3 April 2014

Cutting back on refrigerants could drop greenhouse gas emissions

Posted by abranscombe

By Alexandra Branscombe

WASHINGTON, DC – Phasing down powerful climate-damaging greenhouse gases used in refrigerators and air conditioners could prevent the equivalent of up to three years of worldwide carbon dioxide emissions from being released into the atmosphere, according to a new study.

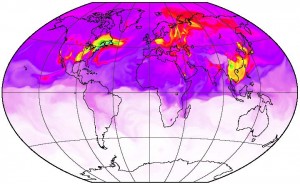

Models of the atmosphere can be used to simulate how synthetic greenhouse gases are transported around the globe. The yellow, green and blue areas show the highest concentrations of climate-warming Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) near areas with the highest emissions. Scientists used these models in combination with measurements of trace gases to calculate the amount of HFCs in the atmosphere, according to new research.

Credit: M. Rigby

Research accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, calculates the environmental impact of phasing down hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs, under the Montreal Protocol. The landmark 1987 agreement phased out the use of ozone-depleting refrigerants, like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), leading to increased used of replacements that include HFCs.

A proposed amendment to the Montreal Protocol would phase down the use of atmosphere-damaging HFCs. Although carbon dioxide is still the main greenhouse gas driving climate change, HFCs and a related chemical family, hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), are causing the largest increase each year in greenhouse gas warming, according to the study.

If new global regulations reducing use of long-lived HFCs are adopted, it could prevent an equivalent of 90 gigatons of global carbon dioxide emissions. It’s as if “we could avoid adding up to another three years of [carbon dioxide] emissions into the atmosphere,” explained Matt Rigby, co-author of the study and a research fellow at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom.

“Per ton of emissions [HFCs and HCFCs] are more potent greenhouse gases,” than carbon dioxide, Rigby explained. These gases are present in the atmosphere at parts per trillion—equivalent to a spritz of cologne diffused throughout a football stadium—but they are “very good” at trapping radiation that heats the Earth, he said. They also last for a long time in the atmosphere and accumulate as their use continues.

In 2007, an amendment to the Montreal Protocol accelerated a plan to phase-down HCFCs, and more recently the U.S. is working with other countries to amend the agreement to reduce the production of long-lived HFCs, which are powerful greenhouse gases. The agreement does not address shorter-lived HFCs, which last less than a year. In a related development, President Obama and President Xi of China agreed in June 2013 to work together to phase down the production of climate-damaging HFCs.

The Mace Head Advance Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE) station in Ireland. The station began taking atmospheric measurements for AGAGE operations in 1987. Scientists studying HFC emission trends used the world-wide AGAGE network, including the Mace Head station, to gather decades of data that contributed to a recent study accepted for a publication in Geophysical Research Letters.

Credit: AGAGE

Rigby and his colleagues used data collected from the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE), a global observing system sponsored by NASA that measures trace gases in the Earth’s atmosphere, to look at planet-wide emissions of 25 synthetic greenhouse gases from 1978 through 2012.

The researchers then mapped out how the atmosphere might change under two scenarios: if nations continue to emit these long-lived HFCs at increasing rates, or if they adopt new HFC regulations under the Montreal Protocol.

If HFC use drops, “it gives us a little extra time,” said Steve Montzka, a research chemist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Boulder, CO, who was not involved in the research.

He explained that cutting HFCs may seem negligible given their small, current climate influence compared to carbon dioxide. But addressing long-lived HFC emissions now will ensure that the gases don’t become a significant contributor to greenhouse gas warming along with carbon dioxide in the future, which has been suggested as a real possibility, Montzka said.

Rigby said accurately predicting future amounts of HFCs in the atmosphere is difficult, because some countries may underreport emissions of these gases and many countries are not required to report emissions at all.

Developed countries are required to report HFC emissions under the Kyoto Protocol, a 1997 international agreement that committed industrialized nations to lowering greenhouse gas emissions. However, the Kyoto Protocol has not been enforced beyond 2012, nor been updated to include developing countries, like China and India, said Ronald Prinn, a professor of atmospheric chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Mass., and a co-author of the new study. As a result HFC emissions reported by industrialized nations have leveled off in recent years, so unreported emissions are now dominating the overall rise in HFCs, Prinn said.

“For more than 50 percent [of HFCs] that we know are being emitted globally, we have no reports of where they are coming from,” said Rigby. “The methods of reporting emissions are flawed.”

– Alexandra Branscombe is a science writing intern in AGU’s Public Information department

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.