8 September 2016

Into the Atlin wild

Posted by Nanci Bompey

By Rebecca Fowler

This is the second in a series of dispatches from Rebecca Fowler, a science writer documenting the work of scientists conducting fieldwork at the Atlin ophiolite in British Columbia. Read her other post here.

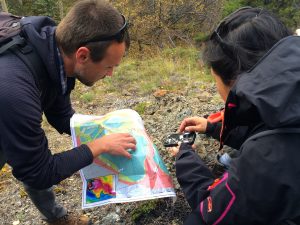

Andreas Beinlich and Masako Tominaga with the geological map our group is using to navigate the Atlin ophiolite.

If you are a field geologist—or thinking about becoming one—you’d better like hiking bushwhacking. And granola bars.

Where we are—Atlin, British Columbia—there are few trails and more than a few gaps in knowledge about the area’s geology. Our research team uses a geological map last updated in the early 2000s to navigate the terrain and find specific outcrops along the Atlin ophiolite where there are boundaries, or reaction fronts, places where the original rock was at some point altered by hot carbon dioxide-bearing fluids within the Earth’s crust.

Masako Tominaga and Andreas Beinlich, the leaders of this expedition, are searching for outcrops where, ideally, peridotite meets serpentinite, or where serpentinite meets listvenite. (Remember that during the alteration process, peridotite turns into serpentinite, or listvenite depending on the carbon dioxide concentration of the hot fluid that alters the rock.)

Use of this map often has us beating a path through brambles, scrambling up steep, rock-strewn hillsides, weaving among slender paper birch trees and tramping across pillowy moss. When we’re fortunate, these woodland rambles lead to an outcrop with a promising reaction front, and we stop so Masako and Andreas can collect samples and measurements. Like many explorers, our team names sites based on the characteristics of their location. We’ve chanced upon Serpentine Island, named for an isolated serpentine outcrop in the mist of listvenite, and trekked through The Litter Box, named for the astonishing amount of animal scat found on the premises.

In the instance that we find a site worth sampling, the four members of this research team, Masako and Andreas, plus Ian Power and Estefania (Fani) Ortiz, drop their backpacks and spring into action. Masako, Andreas and Ian poke around with their rock hammers, chipping away at the outcrop and discussing the best to collect samples. Once a sampling spot is selected, Masako and Fani mark a line across it with a measuring tape and Fani records the GPS coordinates of the beginning and end of the line. Next Masako walks the line, up and down, doing a geophysical survey with a portable high precision magnetometer in her backpack; the instrument senses the magnetic field of the rocks produced by the outcrop. Andreas selects rock samples along this same line, sometimes using his rock hammer to make them a reasonable size—if our bags are too heavy the kind people at Air Canada won’t put us on the flight back to Vancouver.

Ian follows behind Andreas, putting the rock samples in clear plastic bags and labeling each bag with the location and date. Meanwhile, Fani takes hundreds of photos of the outcrop from all sides. She’ll use these to create a three-dimensional topographic computer model of the site using a technique called photogrammetry.

When these tasks are done, Masako, Andreas and Ian consult the map and discuss which location and outcrop we should visit next. One discovery made on this trip is that the map, being made in pre-GPS times, isn’t always accurate. So we rely heavily on Ian, who has been to Atlin for fieldwork five times before. And this is OK because Ian knows the area fairly well and part of our reason for being here is to verify the outcrops noted on the map and update it when necessary.

We’re also in Atlin to collect rock samples and geophysical data, which will be used to determine which outcrops Masako and Andreas will sample in 2017. The 2016 data will also be used to better understand the carbonation process in the Atlin ophiolite—how peridotite becomes serpentinite, and how serpentinite later becomes listvenite. On a large scale, this knowledge could later be used to inform atmospheric carbon dioxide monitoring and mitigation efforts.

We have two full days left in the field to find outcrops, collect data, plan for next year’s expedition and see moose. If anyone knows where the moose of Atlin spend their time, you can reach us in Cabin 10, Atlin, British Columbia.

To see more photos from our expedition, check out the AGU’s Instagram account.

One of our hikes led us high on a hill overlooking Atlin Lake; Ian Power and Andreas are at the far right. We’re a little spoiled by the views.

— Rebecca Fowler is a science writer who divides her time between freelance projects and communications for Columbia University’s Center for Climate and Life.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

Granola bars?? I thought it was Quaker instant oatmeal, Cup o’Noodles and road kill. These kids today …

Looks like not exactly the worst place in the world for fieldwork, though …