13 September 2016

Sikuliaq week 1 recap: Through the ice

Posted by larryohanlon

This is the latest in a series of dispatches from scientists and education officers aboard the National Science Foundation’s R/V Sikuliaq. Read more posts here. Track the Sikuliaq’s progress here.

By Kim Kenny

Today marks one full week at sea. We’ve gone through the Bering Strait and Chukchi Sea into the Beaufort Sea, where we worked our way into the Beaufort Basin. Then we turned southwest and are now back in the northeastern part of the Chukchi Sea. We’ve recovered and replaced a mooring; steamed along the DBO 6 line, taking 18 CTD casts along the way; continued to collect surface underway measurements; prepped for the deployment of the super sucker sled, multi-corer, and glider (each very cool pieces of equipment that warrant future explanation); and most excitingly (at least for this unseasoned Arctic visitor who still gets giddy at the idea of being on a ship), we entered ice.

We first entered the ice on Monday, Sept 5 – when this footage way taken – on our way to DBO 6. We entered it again yesterday, Saturday, Sept 10 on our way back into the Chukchi Sea.

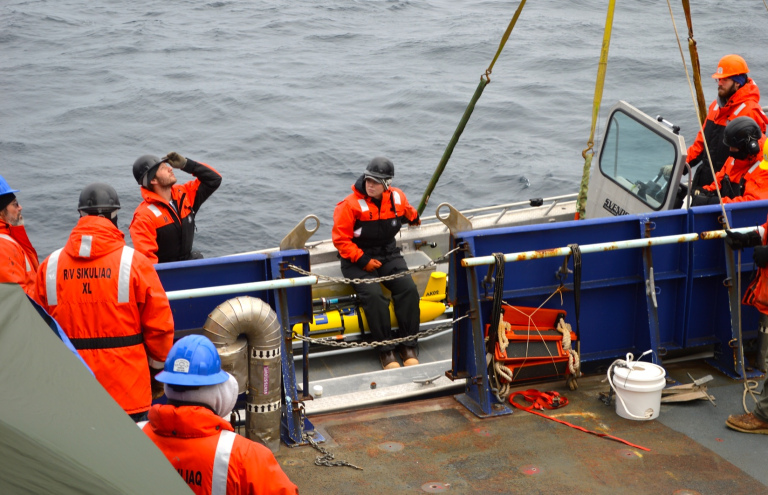

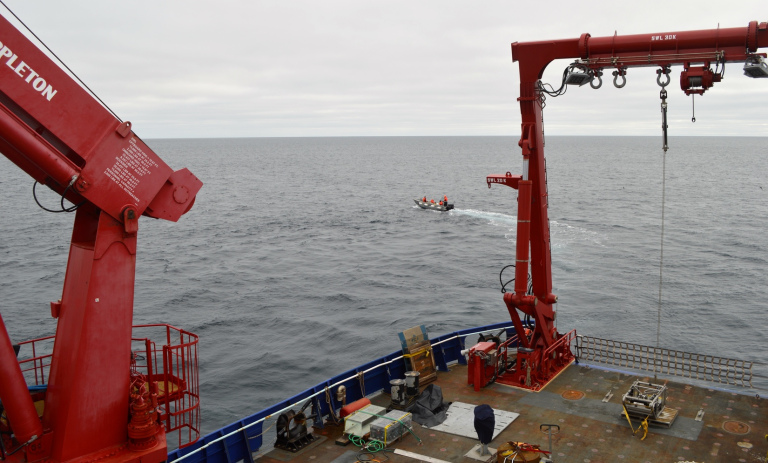

Today was a day of shifting plans and deployments. Burke’s team deployed the super sucker this morning, but discovered it wasn’t working properly, so they had to bring it back in for trouble-shooting. They found the problem – a short in their cable – and are working on the aft deck to fix it. They’ll need to be awake for the deployment and 24hrs of data collection, and have already been working long hours to prepare it, so they’ll probably take a break for sleep before the next attempt at deployment. If preparations for the multi-corer are finished soon, Miguel’s team may be able to take coring samples tonight. This afternoon, Brita Irving, a research scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, made an attempt at deploying the glider she’s been preparing. She and three crew members took the Sikuliaq’s skiff out about 50ft from the ship to send the glider on its way, but it’s instruments weren’t functioning properly. Apparently gliders are notoriously finicky. So Brita has it back on the ship and is working on making adjustments.

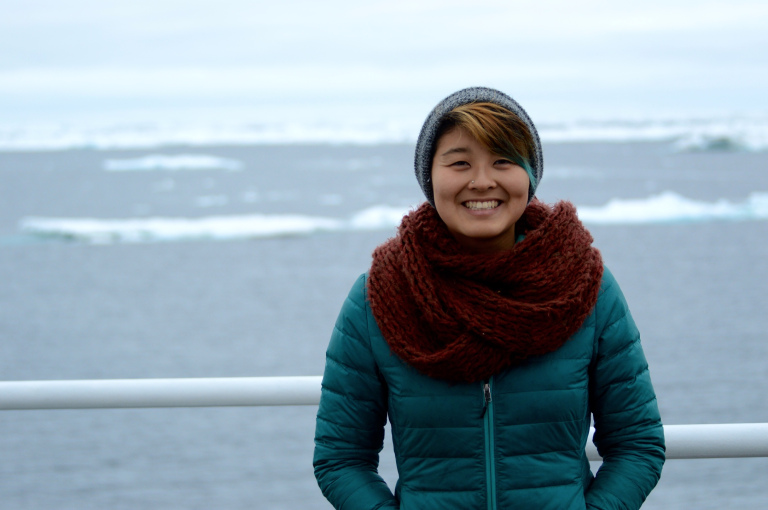

After a week at sea, the rhythm of Sikuliaq life is becoming more apparent. During the glider operation, and in all the operations I’ve seen so far, everyone involved manages to intersperse the serious passing of information with light-hearted banter. Today, Miguel messaged on g-chat with a man onshore about the music they were listening to while waiting for a satellite to connect with the glider (Chopin’s Waltz no. 7 in C-sharp minor; ACDC). Paul, Elliot, and Arty talked about what they’d do for vacation in Alaska; Laurie, Miguel, and Ethan about hunting and berry-picking while they waited to deploy. Little jokes and casual chatter are slipped in between serious talks, more so than in other work environments. The switch from work to play and back again can be fast. It’s easier to know people more quickly. There’s a fair amount of swearing. Coffee is highly valued. Attire is casual-practical all the time. Sometimes things seem to be happening all at once, and then not at all. It can be hurry-up-and-wait. Work might need to be done for 22hrs straight or we might have a full day of steaming with “nothing” to do. Time blurs here, not only because of the extended daylight hours of the Arctic. Sometimes a scientist’s shift will change from midnight-4am to 2pm-8pm to all day depending on what science there is to do. Crew members have more easily predictable shifts, though those can change too. Sundays are haircut days, courtesy of Paul (the bosun). There are a handful of crew members I have yet to meet because they work in the engine room during the wee hours of the morning. But by now I’ve seen the ship operating at every hour of the day, and the striking thing is the obvious fact that it never stops operating – the doors don’t open and close for business hours like in other workplaces. Someone is always working. Time of the day and days of the week don’t really matter anyway as long as the work gets done when it needs to be done.

Meals are an important reference point – breakfast 7:30-8:30, lunch 11:30-12:30, dinner 5-6. We are completely spoiled with the food – Mark, Kim, and Terence do an amazing job providing us with pad thai, lamb shank, stuffed tomatoes, daily salads. I easily eat better here than I do at home, which is not the norm for research cruises. There is an nonalcoholic “elixir” the galley sometimes offers, especially to people feeling sick. (Mary-Kate, who has been working in what is essentially a walk-in freezer, had a cough for a few days straight and so often partook.) It’s a mix of apple cider, vinegar, and mystery spices. Some of the crew can be seen in the galley taking shots of it at the start of the day. Alcohol is not allowed onboard, so a beer back in Nome will be much appreciated.

People tend to have their domains on the ship. The labs, galley, bridge, computer room, engineering deck, aft deck, lounge. Scientists sleep on the 01 deck (ship equivalent of first floor), crew on the 02 deck. Most rooms, doors, passageways, pipes and equipment are clearly labelled. Despite this, it can sometimes be surprisingly hard to find people. Turns out gossip still exists on a 260ft ship with 42 people onboard. All major planning decisions go through Laurie as the chief scientist, so she ends up needing to repeat herself to multiple people throughout the day. There’s a whiteboard in the galley where people can write public messages. The announcement of a Sharknado viewing was made here (Highly recommended. Sadly we don’t have Sharknado 2 onboard, but someone has Sharknado 3. Looking forward to more stock footage and Tara Reid). Also on this board is a list of suggested names for a new Sikuliaq support vessel. No Boaty McBoatFace, but suggestions include “Biscuits n Wavy,” “Angler Management,” and “Siku,” Inupiaq for “small ice.”

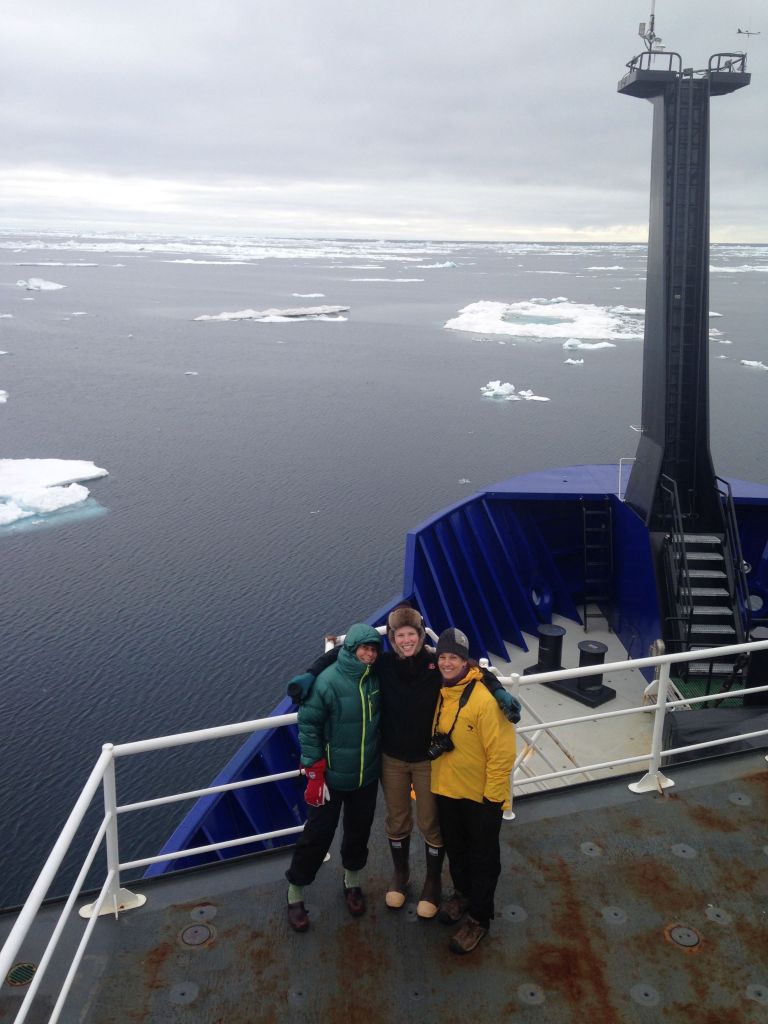

Sea ice

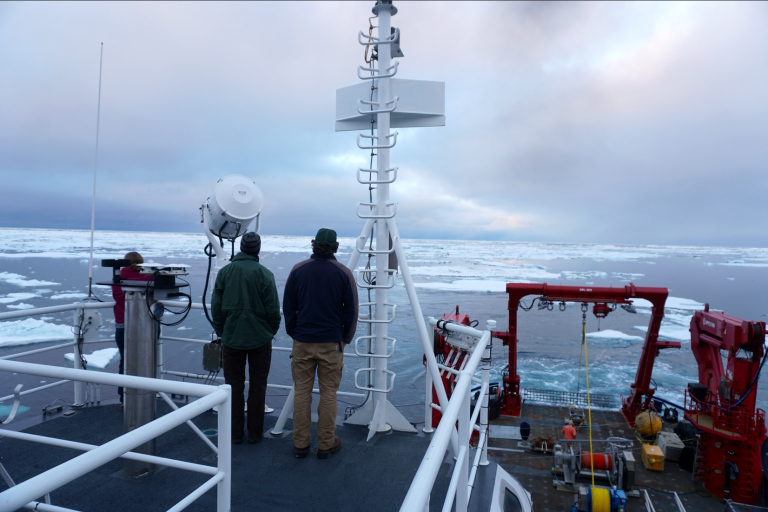

The first time we saw the ice, I thought mostly of the different shapes and colors it has, noticed the lighter blue pools contained in its crevices, the small fish that would appear after we broke a piece, how it stretched on to the horizon not in one big sheet but in fragmented sections. The salinity of the water around the ice is very high when it first forms, but after about a year the pools of water contained by the ice can be fresh enough to drink. There’s an entire binder full of ice types on the bridge. It’s helpful for the crewmen to know the different types so they can decide the best “leads” to travel through. Most of the time they try to avoid the ice altogether. That first day almost everyone got up on the bridge at some point to take a look. We huddled around windows with binoculars to see walruses and polar bears. I love the way a herd of walruses moves in the water – an undulating mass of brown blubber, like they’re tripping over themselves as they swim. (A group of walruses is called a “herd”. This was a point of contention among us until googling capability was restored. I still prefer “tuscan” or “walri,” but “herd” is technically correct.)

The second time we saw the ice, it was thicker and more widespread. This time my thoughts weren’t focused on its beauty, but its power. You can feel the rumbling shake of the ship as we ease into a particularly large piece of ice, hear the scrape of it along the hull, the cracking beneath our weight. I stood on deck when the ship was making its way through a denser section of ice, felt us halt as we entered a piece and thought – what if it just cracked the hull. Of course, we were fine, but I was struck by the real feeling of fear I had in that moment. Our 260ft ship seemed like a play toy in a big frozen tub. I try to imagine what it would be like to truly be in a dangerous situation completely surrounded by ice, or what it must’ve been like 100 years ago exploring this place in a wooden ship, without the comforting knowledge that the coast guard could come to the rescue. At 2am this morning we could still feel it scrape along the hull from our bunks, but by breakfast-time the porthole view returned to the normal expanse of blue-grey waves.

The ice delayed us and forced the scientists to adjust their plans because it covers some of the sites originally intended for data collection. As mentioned in the previous post, we’re on our way to DBO 4. The ice isn’t usually in this part of the Arctic during this time of year, so the chief scientist has had to shuffle between plans and juggle the timing of different deployments.

Such is science, and scientific cruises – the unexpected happens, you adjust, you find a way to make it work because you have to, you let go of the things you can’t control, you take what comes. We have about two more weeks at sea to get more data, and we’ll be making full use of the time.

— Kim Kenny is a freelance journalist who specializes in science writing and multimedia. This post was originally published on thedynamicarctic.wordpress.com

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.