16 September 2010

Drilling: what, why, and how

Posted by Callan Bentley

As mentioned, I spent a significant part of last weekend was spent on a paleomagnetic sampling project with collaborators from the University of Michigan. On Friday, this was our field area:

That’s the south slopes of Old Rag Mountain, a popular Blue Ridge hiking destination because unlike many Virginia peaks, when you get to the top, you see some rocks instead of 100% trees:

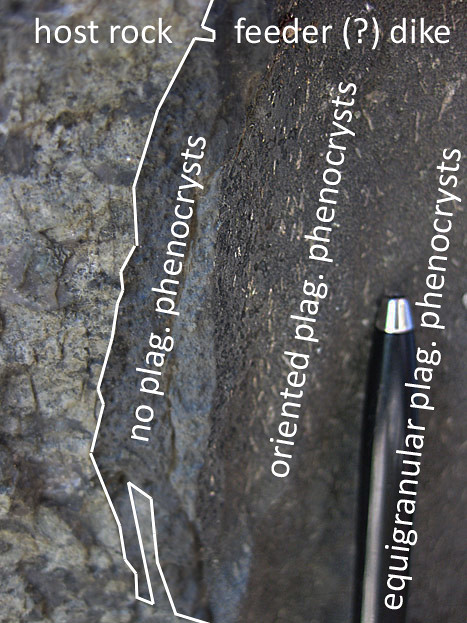

But we didn’t come here for the view. We came here for the dikes. Here’s the edge of one, with a pen for scale:

These are dikes of basalt and meta-basalt of the Catoctin Formation which are presumed to be feeder dikes pumping mafic lava to the surface of Virginia around 570 million years ago, during the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia and the opening of the Iapetan Ocean basin. The dikes cut across the Grenville-aged basement rocks, in this case the Old Rag Granite of about 1000 million years age. The Old Rag area is especially great because the dikes are less metamorphosed than they are in other parts of the Blue Ridge province, where the Catoctin has been cooked into greenstone. Here’s an annotated view of the previous photograph:

As far as this project goes, we are interested in these dikes for the information that they (potentially) contain about the orientation of the Earth’s magnetic field in Virginia at the time of the supercontinent Rodinia’s breakup. By sampling these dikes and then analyzing the samples at their paleomagnetism lab back in Ann Arbor, Fatim and Matt hope to put some constraints on the question of paleo-Virginia’s latitude when these dikes cooled into solid rock.

As a reminder, you are not allowed to sample any rocks in any national park unless you have first applied for and been granted a research sampling permit by the National Park Service.

Close to the planet’s surface, the Earth’s magnetic field is shaped like a torus (or, in less technical terms, a doughnut, but one of those donuts with a pinched up midsection, and more of a dimple than a hole). It exits at the south magnetic pole, wraps north around the Earth, and plunges back into the inner core at the north magnetic pole:

A magnetically-sensitive mineral forming in a modern rock would have an upward-oriented high-angle magnetism if it formed at high southerly latitudes, a moderate-angled upward orientation at moderate southerly latitudes, a horizontal, northward-pointing orientation at the magnetic equator, and then the reverse as you head towards the north pole: a moderate-angled downward orientation at moderate northerly latitudes, and a downward-oriented high-angle orientation if it formed at high northerly latitudes, just like the red arrows show in the above image.

Of course, the flow of the magnetic field occasionally reverses direction (emerging at the north magnetic pole instead, and flowing south), but the shape of the field doesn’t change:

So the angle of inclination of a fossil magnet should be the same regardless of whether it’s poking up or plunging down, relative to the surface of the Earth. In this way, paleomagnetism can reveal the approximate latitude (but not longitude) at which a rock formed.

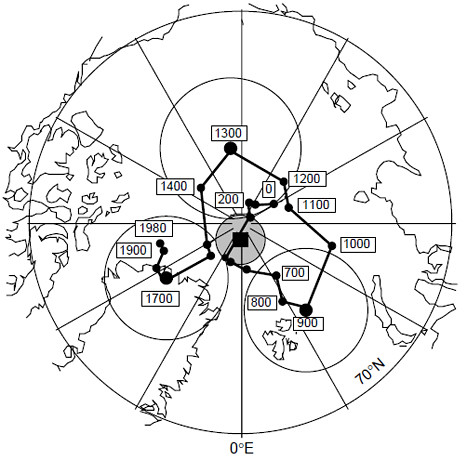

But wait, is it really so simple? No, of course not. Check out the map below, showing the positions of the north geomagnetic pole over the past 2000 years, with numbers showing the position of the pole in a specific year CE. It moves! The circles around geomagnetic poles at 900, 1300, and 1700 CE are 95% confidence limits on those geomagnetic poles; the mean geomagnetic pole position over the past 2000 yr is shown by the square with stippled region of 95% confidence. These data were compiled by Merrill and McElhinny (1983) and plotted by Butler (1982).

So this map shows us that even though the magnetic pole does wander about a bit, 2000 years of data is enough to generate an average which is more or less coincident with the geographic pole. And therefore a statistically significant batch of data (spread over a 2000-year-or-greater spread of time) will also reflect that average pole position.

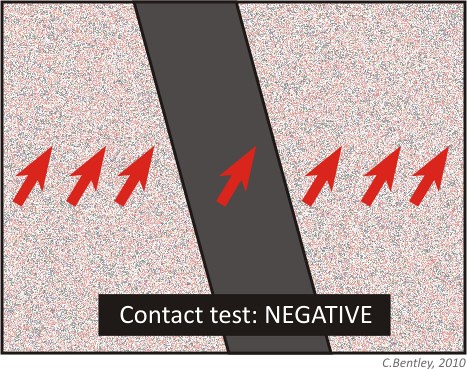

Meert, Van der Voo, and Payne (1994) made a first attempt at constraining the paleomagnetics of the Catoctin Formation. Four of their 32 sites were feeder dikes, sills, and host rock (Grenvillian basement complex). One of the things these authors did was that they performed a “contact test” on two of their dikes. A contact test is a way of using an igneous contact (as with a dike) to determine whether the whole region has been magnetically reset, perhaps by thermal activity accompanying contact metamorphism. Consider this situation:

You sample a dike and its surrounding host rock, at several distances away from the dike. You find that they all give you the same magnetic orientation. This suggests you have the magnetic signature of a later overprinting, not the original orientations of dike and host rock.

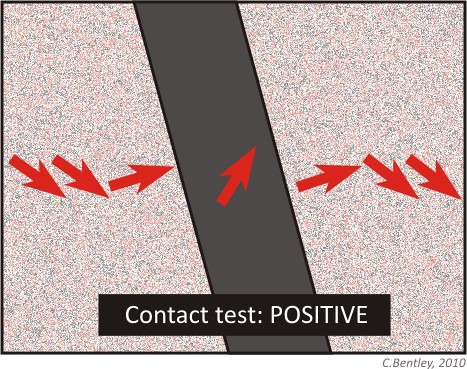

Now what if you found this, instead?

Here, your dike shows a distinct signature that is different from the host rock, and the host rock shows a uniform orientation except right next to the dike, where the heat of the intrusion has partially reset the (older) host rock’s magnetism. If I were to annotate this up (with color coding!), it would look something like this:

Passing the contact test is critical to tying the two rocks’ magnetic data to their age data. It’s only with a positive contact test that you can use this data to say anything about where Virginia (and thus ancestral North America, often dubbed “Laurentia”) was when the Catoctin dikes were intruded.

The contact test is something that our team wanted to repeat, with more dikes than just the two that were featured in the Meert, et al. (1994) paper. We also wanted to double-check their results, and verify, reject, or modify them as our data warranted.

The key to constraining the magnetic orientation of these rocks as precisely as possible is to constrain the current orientation of the samples as precisely as possible. We measured the strike and dip of the surface of each sample very carefully, before we extracted it from the bedrock. At Old Rag Mountain, we were not allowed to drill (Old Rag is a wilderness area with no motorized equipment allowed), so we were collecting oriented hand samples.

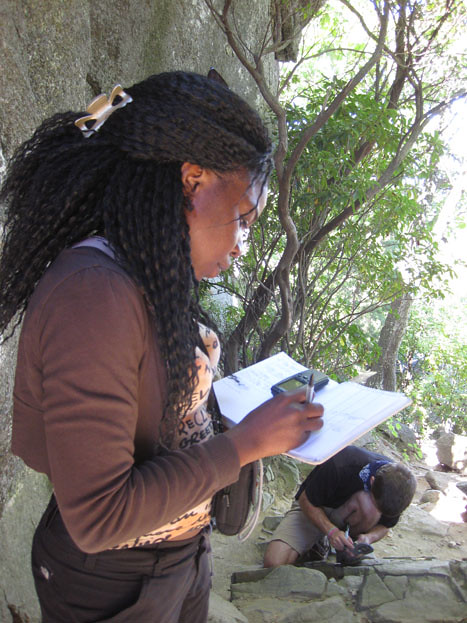

Here’s Fatim Hankard writing orientation data in her field notebook while Matt Domeier takes a strike and dip reading in the background, using his Brunton compass:

Because these rocks are inherently magnetic (that’s why we’re sampling them, after all!), we have to control for the possibility that the rocks themselves might be throwing off our Brunton compass needles. A second compass is employed to control for any magnetic field coming off the rocks themselves. This is a solar compass. If you know exactly where you are (note Fatim’s GPS unit in the above photo), and when you are taking the measurement, you can use this solar compass to double-check the orientation you get from the Brunton compass.

Here’s Matt’s solar compass butted up against one of our Old Rag samples. Note the shadow being cast by the compass’s nomen, and also note the “arrow with a prong” strike and dip symbol that we wrote directly onto the face of the sample with a Sharpie:

Next, take a look at a photo of a sample once extracted. We label it redundantly, not only in terms of the orientation lines, but also in terms of the sample’s identity. That way, we’re less like to find a bunch of scratched-up but un-identified and un-orientable rock samples once the van gets back to Michigan:

While poking around, I found this interesting feature at the edge of one of the dikes. I’m hoping one of my more petrologically-inclined readers may be able to offer me some kind of interpretation of this pattern:

What I noticed is that in the first few mm of the dike, right up against the contact with the host rock, there are no white lathes of plagioclase feldspar. These relatively large feldspar crystals are phenocrysts, big chunky crystals that grow in the magma when it’s cooling relatively slowly underground, but then entrained in the flow as it moves upwards into the dikes, whereupon the surrounding liquid chills rapidly to make fine-grained basalt. So there are no phenocrysts right at the edge of the dike, then there are a bunch, all aligned with one another (but with no preferred sense of imbrication, so far as I can tell), and then there are more phenocrysts in the bulk of the dike, but they are (a) less concentrated, and (b) lack any preferred orientation. Let me annotate it for you, then go back and take another look at the unannotated version, so you can see what I’m referring to:

Okay, petrologists, I want to hear from you: How should I interpret this?

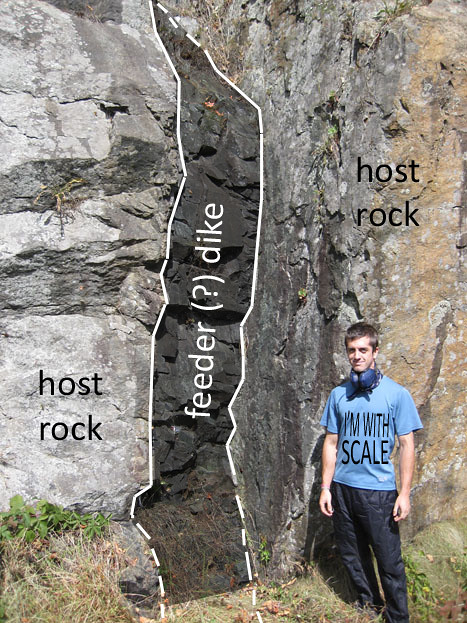

Back to the paleomag… On Saturday, we went to another location to sample. This one was much more convenient because (a) it was right on the side of the road, and (b) it wasn’t a wilderness area, so drilling was allowed. This was at the lovely selection of Catoctin dikes downhill (north) from the Little Devils Staircase overlook, on Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park. Here’s a charismatic dike with Matt acting as a sense of scale:

Annotated:

We unpacked the gasoline-powered diamond-grit-tipped drills and hooked them up to the water pump. We put on ear- and eye-protection, and got to work:

One the sample has been drilled out, you’re left with an empty hole. The white liquid is the cooling water with suspended dust from the abraded rock. This hole is about 3 cm in diameter:

The core (2.5 cm diameter) that came out of that hole:

In our field area, a core this size of the dike rock takes about ten minutes to extract. Basement rock (host rock) takes longer, as it’s made of harder minerals.

One worry is that the core will snap loose while you are drilling it out. If this happens, it may start rotating in the hole, and you will lose all sense of how it was originally oriented, which means you’ve just wasted a lot of time for no gain in data. To protect against this possibility, we used a technique of scoring a second circle with the drill bit, partially overlapping our actual core like a Venn diagram:

This way, if the core snaps off, you can line up its arc with the rest of the circle inscribed on the outcrop next to the hole. Whew! Core saved!

Fatim extracting another core:

After the core is drilled out (but still in its hole), Fatim oriented it. Notice the new array here – it’s a stand with slots into the drill-hole, then has a Brunton compass atop it with a solar compass atop that:

As you can see with this example, the solar compass is just about to become useless as the afternoon shadows advance! Next up, record all the orientation information (trend and plunge of the cylinder’s axis), and then score the core with a line:

Fatim and Matt sampled for two more days after I had to leave them due to other obligations, like teaching. They are headed back to Michigan today. Soon, hopefully, we’ll see whether our sampling campaign yields any meaningful results… Stay tuned!

As a final note, I would like to point out that this collaboration was born when Fatim read my blog post on feeder dikes and then proposed that we combine her paleomag skillz with my dike-location knowledge. It’s not the first time that my blogging has yielded a great opportunity, but it seems to be a shining example of how virtual connections online can lead to tangible work in the real world. The blog-curious should take note.

_______________________________________

References cited:

R.F. Butler. PALEOMAGNETISM: Magnetic Domains to Geologic Terranes. Originally published by Blackwell in 1984, 248 pp. Updated online 2004. Retrieved September 15, 2010, from http://www.pmc.ucsc.edu/~njarboe/pmagresource/ButlerPaleomagnetismBook.pdf.

J. G. Meert, R. Van der Voo, and T.W. Payne. “Paleomagnetism of the Catoctin volcanic province: A new Vendian-Cambrian apparent polar wander path for North America,” March 10, 1994. Journal of Geophysical Research 99, No. B3, pp. 4625-4641.

R. T. Merrill and M. W. McElhinny, The Earth’s Magnetic Field, Academic Press, London, 401 pp., 1983.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

As I’m still a 3rd year student I might be horribly wrong, but I’ve got a hypothesis about the orientation of the plagioclase phenocrysts:

When the magma intrudes the host rock and continues flowing, strong shear occurs near the borders of the dike while less shear occurs towards the middle. This shear causes elongated crystals (like the plagioclase) to align parallel to the flow plane. As the magma solidifies inwards, the crystals’ orientation gets recorded in the rock. If this dike started solidifying during rapid flow and then suddenly stopped flowing, the crystals at the border got captured with a common orientation, while the crystals lose their common orientation towards the middle of the dike (since no flow = random orientation). Perhaps an extremely simplified picture can clarify my gibberish:

{{ ^ ^ Flow ^ ^ }}

H }} || || {{ R

O {{ | | / – \ / | – /|| }} O

S }} || \ / | – \ \ || {{ C

T {{ || / – \ / | – / / | }} K

}} | / \ | / – \ – \ || {{

{{ || || }}

In this picture the | \ – etc. are the aligned crystals, which share a common orientation at the edges of the dike and total randomness in the middle.

… my beautiful picture got messed up since double (and more) spaces got cut out :-/

Sorry folks, you must rely on your own imagination now

Right — that makes sense to me, diagram notwithstanding — 🙂

So I get why the lathes are aligned versus not aligned in the two inner areas I labeled. But…

The thing is, why are there NO plag. lathes immediately next to the contact? Does this represent a chilled margin before the phenocryst-rich magma squirted into the dike?

Right — that makes sense to me, diagram notwithstanding — 🙂

So I get why the lathes are aligned versus not aligned in the two inner areas I labeled. But…

The thing is, why are there NO plag. lathes immediately next to the contact? Does this represent a chilled margin before the phenocryst-rich magma squirted into the dike?

Right — that makes sense to me, diagram notwithstanding — 🙂

So I get why the lathes are aligned versus not aligned in the two inner areas I labeled. But…

The thing is, why are there NO plag. lathes immediately next to the contact? Does this represent a chilled margin before the phenocryst-rich magma squirted into the dike?

Right — that makes sense to me, diagram notwithstanding — 🙂

So I get why the lathes are aligned versus not aligned in the two inner areas I labeled. But…

The thing is, why are there NO plag. lathes immediately next to the contact? Does this represent a chilled margin before the phenocryst-rich magma squirted into the dike?

Right — that makes sense to me, diagram notwithstanding — 🙂

So I get why the lathes are aligned versus not aligned in the two inner areas I labeled. But…

The thing is, why are there NO plag. lathes immediately next to the contact? Does this represent a chilled margin before the phenocryst-rich magma squirted into the dike?

Right — that makes sense to me, diagram notwithstanding — 🙂

So I get why the lathes are aligned versus not aligned in the two inner areas I labeled. But…

The thing is, why are there NO plag. lathes immediately next to the contact? Does this represent a chilled margin before the phenocryst-rich magma squirted into the dike?

I’m leaning towards a chilled margin for the no plag section, but part of me just spent 15 minutes paging through Passchier & Trouw’s vein section thinking about relative timing of the magma injection. Maybe the first magma that intruded in was plagioclase poor. When the fault (because we’re probably talking about basaltic magma coming in along a fault) continued to grow, it split the new basalt dike instead of breaking along one of the basalt-country rock boundaries. The next magma to intrude had plagioclase laths and they ended up being flow-banded near the edges, but not in the middle. This could use a diagram or two…

I like it — that was my gut reaction to this sight, but I’m pleased to hear you say it!

I’m leaning towards a chilled margin for the no plag section, but part of me just spent 15 minutes paging through Passchier & Trouw’s vein section thinking about relative timing of the magma injection. Maybe the first magma that intruded in was plagioclase poor. When the fault (because we’re probably talking about basaltic magma coming in along a fault) continued to grow, it split the new basalt dike instead of breaking along one of the basalt-country rock boundaries. The next magma to intrude had plagioclase laths and they ended up being flow-banded near the edges, but not in the middle. This could use a diagram or two…

I like it — that was my gut reaction to this sight, but I’m pleased to hear you say it!

I’m leaning towards a chilled margin for the no plag section, but part of me just spent 15 minutes paging through Passchier & Trouw’s vein section thinking about relative timing of the magma injection. Maybe the first magma that intruded in was plagioclase poor. When the fault (because we’re probably talking about basaltic magma coming in along a fault) continued to grow, it split the new basalt dike instead of breaking along one of the basalt-country rock boundaries. The next magma to intrude had plagioclase laths and they ended up being flow-banded near the edges, but not in the middle. This could use a diagram or two…

I like it — that was my gut reaction to this sight, but I’m pleased to hear you say it!

I’m leaning towards a chilled margin for the no plag section, but part of me just spent 15 minutes paging through Passchier & Trouw’s vein section thinking about relative timing of the magma injection. Maybe the first magma that intruded in was plagioclase poor. When the fault (because we’re probably talking about basaltic magma coming in along a fault) continued to grow, it split the new basalt dike instead of breaking along one of the basalt-country rock boundaries. The next magma to intrude had plagioclase laths and they ended up being flow-banded near the edges, but not in the middle. This could use a diagram or two…

I like it — that was my gut reaction to this sight, but I’m pleased to hear you say it!

I’m leaning towards a chilled margin for the no plag section, but part of me just spent 15 minutes paging through Passchier & Trouw’s vein section thinking about relative timing of the magma injection. Maybe the first magma that intruded in was plagioclase poor. When the fault (because we’re probably talking about basaltic magma coming in along a fault) continued to grow, it split the new basalt dike instead of breaking along one of the basalt-country rock boundaries. The next magma to intrude had plagioclase laths and they ended up being flow-banded near the edges, but not in the middle. This could use a diagram or two…

I like it — that was my gut reaction to this sight, but I’m pleased to hear you say it!

I agree with the two previous commenters: a dike intrusion is a process over time, not an instantaneous event. The initial pulse would have quenched immediately- I can’t tell from the photo, but I’d bet a thin section across the margin would show a much finer grain size to the outer side. Later intrusion carried phenocrysts, which would be aligned by shear. Still later, lower flow rate, less shear, less alignment. As I remember, plag tends to be somewhat buoyant in basaltic melts, so deeper (later) magma injection could be anticipated to have lower % phenocrysts; possibly more olivine + pyroxene.

Cool photos! I may have an opportunity to grab you a basalt pillow this coming week.

Awesome – thanks, Lockwood!

I agree with the two previous commenters: a dike intrusion is a process over time, not an instantaneous event. The initial pulse would have quenched immediately- I can’t tell from the photo, but I’d bet a thin section across the margin would show a much finer grain size to the outer side. Later intrusion carried phenocrysts, which would be aligned by shear. Still later, lower flow rate, less shear, less alignment. As I remember, plag tends to be somewhat buoyant in basaltic melts, so deeper (later) magma injection could be anticipated to have lower % phenocrysts; possibly more olivine + pyroxene.

Cool photos! I may have an opportunity to grab you a basalt pillow this coming week.

Awesome – thanks, Lockwood!

I agree with the two previous commenters: a dike intrusion is a process over time, not an instantaneous event. The initial pulse would have quenched immediately- I can’t tell from the photo, but I’d bet a thin section across the margin would show a much finer grain size to the outer side. Later intrusion carried phenocrysts, which would be aligned by shear. Still later, lower flow rate, less shear, less alignment. As I remember, plag tends to be somewhat buoyant in basaltic melts, so deeper (later) magma injection could be anticipated to have lower % phenocrysts; possibly more olivine + pyroxene.

Cool photos! I may have an opportunity to grab you a basalt pillow this coming week.

Awesome – thanks, Lockwood!

I agree with the two previous commenters: a dike intrusion is a process over time, not an instantaneous event. The initial pulse would have quenched immediately- I can’t tell from the photo, but I’d bet a thin section across the margin would show a much finer grain size to the outer side. Later intrusion carried phenocrysts, which would be aligned by shear. Still later, lower flow rate, less shear, less alignment. As I remember, plag tends to be somewhat buoyant in basaltic melts, so deeper (later) magma injection could be anticipated to have lower % phenocrysts; possibly more olivine + pyroxene.

Cool photos! I may have an opportunity to grab you a basalt pillow this coming week.

Awesome – thanks, Lockwood!

I agree with the two previous commenters: a dike intrusion is a process over time, not an instantaneous event. The initial pulse would have quenched immediately- I can’t tell from the photo, but I’d bet a thin section across the margin would show a much finer grain size to the outer side. Later intrusion carried phenocrysts, which would be aligned by shear. Still later, lower flow rate, less shear, less alignment. As I remember, plag tends to be somewhat buoyant in basaltic melts, so deeper (later) magma injection could be anticipated to have lower % phenocrysts; possibly more olivine + pyroxene.

Cool photos! I may have an opportunity to grab you a basalt pillow this coming week.

Awesome – thanks, Lockwood!

This a great post–very informative,clear progression of ideas and illustrations, with comments enhancing and amplifying the discussion. Excellent example of digital pedagogy. Folllowing this line of thinking, it would be great if theses and dissertations could go digital. A whole web site could be made from one’s research, with different pages for abstract, background, localities, methodology, conclusions and references. Besides the obvious use of videos, animations, geotagged photos, etc., references could be formatted to link to the original reference (if available on the web), Google Maps could be used to create maps that viewers could download, and Google Earth could be used to unite overlays with Google Map-generated placemarks. And thanks to Google, flickr, free website generators like Weebly, etc., all this capability is free!

This a great post–very informative,clear progression of ideas and illustrations, with comments enhancing and amplifying the discussion. Excellent example of digital pedagogy. Folllowing this line of thinking, it would be great if theses and dissertations could go digital. A whole web site could be made from one’s research, with different pages for abstract, background, localities, methodology, conclusions and references. Besides the obvious use of videos, animations, geotagged photos, etc., references could be formatted to link to the original reference (if available on the web), Google Maps could be used to create maps that viewers could download, and Google Earth could be used to unite overlays with Google Map-generated placemarks. And thanks to Google, flickr, free website generators like Weebly, etc., all this capability is free!

This a great post–very informative,clear progression of ideas and illustrations, with comments enhancing and amplifying the discussion. Excellent example of digital pedagogy. Folllowing this line of thinking, it would be great if theses and dissertations could go digital. A whole web site could be made from one’s research, with different pages for abstract, background, localities, methodology, conclusions and references. Besides the obvious use of videos, animations, geotagged photos, etc., references could be formatted to link to the original reference (if available on the web), Google Maps could be used to create maps that viewers could download, and Google Earth could be used to unite overlays with Google Map-generated placemarks. And thanks to Google, flickr, free website generators like Weebly, etc., all this capability is free!

This a great post–very informative,clear progression of ideas and illustrations, with comments enhancing and amplifying the discussion. Excellent example of digital pedagogy. Folllowing this line of thinking, it would be great if theses and dissertations could go digital. A whole web site could be made from one’s research, with different pages for abstract, background, localities, methodology, conclusions and references. Besides the obvious use of videos, animations, geotagged photos, etc., references could be formatted to link to the original reference (if available on the web), Google Maps could be used to create maps that viewers could download, and Google Earth could be used to unite overlays with Google Map-generated placemarks. And thanks to Google, flickr, free website generators like Weebly, etc., all this capability is free!

This a great post–very informative,clear progression of ideas and illustrations, with comments enhancing and amplifying the discussion. Excellent example of digital pedagogy. Folllowing this line of thinking, it would be great if theses and dissertations could go digital. A whole web site could be made from one’s research, with different pages for abstract, background, localities, methodology, conclusions and references. Besides the obvious use of videos, animations, geotagged photos, etc., references could be formatted to link to the original reference (if available on the web), Google Maps could be used to create maps that viewers could download, and Google Earth could be used to unite overlays with Google Map-generated placemarks. And thanks to Google, flickr, free website generators like Weebly, etc., all this capability is free!

Let me know what they find out. I was going to take a student up there this spring to do exactly the same work! Anyway, it would be nice if their work helps clear up the mess that is the Ediacaran apparent polar wander path!

Joe,

Will do!

CB