12 September 2016

Walking the line: DBO 6

Posted by larryohanlon

This is the latest in a series of dispatches from scientists and education officers aboard the National Science Foundation’s R/V Sikuliaq. Read more posts here. Track the Sikuliaq’s progress here.

By Kim Kenny

CTDs for days

Eager scientists peak through the small circular window of the water-tight door between the wet lab and the Baltic room. When the all-clear is given and the door opened, they clamber en masse toward the CTD. Rachel delegates tasks with urgency – Debbie, Jenna, Mary-Kate, Katie, and Brianna go to their assigned stations. They squat next to nozzles and fill bottles with water. This water came from the cold, dark depths of the Beaufort Basin. It was collected in 10L Niskin bottles (no one could remember exactly who Niskin was. Onboard Wikipedia says Shale Niksin first came up with the idea in 1966) – essentially 4ft long tubes with caps at both ends. These are “fired” – or told to close to gather water – when an operator in the computer room of the ship clicks a button on a screen.

Rachel’s team needs to be quick. The water samples must be kept in conditions as close to what they were collected in as possible. More to the point, the microscopic organisms in the water must be kept in similar conditions; these organisms might not react the same way to tests if they’re not kept in an environment they’re used to. And that would decrease the accuracy of the team’s results. Kimberley and Miguel join the fray, but are slightly less hurried since they don’t need to store their samples with such speed. (They’re looking at particles in the water that won’t change much if the water warms slightly.) The eight people around the CTD occasionally joke around while jostling for position.

There are 24 Niskin bottles in a circle on the rosette of the cylindrical, large refrigerator-sized CTD. The apparatus is attached to a winch operated by a crew member in a closet-sized room on the 01 deck (ship equivalent of first floor) that overlooks the Baltic room. From the bridge, the crew member on watch can see the CTD enter and leave the water, and confirms with the winch operator whether the ship is in a good position for deployment. The Sikuliaq has special “dynamic positioning” that allows it to stay in one place without anchoring. The person on the bridge needs to make sure the ship doesn’t drift far enough to endanger the deployment. In the computer room, a wall of screens show changing graphs and tables that paint a picture of the water conditions – green for chlorophyl a, blue and pink and yellow for phycoerythrin, orange and purple for crude oil. Coordinated communication via radio from the bridge to the winch operator to the computer room and finally to the Baltic room where the CTD is pulled in is necessary to make this standard oceanographic operation go smoothly. The real heavy lifter is a machine down in the engine room – a winch that pulls up the electrical wires attached to the CTD. The whole process can take hours, depending on how deep the CTD is sent. This cast went down to almost 4,000 meters, the deepest of the cruise. The scientists have waited four hours for it to go down and come back up.

When enough bottles are filled, they’re loaded into a white and blue Rubbermaid tub. This is hauled back through the wet lab and down the hall to the analytical lab. From there the quick work of bagging and storing begins. The lab is kept dark, except for a single red light, to imitate darkness at depth. Someone usually has music playing; tonight it’s country. The bottles are put in mesh bags to further simulate darkness (different bags have different thicknesses to let in different amounts of light), and taken to incubation. They’re hauled out on the aft deck and put into two rectangular glass cases filled with water kept at the same temperature the samples were collected from. They’ll be left here for 24 hours to allow the microscopic newcomers to equilibrate before further testing.

This particular CTD cast is special because attached to it are three bags filled with decorated styrofoam cups. It’s a fun little gimmick to send styrofoam cups down with a CTD, where the oxygen gets squeezed out, and pull them back up again when they’ve shrunk to shot glass size. People drew polar bears, renditions of the Sikuliaq, names, messages, now memorialized as Arctic souvenirs.

(Coming soon: CTD video)

DBO 6

Much of the past four days have been spent doing CTDs. Not all the casts involve a frenzied collection of water; some are sent down to collect data and then come back up without fanfare. We’ve done 18 CTDs since getting through the Bering Strait and arriving at the start of the DBO 6 line. The DBO 6 line is a series of points stretching from the shallow part of the Beaufort Basin near the coast out to deeper water.

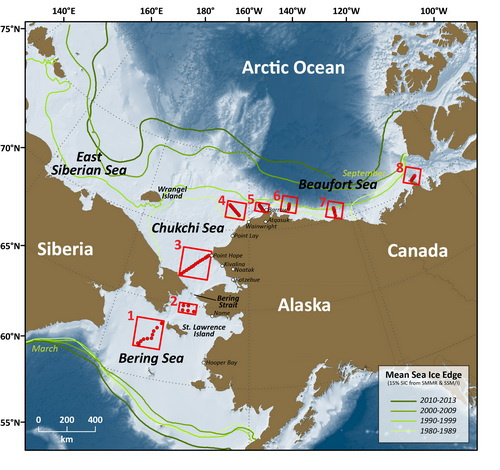

The line is part of the Distributed Biological Observatory, a system for the sharing of Arctic data started by Arctic oceanographer Jackie Grebmeier. These lines are mostly in the Pacific Arctic, with a few in the Canadian Arctic.

DBO sites. Taken from the DBO website.

Part of the beauty of these DBO lines (there aren’t any physical lines in the water – the ship travels in a line defined by a series of data collection points) is they add historical context. If multiple scientists take data from the same lines, that data can be compared over time with a few less variables. Scientists put their findings in a public database for greater community understanding of the area. As part of the CTD work, we’ve collected ADCP data (Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler – similar to sonar and used to measure water current velocities), some of which won’t be used by the scientists onboard but will be useful to others in the oceanographic community. This kind of collaboration for the greater good is one cool part of working in a remote place that spans international boundaries like the Arctic – ship time is valuable, and if one oceanographer can make use of her time to collect a little extra data for another oceanographer, more often than not she will.

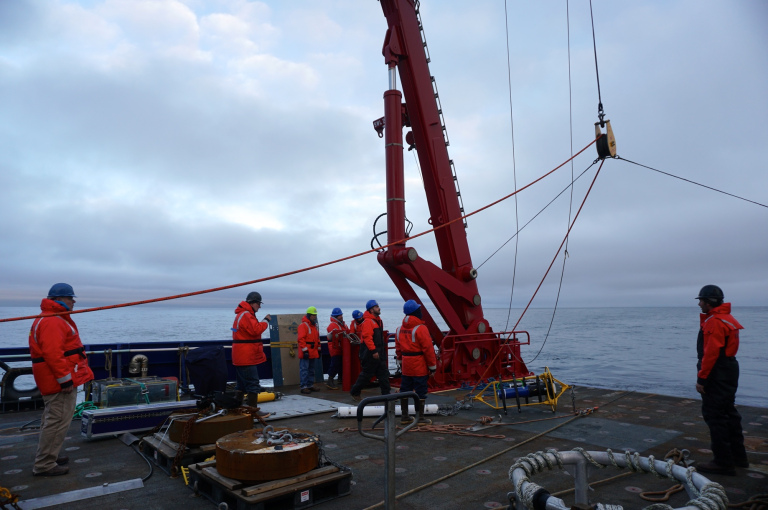

We also recovered and replaced a mooring this week. The mooring described in this video was put in on Wednesday, Sept 7.

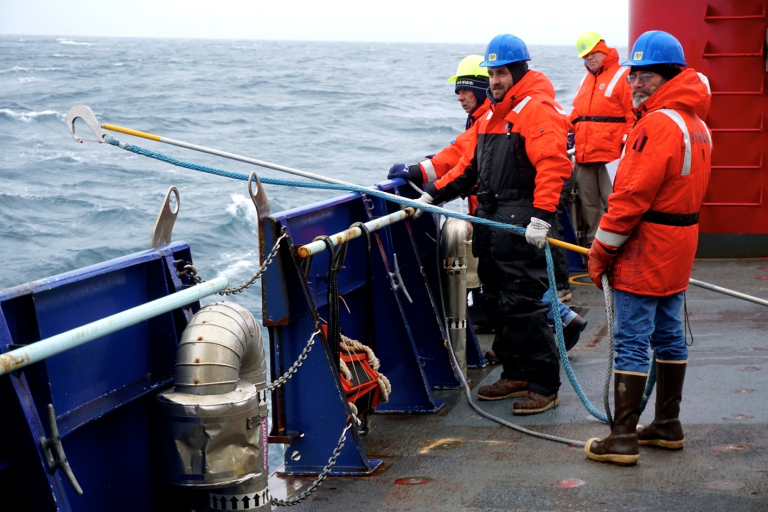

Some of the crew – John French, Paul St. Onge, Diego Mello, and Marshall Schwartz – ready for mooring recovery

Our journey along the DBO 6 line was bookended by forays into the sea ice. Our original plan was to take CTDs along six lines: DBO 6 (which allows us to compare shallow and deep data from the Beaufort Basin), DBO 5 (the traditional line goes across Barrow Canyon, but in order to avoid disturbing whales that might be near the shore, data collection was planned farther offshore), the Wainwright line, DBO 4 (on the Chukchi shelf in relatively shallow water) the Barrow/Hannah Shoal line, and the Icy Cape line. But the ice has prevented us from getting to DBO 5 and the Wainwright line, so we’re on our way to DBO 4.

Up next: Week 1 recap and our time in the ice.

— Kim Kenny is a freelance journalist who specializes in science writing and multimedia. This post was originally published on thedynamicarctic.wordpress.com

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.