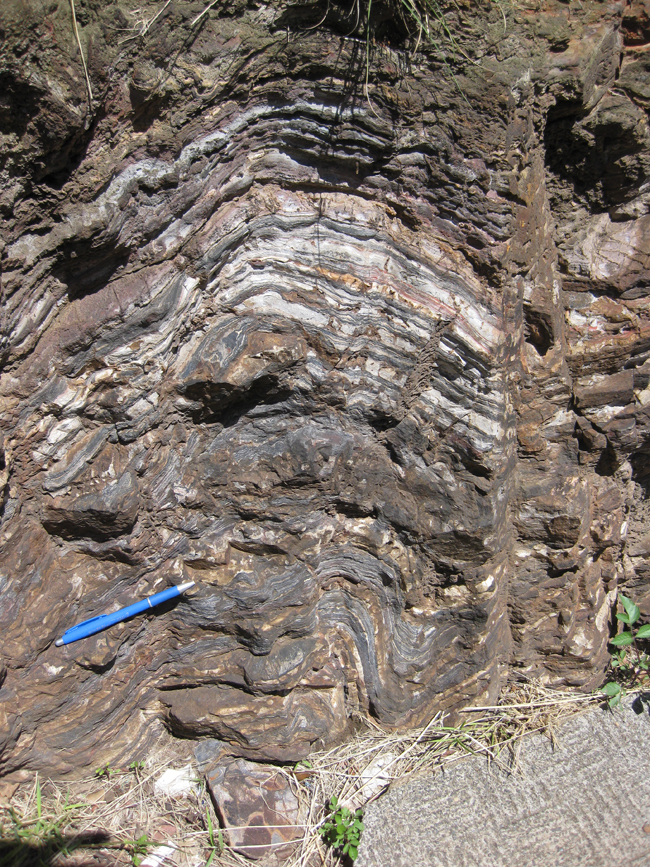

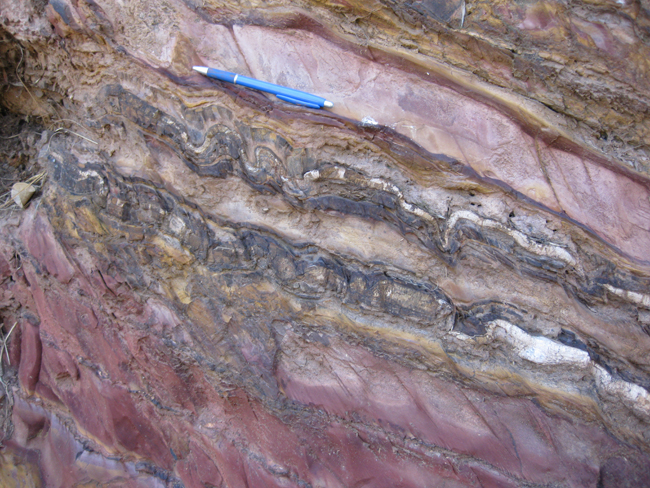

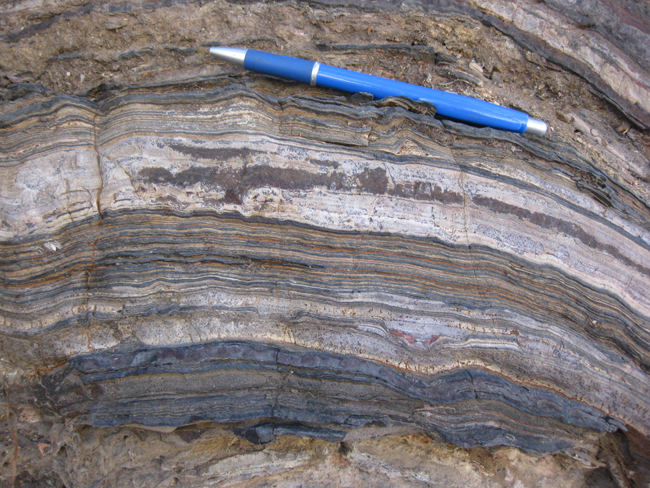

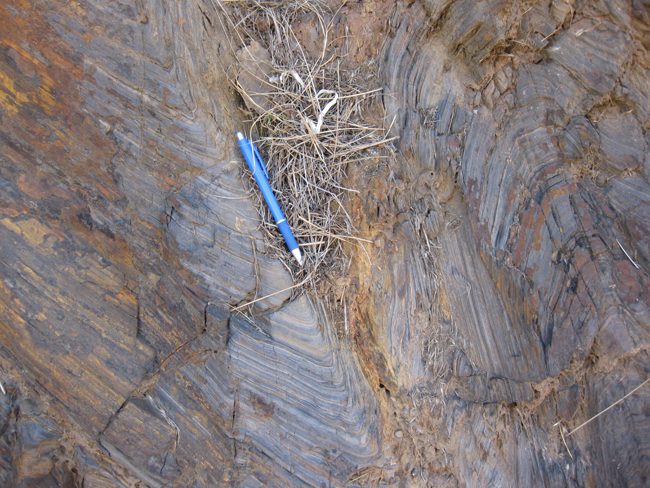

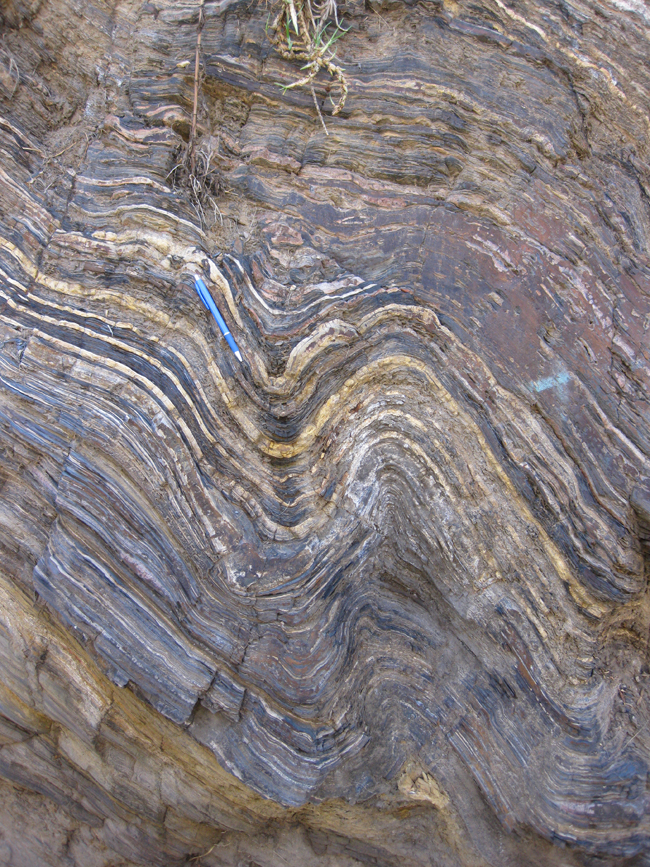

And here it is folded:

Here’s a nice basketball-sized sample lying in the dirt. Lily wouldn’t let me bring it home:

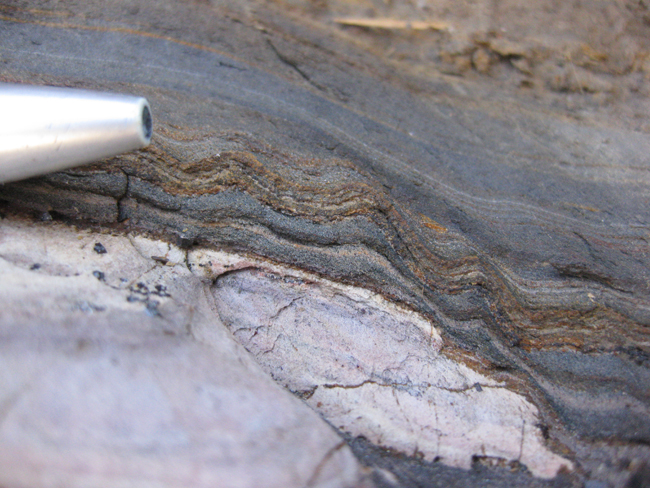

Some interesting “sheathiness” in this one…

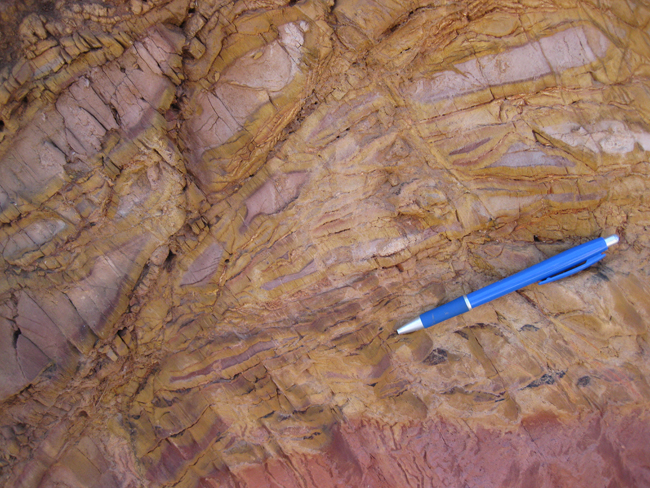

Liesegang banding staining rosy shale:

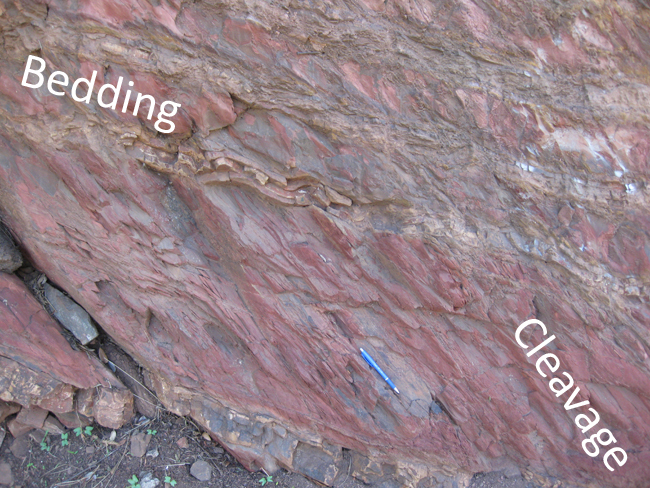

More bedding/cleavage relationships in the shaly strata:

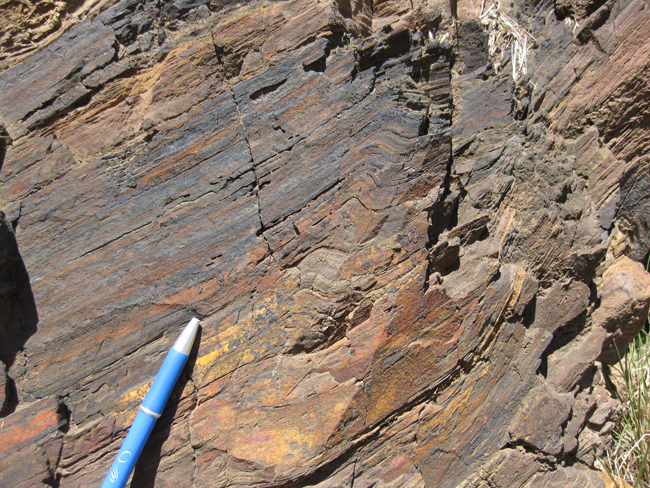

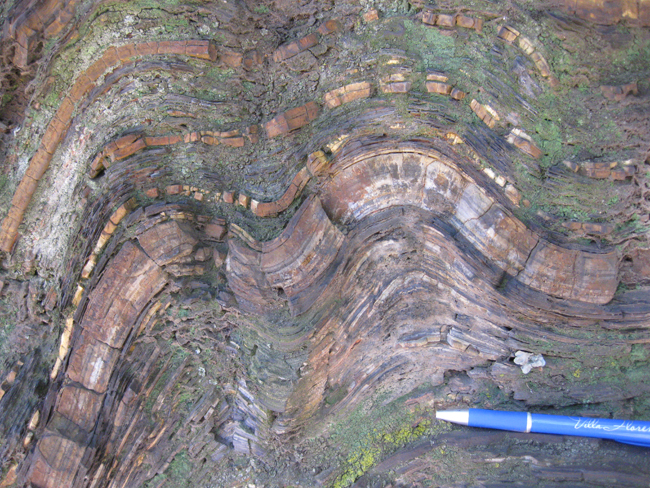

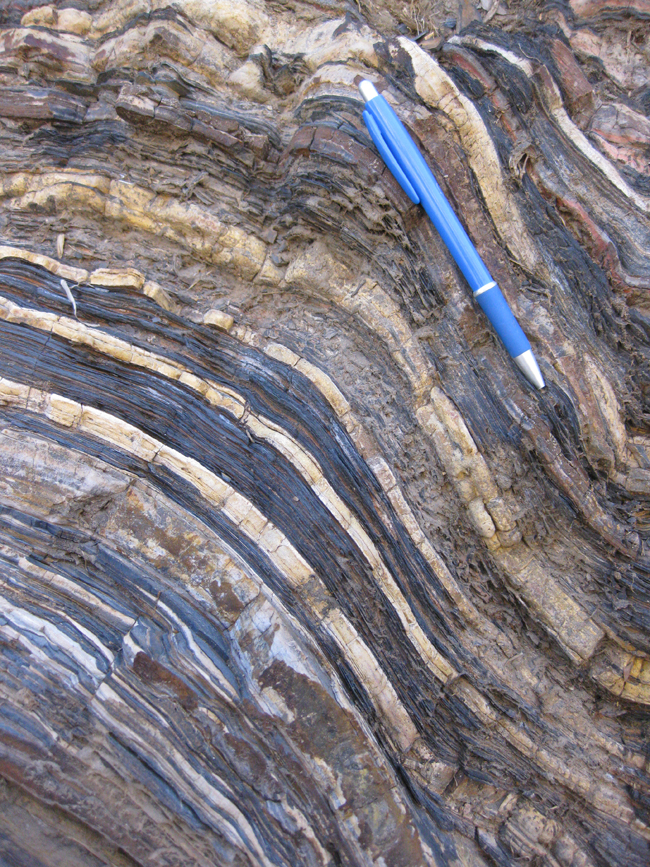

Different strain responses in layers exhibiting differing composition:

Small extensional veins perpendicular to bedding in the next two:

People with folded BIF:

Now, that’s a contorted bed!

Very small scale folds hidden in that last one. Let’s zoom in to see them:

A feast for the eyes, these rocks. I’m so glad I got to see them in person.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Insanely cool. Very beautiful outcrop.

Did you come across any stromatolites in this formation?

Not in this formation – but I did see them in the Malmani dolomite (a formation you can see in the cross-section near the top of the post).

Do you have any pictures of that?

I do – all in good time, dear Jan!

In the meantime, you can enjoy these classic giant stromatolites from Chris Rowan’s blog.

The ones I saw are from the same formation – the Malmani dolomite.

OMG Those are AMAZING!!! Thanks for that link! Look forward to your pics 😀

Here’s a link to the Malmani stromatolites I saw, by the way:

https://blogs.agu.org/mountainbeltway/2012/01/24/paleoproterozoic-stromatolites-from-the-malmani-dolomite/

wow…they are amazing!

Hey Callan – great photos! really enjoying your SA posts. I haven’t seen this awesome outcrop. Is this soft sediment deformation? I’ve seen similar structures in the Red Lake Belt BIFs in Ontario… also with tiny flame structures. Did you see any flame structures by any chance?

I did not see any flame structures there… And the combination of well-developed foliation in the shale / slate that is axial planar to the folds suggests to me that this deformation is at least partially tectonic in origin.

I totally agree

[…] year for me and the world’s Archean banded iron formations. Between Soudan, Minnesota, and the Witwatersrand’s “Contorted Bed”, you might say that I’ve become BFFs with the […]

[…] let’s zoom in on a little something I saw at the outcrop of the Contorted Bed in downtown Johannesburg, South […]

Our lab just imaged a small fold from this site (brought back home, sliced, diced, ground, and polished) in this macro GigaPan, if you’d like to explore it a bit for yourself:

http://www.gigapan.com/gigapans/146652

I love it. I had exactly the same experience on my last two days in Johannesburg. I was just there in January 2019, and I think the football sized piece was still there. I too thought about bringing it home but then visualized United Airlines and the excess baggage scale. I love your diagrams with explanations.