17 August 2022

Book report

Beneath the Rising, by Premee Mohamed

A novel of adventure, science fiction, and magic. Two teens from Canada embark on a mission to save the world. Though “mismatched” in terms of their demographics and wealth, they are united by the fact that they met as children when one terrorist’s bullet pierced them both. The story is told from the perspective of the boy, Nick, but what’s immediately crazy about the situation is his friend Joanna (nicknamed Johnny) is the smartest person in the world, having invented dozens of inventions that have reached every corner of the world and improved humanity’s lot. In the beginning of the story, she “does it again,” with a small, simple reactor that generates unlimited clean energy. But the new machine comes with a fearsome cost, bringing evil creatures into our world. Johnny knows how to stop it, but can she complete her globetrotting quest without Nick, despite his quotidian abilities? There pop-culture-infused banter is entertaining, but is there more to their relationship than meets the eye?

A novel of adventure, science fiction, and magic. Two teens from Canada embark on a mission to save the world. Though “mismatched” in terms of their demographics and wealth, they are united by the fact that they met as children when one terrorist’s bullet pierced them both. The story is told from the perspective of the boy, Nick, but what’s immediately crazy about the situation is his friend Joanna (nicknamed Johnny) is the smartest person in the world, having invented dozens of inventions that have reached every corner of the world and improved humanity’s lot. In the beginning of the story, she “does it again,” with a small, simple reactor that generates unlimited clean energy. But the new machine comes with a fearsome cost, bringing evil creatures into our world. Johnny knows how to stop it, but can she complete her globetrotting quest without Nick, despite his quotidian abilities? There pop-culture-infused banter is entertaining, but is there more to their relationship than meets the eye?

Mythos, by Stephen Fry

A free audiobook in Audible, at least through the end of this month. It’s all of Greek mythology, retold in the inimitable style of comedian Stephen Fry. It’s really, really good. Perfect bite-sized chapters, organized chronologically, and connecting the stories from antiquity with modern words and phrases. It is flooring to realize how much we are constantly surrounded by hand-me-downs from Greek mythology in modern American life, even if we are utterly aware of it. The antecedents in this collection persist in thousands of threads that bind together modern society. And it’s so well told! I found it absolutely charming to listen to; Fry’s language, voice, and choice of connections to elucidate make the listen a totally engaging experience. It’s scholarly, in a way – Fry backs out of the story to note areas of uncertainty when appropriate, about who begat who, or subtleties of translation, or where scholars don’t agree, but for the most part it’s a rollicking tale of good, evil, pride, greed, guile, innocence, and every other aspect of the human experience. Highly recommended.

A free audiobook in Audible, at least through the end of this month. It’s all of Greek mythology, retold in the inimitable style of comedian Stephen Fry. It’s really, really good. Perfect bite-sized chapters, organized chronologically, and connecting the stories from antiquity with modern words and phrases. It is flooring to realize how much we are constantly surrounded by hand-me-downs from Greek mythology in modern American life, even if we are utterly aware of it. The antecedents in this collection persist in thousands of threads that bind together modern society. And it’s so well told! I found it absolutely charming to listen to; Fry’s language, voice, and choice of connections to elucidate make the listen a totally engaging experience. It’s scholarly, in a way – Fry backs out of the story to note areas of uncertainty when appropriate, about who begat who, or subtleties of translation, or where scholars don’t agree, but for the most part it’s a rollicking tale of good, evil, pride, greed, guile, innocence, and every other aspect of the human experience. Highly recommended.

How College Works, by Daniel F. Chambliss and Christopher G. Takacs

An interesting and readable report on a multi-year qualitative study of factors that manifest in a successful college experience. The study was conducted at Hamilton College in New York, which is selective, private, small, and well-funded. I found much of the study to be insightful and meaningful, for instance that the most powerful part of the college experience is connecting with other people – friends, effective professors, and mentors. Other parts, like the powerful sense of identity that comes from exclusivity, seemed to me to be antithetical to the realm of higher education in which I teach: the community college. Where I work, it’s all about open access: anyone and everyone in our community is welcome to attend. A comparison may be valid here. Elsewhere, the authors note the the “small class size” metric by which colleges are judged (by the U.S. News & World Report rankings, for instance) is a flawed measure: for every student in a sought-after small class, there are some number of students who couldn’t get into it, and are in some other class instead – a larger one, perhaps, or perhaps a small class they hate (a required freshman seminar can be more nuisance than nirvana if you can’t get into your top few choices). I see the psychological benefits of exclusivity similarly: those on the inside may well bond and meld due to the institution’s (or fraternity’s, or band’s) strict requirements to enter (including financial), but that means you don’t get to hear the perspectives of those who are shut out of the group. Community colleges don’t have that issue. But I digress: Overall, I found How College Works to be an inspiring read. Connecting with students to support their success is my primary goal, and the primary unit by which colleges should be evaluated should be students, not courses, departments, or other institutional metrics. It’s about the students. We do well to ask them what they think.

An interesting and readable report on a multi-year qualitative study of factors that manifest in a successful college experience. The study was conducted at Hamilton College in New York, which is selective, private, small, and well-funded. I found much of the study to be insightful and meaningful, for instance that the most powerful part of the college experience is connecting with other people – friends, effective professors, and mentors. Other parts, like the powerful sense of identity that comes from exclusivity, seemed to me to be antithetical to the realm of higher education in which I teach: the community college. Where I work, it’s all about open access: anyone and everyone in our community is welcome to attend. A comparison may be valid here. Elsewhere, the authors note the the “small class size” metric by which colleges are judged (by the U.S. News & World Report rankings, for instance) is a flawed measure: for every student in a sought-after small class, there are some number of students who couldn’t get into it, and are in some other class instead – a larger one, perhaps, or perhaps a small class they hate (a required freshman seminar can be more nuisance than nirvana if you can’t get into your top few choices). I see the psychological benefits of exclusivity similarly: those on the inside may well bond and meld due to the institution’s (or fraternity’s, or band’s) strict requirements to enter (including financial), but that means you don’t get to hear the perspectives of those who are shut out of the group. Community colleges don’t have that issue. But I digress: Overall, I found How College Works to be an inspiring read. Connecting with students to support their success is my primary goal, and the primary unit by which colleges should be evaluated should be students, not courses, departments, or other institutional metrics. It’s about the students. We do well to ask them what they think.

What If?: Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions, by Randall Munroe

Such a fun book: I can’t believe it’s taken me this long to read it! (It was released in 2014; I listened to the Wil Wheaton narration.) The premise is that readers of XKCD send in questions – ridiculous questions – and then author Munroe does his best to answer them, with math, research, and humor. The result is very entertaining, and occasionally insightful. I had such fun reading it (listening to it). For what it’s worth, Wil Wheaton does an amazing job inflecting the nerdy umbrage of the text. Also worth noting is that the sequel, What if? 2, is about to be published, and based on a preview in this month’s WIRED magazine, looks to be just as delightful!

Such a fun book: I can’t believe it’s taken me this long to read it! (It was released in 2014; I listened to the Wil Wheaton narration.) The premise is that readers of XKCD send in questions – ridiculous questions – and then author Munroe does his best to answer them, with math, research, and humor. The result is very entertaining, and occasionally insightful. I had such fun reading it (listening to it). For what it’s worth, Wil Wheaton does an amazing job inflecting the nerdy umbrage of the text. Also worth noting is that the sequel, What if? 2, is about to be published, and based on a preview in this month’s WIRED magazine, looks to be just as delightful!

16 August 2022

Kinked metavolcanics of the Castine Formation, eastern Maine

Last week, I was in central-eastern coastal Maine, for a wedding, but I also made time for some geologizing. We stayed near Holbrook Island Sanctuary State Park, and spent several nice days there hiking and kayaking and exploring. The main rock unit I encountered is the Castine Formation, a Paleozoic-aged metavolcanic complex. The exact age appears uncertain: one source told me “Cambrian,” but elsewhere I see it listed as “Silurian-Devonian.” I used the fabulous app called Rock’d in the field as a guide for exploring.

I saw two principal varieties of rock: a coarse-grained lithology and a fine-grained one. Here’s a few views of the coarse stuff:

The coarse-grain size implies a certain violence to the deposition, and the grain shapes suggest proximity to the source. Note too the “matrix-supported” nature of the deposit: the largest clasts “float” in a finer-grained matrix, and don’t touch each other. This suggests very minimal winnowing of the fine material by consistent currents of water. Compositionally, these clasts are dominantly felsic, and were subjected to relatively low-grade metamorphism after they formed.

Here’s one outcrop I saw adjacent to Goose Pond, from a kayak:

(field of view about 10 m)

The cleanest part is under the overhanging tree branches in the upper left. Let’s zoom in:

(field of view about 3 m)

Those are some of the larger clasts I saw, with the biggest 0.3-0.4 m across.

So, in terms of interpretation: lahar deposits, or powerful pyroclastic flows?

This is part of Avalonia (or Avalon), a composite “microcontinental” terrane the originated adjacent to Gondwana, and accreted to ancestral North America during the Acadian Orogeny.

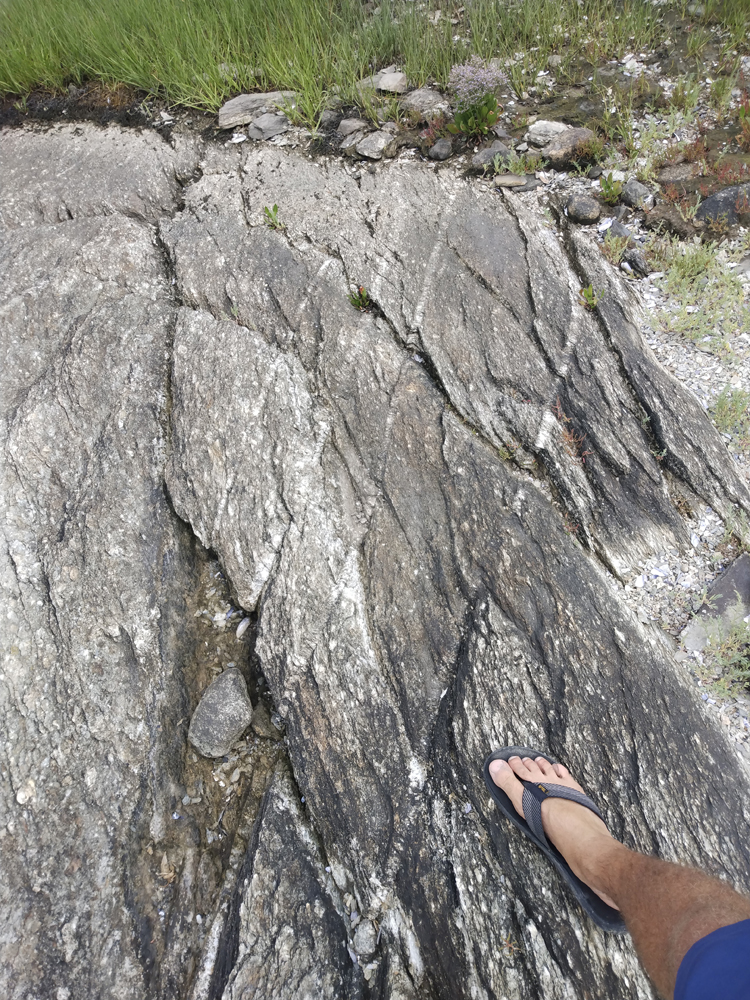

This one shows some well-developed foliation (running from lower left to upper right), induced by one or another episode of Appalachian mountain-building, I guess probably the Acadian:

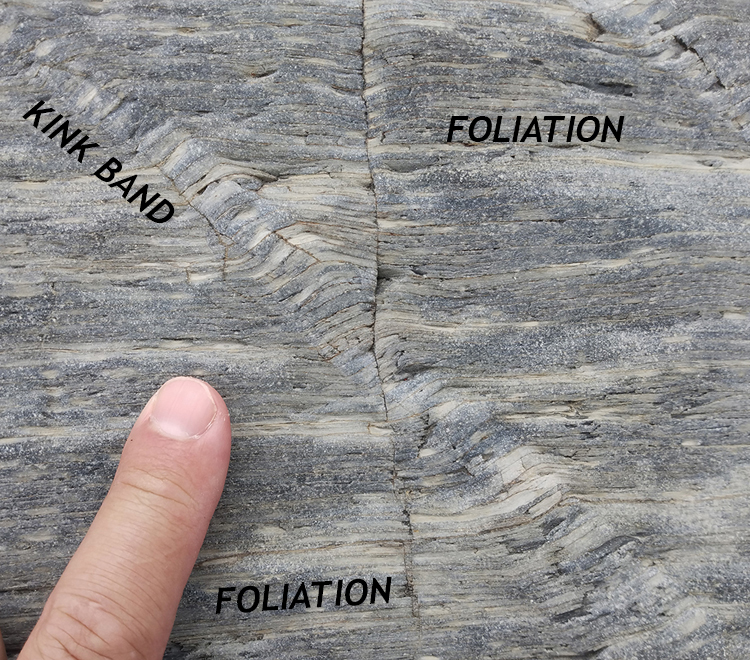

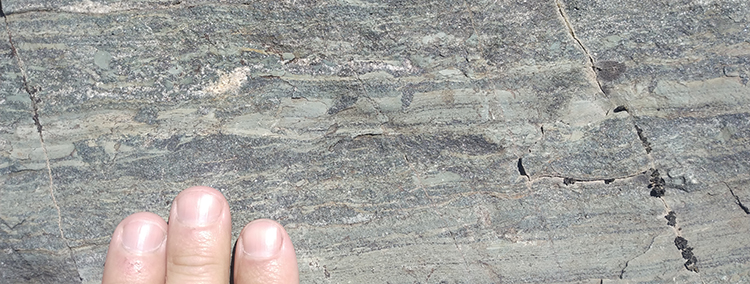

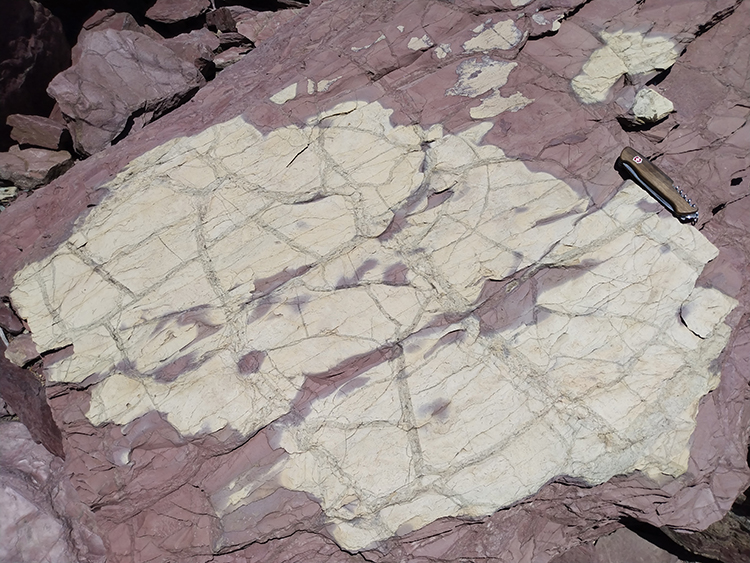

The other major lithology, the finer-grained metavolcanics, appeared to be more susceptible to deformation. Here’s an example showing a large kink fold disrupting foliation:

(Apologies for using my bare feet for scale!)

Well-developed kink bands in tight proximity, folding foliation:

More distributed kink bands:

A conjugate pair of kink bands, one of only two such intersections I observed:

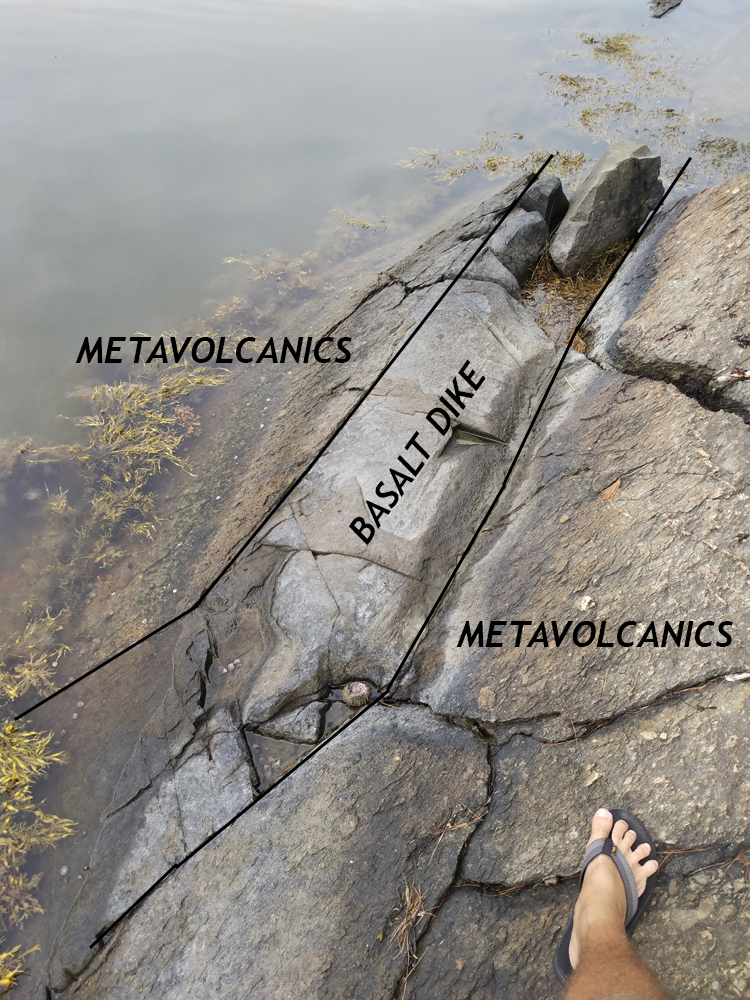

In two places, I saw basalt dikes cutting across the metavolcanic rocks:

These are probably Triassic in age, related to the opening of the Atlantic and the nearby Fundy rift basin. Note that they are neither discernibly metamorphosed, nor deformed.

In my experience, few things are as satisfying as exploring new and interesting outcrops, on foot and by kayak. For this, coastal Maine was a real treat: plenty of interesting texture and structure, exposed in a complicated 3D swath between the forest and the sea.

15 August 2022

Book report

Solitary, by Albert Woodfox

A first-person account of spending 40+ years in solitary confinement. Woodfox recounts his youth in New Orleans poverty, turning to robbery, being arrested, and then sentenced to Angola, the notorious plantation-turned-prison in Louisiana. He escapes at one point to end up in New York, where he learns of the Black Panthers, and transforms from a shiftless ne’er-do-well to a politically active change agent. Eventually he gets returned to Angola. There is framed for the murder of a prison guard, and his sentence jumps from a few years to life behind bars. Because of his political inclinations, he is committed to solitary confinement, in a cell by himself for 23 hours of every day. He can speak to other prisoners in adjacent cells, but for the most part he is utterly isolated. Somehow he manages to not go insane, and begins reading and educating himself. Time passes, lawsuits come and go, in many cases against Woodfox due to malfeasance on the part of prison officials, and his misery is compounded. The degrading manner he is treated with would make anyone cringe with indignation. After his third decade, his case becomes known to advocates in the wider world, who see his solitary confinement as a stark case of cruel and unusual punishment, and they push to change the practice. Woodfox also gets a retrial, and after the majority of his life incarcerated, he is finally able to walk out of Angola. Woodfox passed away the week before last, a free man.

A first-person account of spending 40+ years in solitary confinement. Woodfox recounts his youth in New Orleans poverty, turning to robbery, being arrested, and then sentenced to Angola, the notorious plantation-turned-prison in Louisiana. He escapes at one point to end up in New York, where he learns of the Black Panthers, and transforms from a shiftless ne’er-do-well to a politically active change agent. Eventually he gets returned to Angola. There is framed for the murder of a prison guard, and his sentence jumps from a few years to life behind bars. Because of his political inclinations, he is committed to solitary confinement, in a cell by himself for 23 hours of every day. He can speak to other prisoners in adjacent cells, but for the most part he is utterly isolated. Somehow he manages to not go insane, and begins reading and educating himself. Time passes, lawsuits come and go, in many cases against Woodfox due to malfeasance on the part of prison officials, and his misery is compounded. The degrading manner he is treated with would make anyone cringe with indignation. After his third decade, his case becomes known to advocates in the wider world, who see his solitary confinement as a stark case of cruel and unusual punishment, and they push to change the practice. Woodfox also gets a retrial, and after the majority of his life incarcerated, he is finally able to walk out of Angola. Woodfox passed away the week before last, a free man.

Rules of Civility and The Lincoln Highway, both by Amor Towles

With these two novels, I’ve exhausted all the published novels by Towles, which is an absolute shame, because he’s such a good writer. Each of these books (with A Gentleman in Moscow being the third) is its own unique creation, a universe unto itself. The details really don’t matter too much to me, but the care in writing about them is astounding, and each has satisfying plot twists that were unforeseen (by me, anyhow) but help to create a neat narrative arc. Rules of Civility was such a great book in terms of the universality of its central theme, adorned with the most delicious details. Lincoln Highway wasn’t quite as strong of a story in terms of how much it spoke to me, but it did feature narration from the point of view of numerous disparate characters, some of them trustworthy, some of them simple, and some of them caught up in their own self-justified mischief. The facility with which Towles moves the story along, jumping between these multiple points of view, is impressive. All these novels are great, and such a wonderful joy to read. Top-notch recommendations to each!

With these two novels, I’ve exhausted all the published novels by Towles, which is an absolute shame, because he’s such a good writer. Each of these books (with A Gentleman in Moscow being the third) is its own unique creation, a universe unto itself. The details really don’t matter too much to me, but the care in writing about them is astounding, and each has satisfying plot twists that were unforeseen (by me, anyhow) but help to create a neat narrative arc. Rules of Civility was such a great book in terms of the universality of its central theme, adorned with the most delicious details. Lincoln Highway wasn’t quite as strong of a story in terms of how much it spoke to me, but it did feature narration from the point of view of numerous disparate characters, some of them trustworthy, some of them simple, and some of them caught up in their own self-justified mischief. The facility with which Towles moves the story along, jumping between these multiple points of view, is impressive. All these novels are great, and such a wonderful joy to read. Top-notch recommendations to each!

The Internal Enemy, by Alan Taylor

A history of Virginia (and Maryland) during war with the British, particularly the War of 1812, its antecedents and aftermath. The specific focus here is how the slavery-based society of the pre-Civil-War United States left the slaveholding whites in constant fear of a violent uprising from those they enslaved. The title of this masterful history comes from the fact that they were battling on two fronts: the “external enemy” of the British navy, but also the “internal enemy” of their slaves. The author, Alan Taylor, is a UVA professor, and he weaves a well-paced exploration of how the British cannily exploited the fears slaveholders adjacent to the Chesapeake Bay while undercutting their economic success simply by accepting runaway slaves. Those who successfully escaped were given asylum aboard the British vessels. Most were eventually resettled in Bermuda or Nova Scotia, but to the Tidewater and Piedmont Virginian plantation owners, their great fear was that their former slaves would come back and wreak vengeance upon them. Recurring are characters you’ve heard of (Thomas Jefferson, for instance, James Madison and James Monroe), but also a family of Virginia landowners and slave-holders who squabble internally about choices that pit the moral instinct of some against the fraught relationship with their creditors, and their fears of their violence coming due in reciprocity.

A history of Virginia (and Maryland) during war with the British, particularly the War of 1812, its antecedents and aftermath. The specific focus here is how the slavery-based society of the pre-Civil-War United States left the slaveholding whites in constant fear of a violent uprising from those they enslaved. The title of this masterful history comes from the fact that they were battling on two fronts: the “external enemy” of the British navy, but also the “internal enemy” of their slaves. The author, Alan Taylor, is a UVA professor, and he weaves a well-paced exploration of how the British cannily exploited the fears slaveholders adjacent to the Chesapeake Bay while undercutting their economic success simply by accepting runaway slaves. Those who successfully escaped were given asylum aboard the British vessels. Most were eventually resettled in Bermuda or Nova Scotia, but to the Tidewater and Piedmont Virginian plantation owners, their great fear was that their former slaves would come back and wreak vengeance upon them. Recurring are characters you’ve heard of (Thomas Jefferson, for instance, James Madison and James Monroe), but also a family of Virginia landowners and slave-holders who squabble internally about choices that pit the moral instinct of some against the fraught relationship with their creditors, and their fears of their violence coming due in reciprocity.

For Want of Wings, by Jill Hunting

This nonfiction book is essentially a family history that attempts to draw together two partially connected aspects of the author’s ancestors. First, there is a deep commitment to the abolition of slavery in association with the notorious abolitionist (or “domestic terrorist,” depending on whose perspective you take) John Brown. Second is an interest in paleontology, and discoveries made in the American West under the guidance on Othniel Charles Marsh of Yale. The expedition west is chronicled in as much detail as possible: the author’s great grandfather is a student of Marsh’s, and she explores his biography as well as what he and the rest of the group saw out in the wilds of Kansas with assiduous research and some imagination. The most significant find is Hesperornis, a toothed bird from the Cretaceous chalk, which becomes known and celebrated as a transitional fossil, validating the idea of organic evolution. That’s much of the book, but not all – What remains is the author’s account of visiting Kansas herself, and chatting with the people she meets about fossils, and sharing a bit of her own life story, and that of her daughter, one of the founders of 350.org. She attempts to draw these various strands together, heady with awareness of the contingencies that led to the present moment. There are a great many tangents in this book, which evoked for me the feeling I used to get (pre-e-mail) reading letters from friends. I think if I were the editor of such a book, I’d be tempted to trim those back a bit, but the effect of retaining them all is to create a sense of informal familiarity with the author.

This nonfiction book is essentially a family history that attempts to draw together two partially connected aspects of the author’s ancestors. First, there is a deep commitment to the abolition of slavery in association with the notorious abolitionist (or “domestic terrorist,” depending on whose perspective you take) John Brown. Second is an interest in paleontology, and discoveries made in the American West under the guidance on Othniel Charles Marsh of Yale. The expedition west is chronicled in as much detail as possible: the author’s great grandfather is a student of Marsh’s, and she explores his biography as well as what he and the rest of the group saw out in the wilds of Kansas with assiduous research and some imagination. The most significant find is Hesperornis, a toothed bird from the Cretaceous chalk, which becomes known and celebrated as a transitional fossil, validating the idea of organic evolution. That’s much of the book, but not all – What remains is the author’s account of visiting Kansas herself, and chatting with the people she meets about fossils, and sharing a bit of her own life story, and that of her daughter, one of the founders of 350.org. She attempts to draw these various strands together, heady with awareness of the contingencies that led to the present moment. There are a great many tangents in this book, which evoked for me the feeling I used to get (pre-e-mail) reading letters from friends. I think if I were the editor of such a book, I’d be tempted to trim those back a bit, but the effect of retaining them all is to create a sense of informal familiarity with the author.

30 July 2022

Well-preserved mudcracks in Belt argillite, Glacier National Park, Montana

I spent last week in western Montana, teaching my annual “Geology of Glacier National Park” for Montana State University’s Master’s of Science in Science Education program. As usual, it was a fulfilling and enriching experience.

There are many great things about Glacier’s geology, but a perennial favorite for me is the abundance of truly ancient primary sedimentary structures, like these mud cracks:

Originally formed during the Mesoproterozoic, these delicate patterns speak of a very shallow Belt Sea, where mud deposited at high tide or in the wet season was then exposed to the air during low tide, or the dry season, inducing desiccation and contraction. The example above shows the resulting mud cracks filled with more mud, but they can be filled with sand, too, as this inverted block shows:

In cross-section, the mud cracks make V-like shapes where younger layers “bite” down into their predecessors. Here’s an example in green (chlorite-rich argillite of the Appekunny Formation) and another in red (hematite-rich argillite of the Grinnell Formation):

My favorite new example of this phenomenon is one I’ve walked by a dozen times before without noticing. It’s on the trail up to Grinnell Glacier, at the spot just before the waterfall-on-the-trail, where the route was closed this year due to a hazardous snowfield crossing. Forced to have my lunch there instead of atop the stromatolites up top, I was forced to examine my new surroundings. I appreciated this one especially:

Here, though the mud was deposited under oxidizing conditions (=red), later reducing fluids moved through the sediment (or sedimentary rock), altering blotchy portions of it (=pale green). I love the “palimpsest” overlap between the oxidation/reduction contrast and the pattern of mud cracks. Whether you’re a geochemist or sedimentologist, there’s a lot to love in this slab!

1 July 2022

Friday fold: lithified python

A quick Friday fold that I observed last month in a boulder of riprap at Chippokes State Park in Surry, Virginia. I have absolutely no idea where this rock was quarried; but it doesn’t look like anything I’m familiar with in Virginia, so maybe the Baltimore Mafic Complex???

Anyhow, it’s not native to the Coastal Plain, but it shows a pleasing fold train of green and gray amid the black of the surrounding rock. I’m reminded of a python’s muscly meanders.

Field of view is about 1 meter. Sorry to have neglected a sense of scale; mea culpa.

Happy Friday!

24 June 2022

Friday fold: Kinked Lynchburg metasediments near a soapstone body

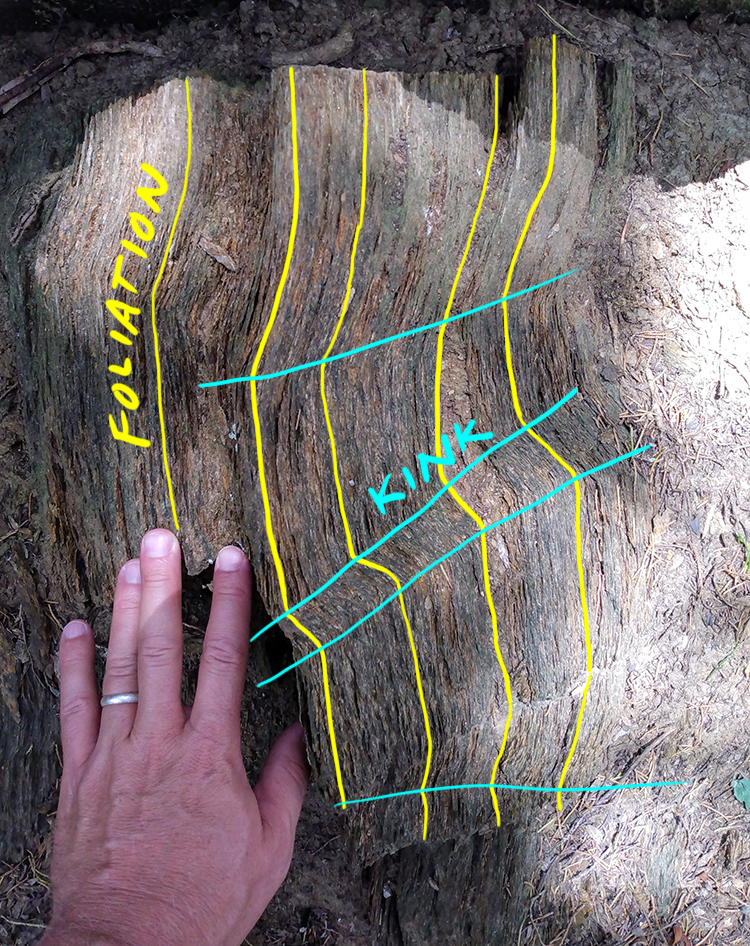

Earlier this week I showed an outcrop of overturned finely-bedded Lynchburg Group meta-sediments (Neoproterozoic in depositional age). Today, we revisit that same site, but this outcrop is 30 m away, and directly adjacent to a major soapstone body:

You can see the foliation is much more extreme here, with bedding obliterated, and that foliation has been kink-folded. Annotations:

These are probably Alleghanian-aged structures (both the foliation and the kinks that deform the foliation).

Here is a second example, located about 1 m away from the one I just showed:

Folds have been few and far between for me lately; so this was a nice treat. Happy Friday!

21 June 2022

Another example of overturned bedding

One of my favorite tricks is using bedding / cleavage intersections to identify tectonically inverted strata.

On a field trip yesterday to check out soapstone quarries in the Albemarle/Nelson border region, I got to see this lovely example of Lynchburg Group metasediments that showcased a textbook example of the phenomenon:

Bedding was initially horizontal, or close to it, and cleavage (formed under tectonic compression) initially vertical. Subsequent deformation rotated the beds here, first dipping shallowly to the left, then steeply to the left, then vertical, and now steeply to the right. Meanwhile, the cleavage tipped over to the left, and the angle between cleavage went from a right angle to increasingly acute. Now, both bedding and cleavage dip to the right, but bedding is steeper, and cleavage is more shallow. That relationship is a handy shortcut for spotting overturned beds.

I’m grateful to Chuck Bailey from William & Mary for bringing me along on this trip.

29 May 2022

Accretionary wedge turbidites from the Lost Coast

My wife just got back from a backpacking trip along the Lost Coast of California, from Mattole to Shelter Cove.

This is along the northern stretch of the San Andreas Fault, just south of the tectonic triple junction at Cape Mendocino.

My wife was kind enough to document some of the geology along the coast there, and to allow me to share the images here…

The local rocks are siliciclastic turbidites, shales and graywackes mainly – with a bit of conglomerate thrown in. These were deposited in deep water due to density currents (underwater avalanches called turbidity currents), which drop their load of grains in order of the particles’ weight, as this boulder of stacked graded beds shows:

A couple of close-ups of laminations and cross-bedding within the sandier turbidites, again showing a fining-upward pattern:

Here’s a muddier package, interspersed with sandy layers:

These deep sea sediments were scraped off the subducted Farallon Plate during the Mesozoic, and were crumpled and deformed as they joined the accretionary wedge. The contrast of the light sands and dark muds shows off the resulting deformation well:

Is it a fold or a fault?

…Yes!

This is my favorite of the photos my wife brought back: Our friend Kristie stands in front of a shale-dominated outcrop, but the handful of graywacke layers show a neat pop-up feature (to her left):

Let’s zoom in:

Annotated, with faults in yellow and kinematic indicator arrows in red:

This outcrop shows a scaly pattern, with a vertical foliation, suggesting it was a more dispersed zone of deformation, a shear zone within the subducted sediments.

Like much of coastal northern California, the Lost Coast has experienced uplift. Once the downward drag of subduction was relaxed, it allowed the flexible edge of California to bob upward. As evidence of that, consider this angular unconformity:

The lower half of that outcrop is tilted, folded, and faulted turbidites like those we have been looking at, but then there is a prominent line of light-colored boulders marking an ancient erosional surface, probably a wave-cut platform. Above that, plenty of beach gravels to a thickness of many meters, much like the modern beach in the foreground. All that was at or below sea level, and now has been lofted well above the reach of the waves.

This recent uplift is preserved in the shape of the land, too, like the two prominent marine terraces seen in this oblique shot along the coast:

Inspiring geology can be found along the Lost Coast.

16 May 2022

Qwitter

On April 25th, it was announced that Elon Musk had arranged to buy the social media company Twitter. He had just attained majority shareholder status a few weeks earlier. I’ve been an avid Twitter user for twelve years, accruing 11.5K followers over that interval, and very much enjoying the conversation — but I decided to leave the service when the sale was announced. Musk has articulated both an interest in less moderation on the forum, and a few days later shared a cartoon of what is presumably his political perspective, which is that the right is unchanging, but the left is more extreme. These harbingers potentially clear the way for rightwing extremists to repopulate Twitter. Chief among them may be the former president and coup cheerleader, and Musk has more recently stated that he would reverse TFG’s permanent ban on Twitter. I want no part of a space that lets hatred flow, poisoning the public discourse. So I decided to leave.

But it’s more than that: The increased time I’ve spent on Twitter over the past several years has led to some negative consequences. For one, it’s meant more of my geocreative energy has been expended in that space, with a consequent neglect forming here on my blog. I’m not sure about the role of blogs in the modern Internet landscape, but long form is probably a medium better suited to my talents. Second, there’s the issue of how Twitter impacted me emotionally: I feel like the constant stream of horrible news – about TFG, about COVID, shootings and racial injustice, the continuing lack of progress combating climate change, about the Supreme Court, about half of my fellow Americans — it’s all such a bummer. Stress and depression result. My wife first identified this trend: the more time I spent on Twitter, the grouchier I became. Finally, it’s just about time and attention. I had fallen into the habit of constantly checking Twitter – on my laptop, on my phone – a sort of addiction to the site. It didn’t feel healthy, and it distracted me from focusing on other matters, on whatever I was doing in that moment.

So I left; I deleted the app from my phone; I deleted the Twitter widget from this blog.

The past couple of days have brought another development, with Musk proclaiming the acquisition deal was on hold, which raises the possibility that I could ethically see my way to returning, but the issues outlined in paragraph 2 would still persist, so if that came to pass, It would be most healthy if I were to change things up a bit.

We’ll see. For the time being, my plans are to put my geocreative energy into a new video series (I’ll post about it here once it’s up and running) and into finishing a few case studies for my online Historical Geology text”book.”

13 May 2022

Super Volcanoes, by Robin George Andrews

A terrific debut book by Robin George Andrews, who trained as a volcanologist but diverted from primary research into popular science writing. (He has also done a bunch of freelancing for National Geographic, Scientific American, and the like.) The book profiles Kilauea, Yellowstone, Ol Doinyo Lengai, the oceanic ridge system (including Iceland), the Moon, Mars, Venus, and the cryovolcanoes of the outer solar system, plus bookending diversions into Vesuvius and Fuji. I was surprised at how much of the page count was devoted to extraterrestrial volcanism, but that decision certainly leaves plenty of Earthly volcanoes available to be profiled in Super Volcanoes II. The writing style is very excited and skews to the popular side of the jargon-fluff spectrum. The decision to de-emphasize jargon is laudable, but I found that the language can tend to be a bit flowery, especially in the first half of the book. For instance, he refers to the magma chamber below Yellowstone as a “dragon,” a “cupola,”, a “missile,” a “grenade,” and (you can hear the thesaurus pages flipping) a “wyvern.” It erupts “shattered fire.” These metaphors can be doubtless engaging with some audiences, but my taste is for a bit more direct language. It’s a fine line, and I’m not sure whether there’s a clear way to nail “just the right amount of technical detail,” but I think one technique (employed by Andrews) is to weave in brief interviews with working volcanologists, allowing them to use their own words to describe eruptive phenomena, which then gives Andrews the latitude to “translate.” He does a fine job with presenting these people as humans, and somehow makes the reader feel welcomed by the volcanological community. All told, I found Super Volcanoes an enjoyable read, and it will have a place of honor on my geological bookshelf.

A terrific debut book by Robin George Andrews, who trained as a volcanologist but diverted from primary research into popular science writing. (He has also done a bunch of freelancing for National Geographic, Scientific American, and the like.) The book profiles Kilauea, Yellowstone, Ol Doinyo Lengai, the oceanic ridge system (including Iceland), the Moon, Mars, Venus, and the cryovolcanoes of the outer solar system, plus bookending diversions into Vesuvius and Fuji. I was surprised at how much of the page count was devoted to extraterrestrial volcanism, but that decision certainly leaves plenty of Earthly volcanoes available to be profiled in Super Volcanoes II. The writing style is very excited and skews to the popular side of the jargon-fluff spectrum. The decision to de-emphasize jargon is laudable, but I found that the language can tend to be a bit flowery, especially in the first half of the book. For instance, he refers to the magma chamber below Yellowstone as a “dragon,” a “cupola,”, a “missile,” a “grenade,” and (you can hear the thesaurus pages flipping) a “wyvern.” It erupts “shattered fire.” These metaphors can be doubtless engaging with some audiences, but my taste is for a bit more direct language. It’s a fine line, and I’m not sure whether there’s a clear way to nail “just the right amount of technical detail,” but I think one technique (employed by Andrews) is to weave in brief interviews with working volcanologists, allowing them to use their own words to describe eruptive phenomena, which then gives Andrews the latitude to “translate.” He does a fine job with presenting these people as humans, and somehow makes the reader feel welcomed by the volcanological community. All told, I found Super Volcanoes an enjoyable read, and it will have a place of honor on my geological bookshelf.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.