24 June 2016

Big Becomes Great

Posted by larryohanlon

This is the latest in a series of dispatches from scientists and education officers aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s R/V Falkor, currently on an expedition measuring nutrient fluxes to the South China Sea. Read more posts here, and track the Falkor’s progress here.

Ajit Subramaniam defines himself as a Tactile Oceanographer: “I need to throw up in the water before I can understand it,” he jokes. That is why he is very pleased with R/V Falkor and how stable she has been during this expedition, his chronic seasickness has not been an issue and he has been able to concentrate on what he loves. Ajit loves the ocean and he loves rivers.

Ajit studies great rivers. As in Amazon great. He has studied the South American giant extensively, so what brought him here? After all, the Amazon is some 13 times larger than the Mekong. “Each river is different.” He says, “Just because you’ve studied one, it would be a big mistake to think you know them all. The Mekong is fascinating because it is in transition. It is changing extremely rapidly, right in front of our eyes.”

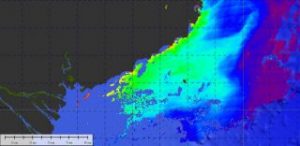

One of Dr. Subramaniam’s tasks on the cruise is processing satellite data to locate the river’s plume.

Credit: SOI/Ajit Subramaniam

Leaving a Mark

There is some debate on what makes a river great. Is it its length? Its width? Ajit always thought it was more a matter of water volume, but after years of observing river plumes, he now opts for permanence. A river is great when its discharge has a detectable impact on the ocean; when its plume remains unmixed or fairly stable for a considerable period of time, without losing its idiosyncrasy.

For a few months a year, the Mekong becomes a great river. A seasonal offshore jet transports the plume well offshore and into the open waters of the South China Sea, where it mixes with seawater and has a clear impact on the ocean’s chemistry and biology. “These are fascinating waters. Did I find anything interesting or unexpected? Almost every day,” he reflects now that the expedition is coming to an end.

The experts onboard have found every chemical element and microorganism they had set to study. But the reasons behind their distribution and abundance remain mysterious. Ajit hopes the team is able to process a meaningful amount of the data collected in this cruise before coming back for a second time, when the monsoon season will be in full swing and the findings will surely be different.

Aging Gracefully

Ajit compares the study of nature with sketching a drawing: Every stroke adds to the picture, but if you don’t step back every now and then and examine the whole, you risk losing the necessary perspective. Just like a drawing needs distance to come together (or a scientist needs to step back and rethink the theories in order to answer questions) so do river plumes need room to mature and age gracefully.

When a great river plume enters the ocean it will change steadily over a period of time. Ajit calls this process “aging.” A river plume will deliver an initial pulse of nutrients, but the water will be very murky. The fresh water’s particles will need time to settle down so that organic matter can start mixing and so light can penetrate deeper. This way phytoplankton will start growing and chemical transformations will begin to take place via microbes and bacteria. Anthropogenic influence is tampering with this natural development, and Ajit worries that we might not be allowing the Mekong River plume to age gracefully.

Ajit and the other scientists onboard conduct their last experiments and begin to prepare to come back home. After studying data at their home institutions, they will come back and conduct the second leg of the Mekong Impact expedition. The ocean will not be as calm, and even the steady R/V Falkor may not be able to spare Ajit the familiar nausea of rough waters. But still he will return, lured by the Mekong’s metamorphosis from ‘Big’ to ‘Great.’

This post originally appeared on the Schmidt Ocean Institute blog.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.