7 April 2015

New study explains source of Earth’s mysterious ringing

Posted by Nanci Bompey

By Nanci Bompey

Scientists have come up with an explanation of why the Earth rings like a bell.

It’s long been known that earthquakes can cause the Earth to oscillate, or ring, for days or months, but in the late 1990s, seismologists discovered that the planet constantly vibrates at very low frequencies, even when there are no earthquakes. This ever-present background tremor can’t be felt by humans, but can be detected by sensitive seismic instruments.

Waves from the Johanna storm hitting the coast at Le Conquet, France in 2008. A new study finds that most of the Earth’s hum comes from the movement of long ocean waves over steep continental shelves.

Credit: Steven Lamarche

In the years since the discovery, scientists have come up with explanations for this continuous vibration. One theory suggests it’s generated by ocean waves moving in opposite directions. When the waves collide, they create very weak, “microseismic” waves that add up to a generalized ringing.

A group of French researchers have now tested this theory by using models to calculate how ocean waves could generate seismic waves. They found that opposing ocean waves could initiate a particular kind of seismic waves – those that take 13 seconds or less to complete one oscillation. But, when it came to even slower oscillating seismic waves, the theory did not hold up. That left seismic experts in a quandary, because it’s very slow waves, with periods greater than 50 seconds, that are at the heart of the planet’s bell-like resonance.

The researchers then turned to another theory that suggests the movement of ocean waves over the bottom of the ocean generates these slower oscillating, very long waves. Long ocean waves can extend all the way down to the seafloor. As they make their way back and forth to the open ocean from the coast, these long waves travel over the bumpy ocean bottom. The pressure of the ocean waves on the seafloor generates seismic waves that cause the Earth to oscillate, said Fabrice Ardhuin, a senior research scientist at Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Brest, France, and lead author of the new research.

When the team plugged this theory into their models, they found that it could explain the longer microseismic signals, ranging from 13 seconds to 300 seconds. The researchers concluded that instead of one theory explaining all of the microseismic activity, both theories are needed – one to explain the shorter seismic waves and another to explain the longer seismic waves responsible for the Earth’s hum. They suggest that most of the hum comes from the movement of the long ocean waves over the steep continental shelves.

The team published their results in a new study in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

“We have made a big step in explaining this mysterious signal and where it is coming from and what is the mechanism,” Ardhuin said.

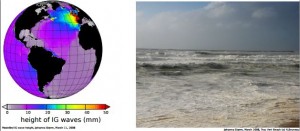

The graphic on the left shows the computed height of long-period waves during the Johanna Storm in 2008. The picture on the right shows waves at a beach south of Bordeaux, France, during the storm. The pressure of these long ocean waves on the seafloor generates seismic waves that cause the Earth to oscillate, according to a new study.

Credit: Fabrice Ardhuin

Understanding the Earth’s ringing could help scientists map the inside of the planet, Ardhuin said. The long, microseismic waves causing the resonance penetrate deep into Earth’s mantle, possibly to the planet’s core, so recording and understanding these waves could give scientists a much more detailed picture of the Earth’s structure, he said.

Ardhuin said understanding where these seismic signals are coming from also enables researchers to look for even fainter seismic signals. That could allow scientists to better detect faint earthquakes far away from seismic stations or nuclear explosions, he said.

“I think it is a relief to the seismologists,” Ardhuin said of figuring out the source of Earth’s ringing. “Now we know where this ringing comes from and the next question is: what can we do with it.”

— Nanci Bompey is a public information specialist/writer in AGU’s public information office.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

Is it a ringing or a hum, or both?

Also caused by ocean waves hitting the sea bed.

Scientists Track Down Source of Earth’s Hum | WIRED

Aug 7, 2009 – You can’t hear it, but the Earth is constantly humming. And some parts of the world sing louder than others. After discovering the mysterious .

http://www.wired.com/2009/08/hummingearth/

Good question. Both are just non-scientific terms describing the same thing.

Anybody know what frequency Earth’s ringing was at?