26 January 2011

Ken Rasmussen is outstanding faculty!

This is from an e-mail I just got from Dr. Robert Templin, the President of Northern Virginia Community College, in reference to my colleague Ken Rasmussen:

Dear Colleague,

I am very pleased to share with you the news that Dr. Kenneth Rasmussen, Professor of Geology at the Annandale Campus, is a recipient of the Virginia Outstanding Faculty Award for 2011. This award, sponsored by Dominion and administered by the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia, is the highest honor bestowed by the Commonwealth on those who serve in higher education.

Students and colleagues readily attest to the vitality and quality that Dr. Rasmussen has brought to the study of geology and oceanography at NOVA since he joined the faculty in 1992. He has always believed that the best way to develop scientifically learned citizens is to involve them in field excursions along with hands-on laboratory experiences: “It keeps the science fresh and the teaching inspired, and it pays dividends in student development.” Twice annual cruises on the Chesapeake Bay allow students to use their own field observations to document real-time patterns in the health of the estuary. Whenever possible, he has involved students in his own extensive research projects, whether nearby at the Smithsonian Institution or halfway around the world at Lake Issyk-Kul in Kyrgyzstan.

To support his field courses and research, Dr, Rasmussen has secured grants from the National Science Foundation and the VCCS Professional Development Program, as well as receiving a NOVA Presidential Sabbatical. He has also been recognized as Faculty of the Year by the NVCC Educational Foundation and received the John H. Moss Award for Excellence in College Teaching from the National Association of Geoscience Teachers. He frequently finds ways to share within and beyond NOVA his passion for the earth sciences—and their criticality for a habitable planet—whether by providing Honors Options for students in his classes; making presentations to school children, teachers groups, and the Lifelong Learning Institute; or serving as a lecturer at George Washington University. He takes particular pride in knowing that a number of former students who have gone to major in geology or related fields are now serving as school teachers and college faculty members.

Ken Rasmussen is now in the company of eight other NOVA colleagues who have been recipients of the Virginia Outstanding Faculty Award. Please join me in thanking him for his distinguished service to the college and in congratulating him for this very special recognition.

Bob

Hearty congratulations to Ken for this worthy recognition!

The making of Baker’s Quarry

So here’s how I made that cake I showed you Monday.

Step 1: Collect the necessary ingredients:

(Nice job with the stitching, Photoshop… jeez!)

Step 2: Clear your schedule and start baking.

My first layer was to be “the basement complex” and so I wanted something marbled in appearance. Mixing chocolate-powder-stained batter with regular yellow batter was the method, and I threw chocolate chips into the mafic batter and “white baking chips” (such a descriptive name!) into the yellow batter, thinking they would be like metamorphic porphyroblasts. However, my batter was insufficiently viscous, and many of these chips sank down through the batter (approximating crystal settling perhaps?) to line the bottom of the cake. When I pulled it out of the oven, many of these chips stuck to the bottom of the baking pan:

And there were corresponding cavities in the base of my “basement” cake:

I baked a “basalt” (chocolate) cake next:

And then a yellow cake, and then a spice cake. The spice cake was where I started going crazy adding extra ingredients. I tossed in some walnuts and coconut and raisins, and then added in a series of “petrified trees” made of date logs. I just laid them down in three linear arrays atop the unbaked batter:

What happened next was interesting (to me, anyhow): the cake swelled as it baked, and the logs sank, and the top surface of the cake reached up and wrapped around the logs, sealing them inside, like the soft sediment deformation that results in ball-and-pillow structure. Here’s a view into the oven as this process was playing out:

Here’s the top of the spice cake stratum once it was done baking (the holes are me testing whether it was “done” with a chopstick). Notice the three “seams” marking where the date logs have sunk into the cake:

The bottom side of the spice cake is shown next. Note the three linear trends of the logs are visible here too, especially at the far left, where the force of the sinking log has pressed raisins and walnuts through the batter and up against the bottom of the pan:

Now it was time to start layering the cakes. Icing served to glue them together. Striving (as always) for authenticity, I added the crumbs and scrapings from the cake pan once the “basement” cake had been removed (see photo above). These represent sedimentary particles eroded off the basement, and marking the unconformity:

The basalt layer got slapped down next, but I immediately saw a problem — each cake was domed up in the middle, and stacking multiple cakes would result in them touching in the middle, but having the edges shorter than needed to reach the neighboring cake. Accordingly, I engaged in a little premeditated erosion:

With the domed top of the basalt removed, I iced it:

And added some sediment:

Likewise on up through the stack, reaching my log-bearing spice cake:

(The gird shape on top comes from me cooling it too soon upside-down on a cooling rack. It’s unintentional, though I suppose you might try to make the claim that it represents two orthogonal joint sets.)

Time to insert the pluton! While all this other stuff was going on, I had baked a circular (not rectangular) strawberry cake. I quartered it and stacked the quarters, producing a thick wedge with 90° of arc. Next, I would have to create some accommodation space. My way of solving “the room problem” was to cut out a corresponding sized-and-shaped piece of my stratiform composition:

The “pluton” of strawberry-flavored granite fit into this notch:

Here’s the cake, and it’s “missing piece,” chilling in the fridge while I prepared my next move:

I baked a batch of Rice Krispie treats, and carved out a meandering channel in them. I mixed up some blue Jell-O and tried at first to pour it into my channel. However, the porosity and permeability of the Rice Krispie treats would make an excellent aquifer, and the liquid Jell-O solution soaked right through. So I put it in the freezer to set up a bit more, and when it got to be a gelatinous goop, I poured it into the channel, where it stayed:

This was sealed to the top of everything else along a layer of homemade icing (basically, butter + sweet stuff), since by this time I had run out of the store-bought stuff. The finished product looked like this:

Rotated 90° counter-clockwise for another view:

Rotated 90° counter-clockwise for another view:

Rotated 90° counter-clockwise for another view:

Total casualties, 18 eggs:

A few hours later, we were off to friends’ house for dinner. I rode shotgun, cradling my cake in my lap:

I loved the way the upper surface looked in the sunlight. Ahh, the beauty of nature:

The final step was a big cut to reveal the cross-sectional structure…

And you know what it looked like after that…

——————————————————————————-

Got something to contribute to the Bake Sale? Remember that this Friday is the when the oven timer goes “ding!”

25 January 2011

Uncommon Carriers, by John McPhee

Over the weekend, hideously cold temperatures kept me indoors. I baked a cake, I went to see the new movie “True Grit” (excellent), and I read the 2006 compilation of John McPhee’s writing on transportation, Uncommon Carriers.

Like most everybody I know, I came to McPhee based on his geology writings — the quartet of books that were collectively republished en masse in 1998 as Annals of the Former World, an achievement which warranted a Pulitzer Prize. After that, I devoured his other books — I particularly dug Oranges (1967), The Deltoid Pumpkin Seed (1973), The Curve of Binding Energy (1974, the year I was born!), and Coming Into the Country (1977).

But I haven’t been as enthralled with McPhee’s more recent work. He profiled my friend and mentor E-an Zen in “Travels of the Rock,” included as the final essay in the 1997 collection Irons in the Fire. That held my attention, as did the other piece in that volume about forensic geology.

But in the new millennium, McPhee went through a fish phase and then got enraptured with transportation. (All along, he’s also been into sports, and that’s still true, but it’s the area of his writing that interests me the least, so I’ll say no more of it here.) I started subscribing to the New Yorker, where McPhee serves as a staff writer, in grad school in 2002, and over the subsequent 9 years of reading that magazine, I’ve seen his essays appear perhaps twice a year. Many of them have focused on transportation of one sort or another. It sounded, frankly, like a pretty dry topic, but then again, I would have thought there couldn’t be much to oranges, either.

So while I’ve read each of the essays in Uncommon Carriers when they were published in the New Yorker, I decided to re-read them as a collection. Grouped under a single cover and read in sequence is a different experience from reading them separated by year-long intervals. So what did patterns did I pick up on?

Each essay seems to mention the terrorist attacks of September 11th at some point. This strikes me as (a) germane to the subject matter, as truckers and barges and trains and planes are all now potential targets and weapons of terrorism. It’s relevant to the life of the modern day trucker or UPS router to have a clear idea of how terrorists might use them as part of a deadly plan. But no one seems to dwell on it. It also strikes me as (b) an evolution of McPhee as a writer. McPhee has been criticized by, among others, Edward Abbey for being too apolitical. Writing about oranges and Russian art and the Greenmarket is all well and good, Abbey implied, but why not use your status as a writer to right some wrong, to address an injustice or a way forward for a sticky issue. In fact, I think Abbey’s approach is clearly alienating to some, and McPhee is seen by many as politically “safe,” interesting without indulging in the argumentation or rhetoric which permeates just about everything else we read. So I think there’s definitely a place for adamantly apolitical writers. I think it’s to McPhee’s credit that he’s willing to let himself evolve a bit by, if not exactly grappling with the issues, then at least letting them appear in his writing.

Another thing that McPhee has been criticized for is his anonymity. His stories never really featured any kind of details about his own life or perspective. That changed a bit with The Founding Fish (2002), where he indulged in a lot of description of his shad fishing, and reached previously-unknown levels in Silk Parachute, a 2010 collection of essays which are united by the thread that they all invoke “McPhee the man” at some point. (It was when he was promoting Silk Parachute last April that I saw him speak at DC’s iconic bookstore Politics and Prose.) Point being: the guy is willing to change, to loosen up a bit, as he gets older and more secure in his reputation.

The other area where this manifests itself in Uncommon Carriers is in the topic of fossil fuel use and climate change. This is particularly true for “Coal Train” and “A Fleet of One, Part 2”. The first of these, “Coal Train,” is about a staggering enterprise — the world’s largest mine spawning the world’s largest train, transporting carbon captured by ancient photosynthesis halfway across America. It is the epitome of our energy infrastructure — enormous and unwieldy and impressive.

It begins with the mines themselves. McPhee focuses on Rocky Mountain coal, formed in large continental basins during the early Cenozoic. He is particularly interested in the Power River Basin of Wyoming. At the Black Thunder Mine, for instance, they are digging into Paleocene Fort Union Formation coal, with individual beds that are “eight to ten stories thick.” Current mining of these coal units fills 60 coal trains per day. Each of those 60 trains is 19,000 tons fully loaded, 133 cars full of coal. Some outliers are over two miles in length! 60 of these behemoths roll out of the Powder River Basin each day, bound for places like Georgia, where the coal is powdered and oxidized and the resulting heat is captured to heat water to turn turbines so that electrical power may be generated. It’s a long chain of events that results in Atlantans having the lights go on when they flip a switch. McPhee documents the amazing scale of the operation.

In spite of his extraordinary figures, there is probably enough coal in the Powder River Basin to last (at current rates of usage) for 250 more years.

McPhee must have had environmental sensibilities for a long time — why else would he profile David Brower (Encounters With the Archdruid, 1971) or write a book called The Control of Nature (1989)? But nowhere in these early books is any sort of judgment or political stance expressed directly by McPhee as narrator. In Uncommon Carriers, however, he states his positions a bit more baldly: Quoting economist Kenneth Boulding, he states, “Anyone who believes that exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.”

“A Fleet of One” is the title of the essays that open and close the Uncommon Carriers volume. They focus on a trucker named Don Ainsworth who lets McPhee ride shotgun for thousands of miles across North America. Ainsworth keeps McPhee’s pencil twitching over his notebook with a constant torrent of quirky witticisms and ego. It’s entertaining — Ainsworth’s style blends well with McPhee’s narration in the manner of Henri Vaillancourt’s, recorded by McPhee in The Survival of the Bark Canoe (1975). However, McPhee displays much more tenderness towards Ainsworth as a protagonist than he did towards prickly Vaillancourt.

For instance, McPhee suggests Ainsworth is praiseworthy for sleeping in a hotel room, as opposed to in his truck with the engine idling. In the winter and summer months, most truckers in the United States catch 40 winks while their engines turn over (zero miles per gallon) to provide energy to run the heater or the air conditioners in the cab. Says McPhee (p. 248), “You have not heard the sound of creature comfort until you have heard hundreds of huddled trucks idling through the night.” He does some math: “Two million trucks [the U.S. truck population] times three hundred days amounts to six billion gallons of diesel fuel per annum burned basically to keep truck drivers cool, to keep truck drivers warm, and to keep happy presidents content.”

Whoa – that’s a clear swipe at George W. Bush, a statement unique in its political chutzpah in my reading of McPhee. He’s not hiding his environmentalism under a bushel anymore!

A final note — at several points in Uncommon Carriers, McPhee gives points out connections to early work. “Coal Train” mentions crossing Nebraska’s Platte River at a spot near where McPhee collected a handful of pebbles in his forensic geology piece many years earlier. He also mentions passing a home in Wyoming of Floyd Dominy, a dam-booster for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the man who was arch-enemy to the Archdruid. If you’ve indulged in McPhee’s complete oeuvre as I have, these little tangents ring with a deep satisfaction.

Uncommon Carriers, by John McPhee

Over the weekend, hideously cold temperatures kept me indoors. I baked a cake, I went to see the new movie “True Grit” (excellent), and I read the 2006 compilation of John McPhee’s writing on transportation, Uncommon Carriers.

Like most everybody I know, I came to McPhee based on his geology writings — the quartet of books that were collectively republished en masse in 1998 as Annals of the Former World, an achievement which warranted a Pulitzer Prize. After that, I devoured his other books — I particularly dug Oranges (1967), The Deltoid Pumpkin Seed (1973), The Curve of Binding Energy (1974, the year I was born!), and Coming Into the Country (1977).

But I haven’t been as enthralled with McPhee’s more recent work. He profiled my friend and mentor E-an Zen in “Travels of the Rock,” included as the final essay in the 1997 collection Irons in the Fire. That held my attention, as did the other piece in that volume about forensic geology.

But in the new millennium, McPhee went through a fish phase and then got enraptured with transportation. (All along, he’s also been into sports, and that’s still true, but it’s the area of his writing that interests me the least, so I’ll say no more of it here.) I started subscribing to the New Yorker, where McPhee serves as a staff writer, in grad school in 2002, and over the subsequent 9 years of reading that magazine, I’ve seen his essays appear perhaps twice a year. Many of them have focused on transportation of one sort or another. It sounded, frankly, like a pretty dry topic, but then again, I would have thought there couldn’t be much to oranges, either.

So while I’ve read each of the essays in Uncommon Carriers when they were published in the New Yorker, I decided to re-read them as a collection. Grouped under a single cover and read in sequence is a different experience from reading them separated by year-long intervals. So what did patterns did I pick up on?

Each essay seems to mention the terrorist attacks of September 11th at some point. This strikes me as (a) germane to the subject matter, as truckers and barges and trains and planes are all now potential targets and weapons of terrorism. It’s relevant to the life of the modern day trucker or UPS router to have a clear idea of how terrorists might use them as part of a deadly plan. But no one seems to dwell on it. It also strikes me as (b) an evolution of McPhee as a writer. McPhee has been criticized by, among others, Edward Abbey for being too apolitical. Writing about oranges and Russian art and the Greenmarket is all well and good, Abbey implied, but why not use your status as a writer to right some wrong, to address an injustice or a way forward for a sticky issue. In fact, I think Abbey’s approach is clearly alienating to some, and McPhee is seen by many as politically “safe,” interesting without indulging in the argumentation or rhetoric which permeates just about everything else we read. So I think there’s definitely a place for adamantly apolitical writers. I think it’s to McPhee’s credit that he’s willing to let himself evolve a bit by, if not exactly grappling with the issues, then at least letting them appear in his writing.

Another thing that McPhee has been criticized for is his anonymity. His stories never really featured any kind of details about his own life or perspective. That changed a bit with The Founding Fish (2002), where he indulged in a lot of description of his shad fishing, and reached previously-unknown levels in Silk Parachute, a 2010 collection of essays which are united by the thread that they all invoke “McPhee the man” at some point. (It was when he was promoting Silk Parachute last April that I saw him speak at DC’s iconic bookstore Politics and Prose.) Point being: the guy is willing to change, to loosen up a bit, as he gets older and more secure in his reputation.

The other area where this manifests itself in Uncommon Carriers is in the topic of fossil fuel use and climate change. This is particularly true for “Coal Train” and “A Fleet of One, Part 2”. The first of these, “Coal Train,” is about a staggering enterprise — the world’s largest mine spawning the world’s largest train, transporting carbon captured by ancient photosynthesis halfway across America. It is the epitome of our energy infrastructure — enormous and unwieldy and impressive.

It begins with the mines themselves. McPhee focuses on Rocky Mountain coal, formed in large continental basins during the early Cenozoic. He is particularly interested in the Power River Basin of Wyoming. At the Black Thunder Mine, for instance, they are digging into Paleocene Fort Union Formation coal, with individual beds that are “eight to ten stories thick.” Current mining of these coal units fills 60 coal trains per day. Each of those 60 trains is 19,000 tons fully loaded, 133 cars full of coal. Some outliers are over two miles in length! 60 of these behemoths roll out of the Powder River Basin each day, bound for places like Georgia, where the coal is powdered and oxidized and the resulting heat is captured to heat water to turn turbines so that electrical power may be generated. It’s a long chain of events that results in Atlantans having the lights go on when they flip a switch. McPhee documents the amazing scale of the operation.

In spite of his extraordinary figures, there is probably enough coal in the Powder River Basin to last (at current rates of usage) for 250 more years.

McPhee must have had environmental sensibilities for a long time — why else would he profile David Brower (Encounters With the Archdruid, 1971) or write a book called The Control of Nature (1989)? But nowhere in these early books is any sort of judgment or political stance expressed directly by McPhee as narrator. In Uncommon Carriers, however, he states his positions a bit more baldly: Quoting economist Kenneth Boulding, he states, “Anyone who believes that exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.”

“A Fleet of One” is the title of the essays that open and close the Uncommon Carriers volume. They focus on a trucker named Don Ainsworth who lets McPhee ride shotgun for thousands of miles across North America. Ainsworth keeps McPhee’s pencil twitching over his notebook with a constant torrent of quirky witticisms and ego. It’s entertaining — Ainsworth’s style blends well with McPhee’s narration in the manner of Henri Vaillancourt’s, recorded by McPhee in The Survival of the Bark Canoe (1975). However, McPhee displays much more tenderness towards Ainsworth as a protagonist than he did towards prickly Vaillancourt.

For instance, McPhee suggests Ainsworth is praiseworthy for sleeping in a hotel room, as opposed to in his truck with the engine idling. In the winter and summer months, most truckers in the United States catch 40 winks while their engines turn over (zero miles per gallon) to provide energy to run the heater or the air conditioners in the cab. Says McPhee (p. 248), “You have not heard the sound of creature comfort until you have heard hundreds of huddled trucks idling through the night.” He does some math: “Two million trucks [the U.S. truck population] times three hundred days amounts to six billion gallons of diesel fuel per annum burned basically to keep truck drivers cool, to keep truck drivers warm, and to keep happy presidents content.”

Whoa – that’s a clear swipe at George W. Bush, a statement unique in its political chutzpah in my reading of McPhee. He’s not hiding his environmentalism under a bushel anymore!

A final note — at several points in Uncommon Carriers, McPhee gives points out connections to early work. “Coal Train” mentions crossing Nebraska’s Platte River at a spot near where McPhee collected a handful of pebbles in his forensic geology piece many years earlier. He also mentions passing a home in Wyoming of Floyd Dominy, a dam-booster for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the man who was arch-enemy to the Archdruid. If you’ve indulged in McPhee’s complete oeuvre as I have, these little tangents ring with a deep satisfaction.

24 January 2011

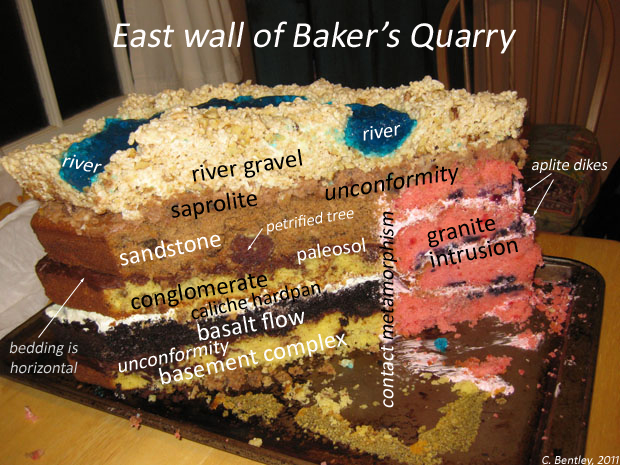

East wall of Baker’s Quarry

In the field last weekend, around snacktime, I crossed the border from Candyland into Baked Alaska. There, I encountered an excavation into the strata of the region, as a local patisserie was mining for ingredients. Their work had exposed a beautiful cross-section of the subsurface. I documented the occasion with my camera and some intense field work. Time was short, as mining operations were in full swing. For posterity, I reproduce here for my geobaking colleagues the east wall of Baker’s Quarry:

Here is an annotated version, based on my field notes (which, it must be admitted, were difficult to read due to smearing with chocolate icing):

The processes it took to produce this particular arrangement of rock types must have been as follows: First, an ancient episode of mountain-building produced the swirled gneisses of the basement complex. Mafic foliations of amphibochocolate, bearing porphyroblasts of Ghiradellite, strike predominantly to the northwest, though they are in places folded isoclinally about axes which plunge steeply to the northeast. Ion microprobe dating of the Ghiradellite reveals a crystallization age of a couple of months ago, with a metamorphic age of Saturday morning around 9am, plus or minus half an hour. We interpret this metamorphic age as indicating the orogenic activity accompanying the construction of the superconfectinent Pan-gea.

A period of erosion must have followed, for a pronounced unconformity is observed atop the basement complex. Mixed in with the icing there are coherent crumbs of the basement complex. Atop this unconformity is a layer of chocolatey basalt, including mafic xenoliths. Columnar jointing is absent from this layer, though there are curious structures which resemble marks left by a butterknife spreading frosting. We interpret this volcanism as decompression melting accompanying superconfectinent breakup and the opening of the Strudel Sea. An arid climate must have predominated in the time after the eruption of the basalt, for we observe a layer of white frosting atop it. This is interpreted as a caliche hardpan.

A polymictic, matrix-supported conglomerate is next in the sequence, with a channel lag deposit at its base. There, we identified raisins, walnuts, and baking chips of several varieties. The provenance of these inclusions is enigmatic. We interpret the unit as a series of vanilla-flavored mudflows and river deposits.

A rich brown paleosol is seen atop the conglomerate, indicating the passage of time, stabilization of base level, and temperate climate. A sandstone unit overlies the paleosol. This unit is distinctive not only for its spicy aroma, but also for the presence of petrified logs from the date tree. An oblique section through one prone date log is visible at the base of the Spicecake Sandstone formation as exposed halfway up the east wall of Baker’s Quarry. This species was prominent in fluvial margins and floodplains of the North American continent beginning in the Hersheyian epoch and persisting into the Carbohydratian, though they are significantly less common from the WillyWonkaian forward. Elsewhere, radiometric dating has established this range as 10:15am until 1pm. This constrains the depositional age of the Spicecake Sandstone to somewhere in that stretch of geobaking time, meaning that the strata beneath it but above the basement complex have a maximum age of 9am and a minimum age of 1pm.

Cross-cutting all the units hitherto described is a potassic granite pluton, itself crosscut by numerous subhorizontal dikes of aplite. It is a striking pink color, almost too pink to seem natural. We have dubbed it the Strawberry Granite. Though the contact shown in the east wall of Baker’s Quarry is subvertical, mapping of the pluton in the third dimension reveals a circular outcrop pattern. The presence of blueberries and red candy nuggets suggest the magma was perafruitinous in composition. A zone of contact metamorphism, marked by strawberry icing, surrounds the intrusion. Geochemical fingerprinting of xenoliths of dried strawberries in the cake suggest wall rock stoping, perhaps sourced from a nearby box of Paul Newman’s “Sweet Enough” cereal. The intrusion does not appear to be temporally associated with any regional deformation, and thus we interpret it as anorogenic.

A period of uplift and erosion followed, producing an unconformity surface marked by a thick zone of saprolite. A large proportion of coconut flakes may be found in this unit. The modern Jell-O River was established over this weathered surface, bringing in a large quantity of gravel from the nearby Sticky Fingers Mountains. Dominated by Rice Krispies, this river gravel deposit also includes white chocolate chips and walnuts. A cement of marshmallow has incompletely lithified this unit, but the river continues to meander through it. Somewhat amazingly, the river hasn’t yet poured down into the quarry to fill it. This may have something to due with the frigid temperatures at the time of my visit — the river’s flow appeared quite gelid.

Historical records indicate that quarrying operations began in earnest around 9:30pm, although there is anecdotal evidence of small scale nibbling, particularly in the Strawberry Granite, prior to that time. Though only crumbs were removed, a few locals reported their findings to others. Resulting hype and rumor-mongering built up public anticipation to a frenzied hum. When the echoes of dinner had faded, industrial-scale excavations began at Baker’s Quarry.

Mountaintop removal made short work of the resistant upper layers, and the multiple sweetrata were soon severely eroded, with the unfortunate effect of destroying the outcrop for future scientific investigation. I’m pleased to have had the chance to document the formations exposed there during their brief period of existence.

——————————————————————————-

Got something to contribute to the Bake Sale? Remember that this Friday is the when the oven timer goes “ding!”

22 January 2011

Let’s coin a name for this phenomenon

I didn’t mention it yesterday, but there was one other structure that I saw at my newest outcrop on New 55. This is it:

That’s a bunch of fractures. The broken rock is being altered by preferential fluid flow through the fractures. The fluid is not inert; it’s chemically active, and reacting with the rock. These reactions produce the color and weathering differences that you note in the previous images. (Notice how the cores of each block are more spheroidal than the original angular outer shape of the block defined by the fractures.)

We saw something similar at Baker’s Beach in California last month:

And of course, we saw something similar last May in Shenandoah National Park, Virginia:

And then there is this example from the USGS Library in Reston, Virginia:

I just wanted to put all these photos together in one place (this post) and ask what I should call this phenomenon? I feel like it needs a good, evocative geologic name. The last example is dubbed “boxwork,” but I’m not sure that name really captures what’s going on in the top three locations.

Do we need to coin a neologism? Any nominations?

21 January 2011

Friday fold: scenes from new 55

On Monday, driving back from a cross-country skiing trip last weekend in West Virginia’s Canaan Valley, Lily allowed me to pull over to check out a previously-un-checked-out outcrop on the north margin of “New 55,” the pork barrel boondoggle spawn of Robert Byrd, late senator of West Virginia. This enormous road, far out of proportion to its actual usage, is simultaneously an environmental disaster and a superb collection of Valley & Ridge outcrops. It is rich in exposures of both primary sedimentary structures and deformational structures associated with Appalachian mountain-building. Like this one:

My photographer took a closer in shot, too:

Although I feel like I could have gotten some more direction as to the exact position of my arms. Fortunately, I’m such a pro at Photoshop that I can easily resolve such issues in post-production:

…Ahh, yes. That’s better…

Today’s fold is an asymmetric plunging anticline in the Hampshire Formation, strata laid down in the Kaskaskia Sea, a late Devonian to early Mississippian epeiric sea that covered much of North America while the Acadian Orogeny was playing out on the “east” coast. The young mountains shed off sediments, which “west”ward flowing rivers carried to the Kaskaskia. There the sediments accumulated, layer upon layer.

During the late Paleozoic Alleghanian Orogeny, convergence with Africa buckled up the strata of the Valley & Ridge province, folding and thrust faulting them.

Here’s some lovely ripple marks a few meters away, formed as Kaskaskia wavelets sloshed about, arranging little ridges of sediment:

Can you tell what I’m pointing at here?

It’s a patch of slickensides on the bedding plane, indicating that these sedimentary layers of sandstone acted as relatively stiff, coherent sheets during deformation, and interleaved layers of shale slipped and slid, allowing the layers to shift a bit relative to one another, and allowing the overall folding to occur. This shifting over pre-existing mechanical layers (the bedding planes) creates a palimpsest of structure: tectonic structures superimposed on primary structures.

The bedding and ripple marks are late Devonian; the slickensides formed during shortening of the Valley & Ridge province and the thickening of the young Appalachian mountains during the late Paleozoic. Let’s call them Pennsylvanian in age. It offered me a nice little geological “time-taste” to break up a long drive home. A snack of perspective…

Bonus structure! Pencil cleavage:

Happy Friday, everyone!

20 January 2011

A warm, glowing feeling

Just got this in an email:

“Hi professor Bentley,

This is [redacted], I had you for Geology last Spring. I just wanted to email you to first off, thank you, and second off, to ask some questions. Before I took your class Science was my worst subject , and I did everything to avoid taking it. I ended up needing it so I chose Geology since i was very slightly more interested in the earth rather than how the human body works. To this day I recommend you and your class to everyone I know because it was the best class I have ever taken. I looked forward to attending your class because you made it so interesting and ever since your class, Geology interests me so much and all of the places you traveled are now places I dream to travel one day. I actually took my family to the Billy Goat Trail on mothers day and taught them all of the things you taught me. You have been a huge inspiration to me and I am now looking into majoring in Geology, which is the last thing I ever would’ve imagined. So I wanted to thank you.”

: )

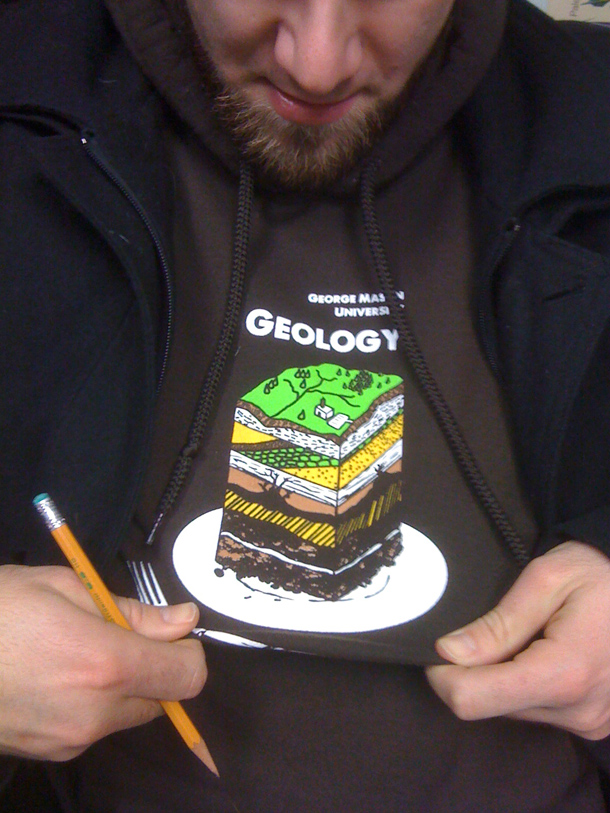

Reminder: AW#30, the Bake Sale

This is a friendly reminder that you have one more week to prepare your brownies, cakes, puddings, eclairs, gumballs, gobstoppers, and cookies for the Accretionary Wedge Bake Sale. The deadline for the submission of entries is a week from tomorrow, next Friday, January 28. Leave a link in the comments here, or at the original post.

As an example of a coincidence that reinforces the “Bake Sale” theme, here’s an iPhone photo of a former student (let’s just call him “N.”) which shows the George Mason Geology department’s new student-produced sweatshirt pattern:

Hmmm. That looks familiar…

Happy baking!

19 January 2011

Video book review III: evolution

Amazon links to the five books mentioned:

Your Inner Fish by Neil Shubin

Why Evolution is True by Jerry Coyne

The Greatest Show on Earth by Richard Dawkins

(and we gave a shout out to the superb The Ancestor’s Tale by Richard Dawkins, also)

(the video with the giraffe neck dissection)

Evolution: the Story of Life on Earth by Jay Hosler, Kevin Cannon, and Zander Cannon

Free PDF preview of Chapter 3, “E is for Extinction”

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.