21 July 2015

Study: Most rain comes from ice clouds

Posted by Nanci Bompey

By Johannes Mülmenstädt

A new study finds that over land outside the tropics, only 1 percent of rain events involve ice-free clouds.

Credit: Kevin Gordon/Wikimedia Commons

Benjamin Franklin was the first to surmise that, even on a hot summer’s day, the raindrops falling on our heads might begin life as ice particles at high altitudes. In the centuries since 1780 it became possible to probe the atmosphere directly by balloon and by aircraft, and remotely from the ground and from satellites. These observations confirmed Franklin’s suspicion. However, two questions remain: how large are the fractions of rain produced by liquid clouds and by ice clouds? And how variable are they over the globe and over time?

A new study accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, gives the answers. The new study confirms the prevalence of rain from ice clouds at mid-latitudes, and shows rain from ice clouds prevails to an astonishing extent, according to Johannes Mülmenstädt, a scientist at the Institute of Meteorology at Universität Leipzig in Germany and the study’s lead author.

Over land outside the tropics, only 1 percent of rain events involve ice-free clouds, according to the new study. Even in the tropics, where rain from liquid clouds is more common, there is a remarkable contrast between rain events over land and ocean, according to Mülmenstädt.

The study was made possible by three satellites, designed and launched by NASA and its partners in Europe and Japan, that fly in close formation and provide a picture of the Earth’s atmosphere far clearer than any of the constellation’s individual components. Over the course of five years, the satellites, named Aqua, Calipso, and CloudSat, have taken snapshots of more than 50 million raining clouds, which are made freely available to scientists worldwide. Among the instruments the satellites carry are a cloud radar that detects large raindrops and ice crystals; a powerful green laser beam and light detector sensitive to small liquid droplets and can distinguish between liquid and ice clouds; and a spectroradiometer that measures the reflection of sunlight from clouds and infers cloud properties like the total liquid and ice content and the size of cloud droplets or ice particles near the top of the cloud.

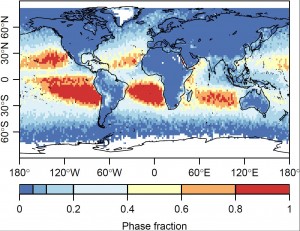

“Using the combined information from these satellites, we now know where on Earth rain falls from liquid clouds and where it falls from ice clouds, and the results are striking,” Mülmenstädt said.

The new findings may be a sign of human influence on the global water cycle, according to the study’s authors.

The global distribution of the fraction of rain from liquid-only clouds. A new study finds that rain from ice clouds prevails to an astonishing extent.

Credit: Johannes Mülmenstädt

Liquid clouds tend to produce drizzle, while ice clouds produce more intense rain. Tiny particles, or “aerosols”, that are suspended in the atmosphere may be able to influence clouds in their infancy and determine whether they grow into drizzling liquid clouds or intensely raining ice clouds. And these aerosols are more abundant over land, in part due to the combustion processes that power human activity, according to the study’s authors.

“There are many other differences between the marine and continental atmospheres, but one big one is aerosols. How much of a role they play—and whether the preindustrial atmosphere may indeed have seen more drizzle and less intense rainfall than the present day atmosphere—is the question we’ll be addressing next,” said Mülmenstädt. “The results of this study are consistent with an aerosol effect: clouds over land have a bigger droplet size gap to overcome before they can begin to drizzle than clouds over the ocean. But that by itself is not yet enough to prove an aerosol influence.”

The study’s results also provide an observational crosscheck that may be useful for fine-tuning atmospheric models for weather and climate prediction. The portrait that these models paint of rain is less accurate than their representation of other processes. Frequency and intensity of rain in the models are especially troublesome, Mülmenstädt said.

“Checking whether models produce virtually all their rain over land from ice clouds, as our observations say they should, may be a fruitful way to attack this problem,” he said.

In light of the importance of rain for aspects of life from agriculture to transportation disruptions to widespread flood damage, this is an area in urgent need of continued research, Mülmenstädt added.

— Guest blogger Johannes Mülmenstädt is a scientist at the Institute of Meteorology at Universität Leipzig and the study’s lead author. This post also appears as a press release on the university’s website.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.