18 March 2016

New findings from the New Horizons mission show Pluto is ‘really crazy’

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

By Rebecca Fowler

This is part of a new series of posts that highlight the importance of Earth and space science data and its contributions to society. Posts in this series showcase data facilities and data scientists; explain how Earth and space science data is collected, managed and used; explore what this data tells us about the planet; and delve into the challenges and issues involved in managing and using data. This series is intended to demystify Earth and space science data, and share how this data shapes our understanding of the world.

Whether or not you believe Pluto should be called a planet, you should still be awed by the initial findings from the data the spacecraft New Horizons collected during its flyby of the dwarf planet last July.

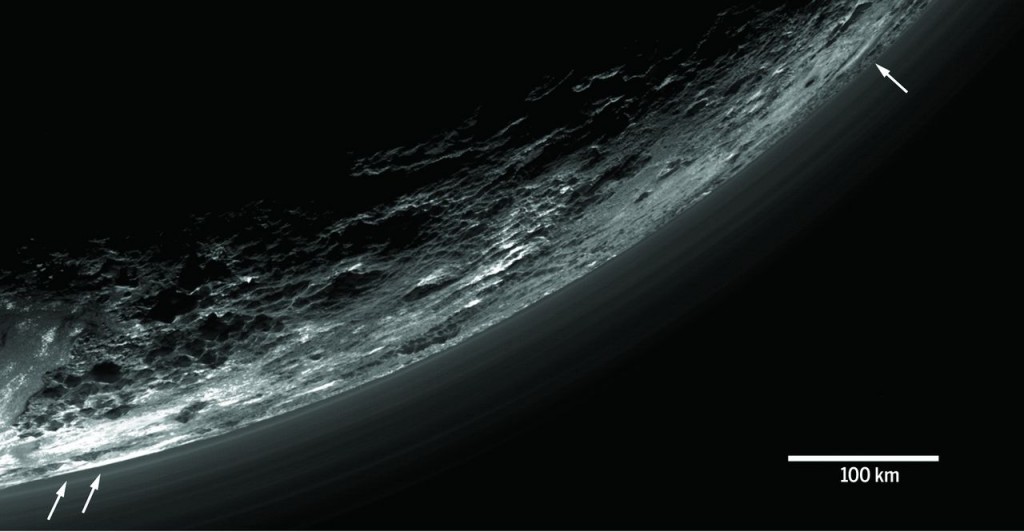

Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera (MVIC) image of haze layers above Pluto’s limb.

Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/AAAS/Science

The seven science instruments aboard New Horizons gathered nearly 50 gigabits of data on the spacecraft’s digital recorders. Much of this data is still streaming back to Earth, but preliminary data and observations were published this week in the journal Science.

The series of five papers describe the landscape and atmosphere of Pluto and its moons—icy, full of unusual features and nitrogen-dominated—the details of which amazed even the New Horizons’ scientists. Bill McKinnon, an astrophysicist at the University of Washington in St. Louis and deputy lead of the New Horizons Geology, Geophysics and Imaging team told Popular Mechanics, “[Pluto] turned out to be really crazy.”

If you’re not up for reading all five papers, NASA compiled a Letterman-style list of the top nine discoveries reported in Science; The New York TImes also published a summary of the findings and numerous stunning photos from the mission.

Many mysteries about Pluto remain. Once available, the rest of the data gathered by New Horizons will help to resolve some of these—and also be full of surprises.

— Rebecca Fowler is a science communicator and the Director of Communications and Outreach at the Federation of Earth Science Information Partners (ESIP).

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.