15 June 2012

Quiet Eyjafyallajökull littered with reminders of 2010 explosion

Posted by kramsayer

The Gígjökull glacier, on the flanks of Eyjafjallajökull, was the site of a day-long Chapman Conference field trip. The debris in the foreground is a new addition – before the 2010 eruption, it was a glacier lagoon, complete with floating icebergs. (Credit: Ramsayer)

GeoSpace is in Selfoss, Iceland this week, reporting from AGU’s Chapman Conference on Volcanism and the Atmosphere. Check back for posts on the science presented at the meeting, as well as field trips to nearby volcanoes and geologic features.

Eyjafjallajökull Volcano, Iceland — With lava bombs and glacial debris crunching under our feet, we hiked up to the Gígjökull glacier in a valley on the slopes of Eyjafjallajökull. Three years ago, icebergs floated at the base of this glacier, in the milky water of a glacial lagoon. But in April 2010, the volcano erupted forcefully beneath Gígjökull, causing torrents of melted water called jökulhlaups to surge down the valley and into the lagoon, carrying with them enough boulders and debris fill it up, displacing all the water.

“The only reason why you can actually walk across this now is because of the 2010 eruption,” said Thor Thordarson, a volcanologist with the University of Edinburgh, and native Icelander. “On the 13th of April 2010, this area was a lagoon, up to 60 meters (200 feet) deep … On the 15th of April, it looked like this. And that shows you how rapidly these things change.”

Thor Thordarson explains the explosive events of April 14, 2010, when Eyjafjallajökull erupted, sending ash into the air and torrents of melted glacier water and debris down its flanks. (Credit: Ramsayer)

Eyjafjallajökull, “the volcano that no one can pronounce,” as Thordarson noted, was the site of an all-day field trip Wednesday during the Chapman Conference on Volcanism and the Atmosphere, an AGU-sponsored conference which Thordarson co-organized. More than 100 geologists, climate scientists, guests and others boarded buses for a bumpy ride up to the glacier, fording fast-moving streams along the way.

The activity started on Eyjafjallajökull’s flanks on 20 March 2010, with fire fountains spewing along a fissure that lasted for several weeks.

“It was a very nice tourist eruption,” Thordarson said the evening before during a talk on Icelandic volcanism at the nearby conference hotel in Selfoss. He showed a slide of cars lined up by the volcano as people watched the natural fireworks.

Chapman Conference participants gather samples of ash from Eyjafjallajökull’s 2010 eruption, which disrupted air travel in Europe and beyond. (Credit: Ramsayer)

But that low-impact eruption was followed by a second event — the infamous summit eruption, which ejected ash into European airspace, and was quite unfriendly for tourists and travelers worldwide. That second phase started later, on 14 April, and lasted for 29 days.

The volcano was quiet during the tour, but the impacts of the eruption were clearly visible. Standing before the volcano at the base of its glacier, Thordarson gave a run-down of the dramatic events of April 2010, when magma under Eyjafyallajökull’s crater erupted beneath the glacier, melting some of the ice. That meltwater cascaded down the mountain, carrying with it tons of debris that filled up the lagoon.

Black lava chunks, specked with the pale green crystals of the mineral olivine, from of the 2010 eruption were mixed in with lighter colored glacially deposited rocks in the area where the field-trip participants stood.

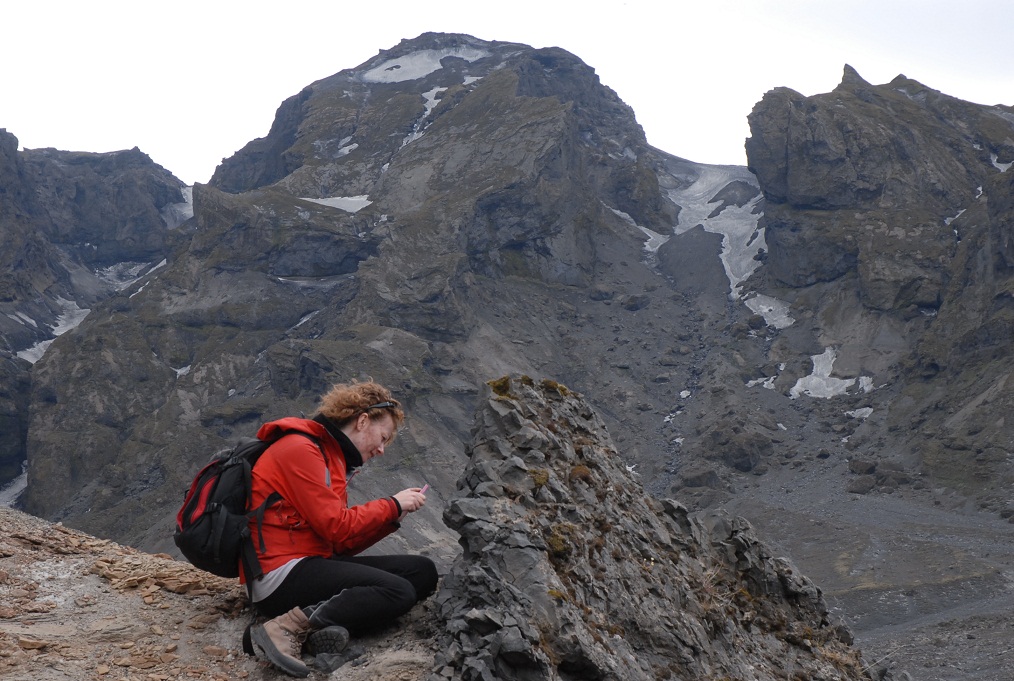

Herdis Schopka, with GFZ Potsdam, examines a rock formation during a field trip to Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull volcano. (Credit: Ramsayer)

Not much ash fell on that area, Thordarson said – it mostly drifted in the opposite direction, toward Europe. He led the group to a spot on the other side of the volcano, where he dug a shallow hole in the dirt, exposing a layer of dark ash several inches thick. As the scientists took pictures, several used trowels to carefully scrape samples into plastic bags and small canisters – at least one planned to compare the physical properties of the ash to other samples she collected elsewhere.

At another stop south of the volcano, near where the floods from the eruption emptied into the Atlantic Ocean, Thordarson dug into what had been a stream bed to show three layers of 2010 Eyjafyallajökull ash, flushed down after three different active events. At the top of two of the ash layers were small, rounded bits of light pumice smoothed by the force of the water.

The Seljalandsfoss waterfall (foss means waterfall in Icelandic) is south of Eyjafjallajökull, at a cliff that once formed the coastline. (Credit: Ramsayer)

The 2010 eruption was at one of its weakest phases when the winds were blowing toward the United Kingdom, Thordarson said prior to the field trip – so the disruption could have been worse. And Eyjafyallajökull is not Iceland’s largest or its most active volcano.

“Eyjafyallajökull is not going to be the last eruption to reach Europe,” Thordarson said. “So… we should continue studying Icelandic volcanoes.”

-Kate Ramsayer, AGU science writer

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

Hi, nice posting. But you named the waterfall wrong, you show the Seljalandsfoss and not the Skogafoss.

Changed it, thanks!

The final picture is of Seljalandfoss, not Skógafoss. Still a nice waterfall 🙂