6 July 2008

I’ve got the Blue Ridge Blues (Quartz, of course)

Posted by Jessica Ball

After realizing that I hadn’t been camping for more than a year (yikes!) I immediately jumped on an opportunity to help my undergrad adviser with some fieldwork in the Blue Ridge last weekend. It was great fun to work with all the old hands in the department again, although bushwhacking through tick-infested thornbushes was not my favorite part of the weekend. (Not to mention that making an eight-hour trip up to New York immediately after two days of intense hiking was, to say the least, a bad idea.) Anyway, in examining the basement rocks of the Blue Ridge, we came across a lot of blue quartz. Blue quartz is common in the granites and granitoids out there, and it’s not unusual to come across large veins, most often in the middle of cow pastures. (Cows can be very good at exposing outcrops, but they also do their best to…ahem…cover them up again.)

Blue quartz has been found in Texas, India, Norway, and up and down the East Coast of North America from Rhode Island to South Carolina – mainly in the Blue Ridge. The examples I’ve seen have all been in the Old Rag granite, a Grenvillian-age (900-1600 Ma) coarse-grained granite that crops out often in Shenandoah National Park, and especially at Old Rag Mountain. (For a really good photo of Old Rag granite, look at Callan’s Geology of Shenandoah National Park page.) The Virginia Division of Mineral Resources publishes a quarterly called Virginia Minerals, and the best description I can find of Old Rag blue quartz is in the May 1981 issue. (The online copy is, sadly, in black and white, so it’s impossible to admire the quartz, but a 2002 Virginia Minerals article about the VDMR’s rock garden has a nice color photo.)

Blue quartz is, mineralogically speaking, pretty much like other kinds of quartz, but there are a few significant differences. The Virginia Minerals article says that

The uniqueness of blue quartz is due to properties that are uncharacteristic in ordinary quartz, opalescence, chatoyancy, and asterism. In addition, all blue quartz specimens are highly fractured and contain inclusions of rutile or other minerals.

Blue quartz has an opalescent or “waxy” (according to them) luster, which is changeable (“chatoyant”) depending on the light. Asterism is defined as the “illusion of a star-like figure” in a mineral, and seems to show up in photomicrographs of blue quartz.

There are several things that can cause quartz to look blue. The first is the presence of inclusions that scatter visible light in the blue part of the spectrum – usually zoisite, tourmaline and rutile. The blue color may also come from closely spaced, subparallel microfractures, which are found in all blue quartz samples. Finally, it has been suggested that the presence of titanium (in the form of rutile or ilmenite) could cause the blue color, although there are specimens of blue quartz with no titanium, and quartz of different colors that contains large amounts of titanium.

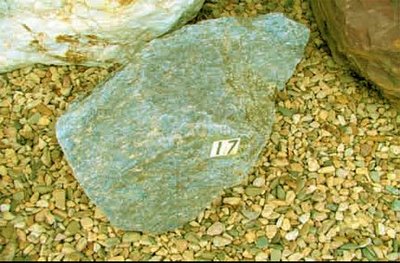

Here’s the photo from a 2002 Virginia Minerals (from the rock garden in front of their building in Charlottesville):

On the “woo” side of things, blue quartz, apparently, helps balance the lower and higher chakras, brings a sense of order and courage to life, releases fear, and boosts creativity and expression. It also brings mental clarity, helps one see and accept reality, lifts depression, reduces stubbornness and emotional tension, and enhances spiritual development.

Wow, really? Mine must be broken, because my living space is still a mess, I’m stressing about writing a paper and moving to a different state, I have to deal with obnoxious mood swings every month, and I haven’t seen a single indication that I’m less stubborn than I was when I picked up the stuff. Stupid defective minerals. The Old Rag granite owes me a refund. 😉

References:

Wise, Michael A., 1981, Blue Quartz in Virginia: Virginia Minerals, v. 27, no. 2, p. 9-12.

Marr, John and Sites, Roy, 2002, A Guide to the Educational Rock and Mineral Garden: Samples of Virginia’s Geological Diversity: Virginia Minerals, v. 48, no. 2/3, p. 15.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Yes, but does it do dishes? “chatoyant” — what a great word.

I love blue quartz! Great post. And I could use a little mental clarity, too. 🙂

I’ll be traveling around New England later this month. I got to keep an eye open for this stuff, which I never saw when I was at the U of New Hampshire.

Hi, nice blog! I see you are talking about Titanium Blue here. I should say that at the present time Titanium Blue offers a wide variety of earrings, bolos, rings, bracelets, ear cuffs and money clips. Titanium Blue is headquartered in Grass Valley, California. I learned about the company when I posted a complaint against another jewelry manufacturer on this great site http://www.pissedconsumer.com.

Hi Jessica, thanks for the write up on VA blue quartz. You mentioned some causes for the blue color for all blue quartz. For the quartz in VA what is the main cause of the blue. Just found a nice piece close to the Old Rag Mt area. What is the source of the blue for blue quartz in that area. thanks

I live in northern Loudoun County, VA. We have a lot of blue quartz on our property. Some that we’ve found in our creek has rusty veins through it (iron pyrite?) Other specimens have mica flakes, and others have what appears to be gold dust.

Does anyone have any information about blue quartz occurring with iron pyrite or gold?

I have a huge sample (about 25 lbs.) of blue quartz I got from my cousin’s farm in the Blue Ridge mountains in Virginia when I was a kid (I’m 60 now) and I’ve taken it with me everywhere I go. 20 years in the Air Force = a lot of moving. It’s in my front yard right now.

Hi! I know this was a long time ago but hoping you might get this! I live in Bristow & i would love to get a few blue quartz! I just found out that Virginia has a lot of quartz & I’ve bought & found white quartz. I havent done it yet but I want to make a small rock garden in my yard. I have to get a few more varieties before I do it. Pls respond & we can figure out how to connect if you’re willing. tks!

Are there any local places in Loudoun we could go dig for this? I’m sure my son would love it!

Good question! It can be found in granite, so anywhere that shows up on this map as “Porphyroblastic metagranite” would be a possibility. https://pubs.usgs.gov/imap/2553/pdf/LoudounCounty.pdf

I live in eastern WA and recently hiked in the North Idaho panhandle area & found a cutout, which revealed (with a few whacks of our pickaxe) beautiful blue quartz. At least, that’s what it looks like. Finding your website is SUPER helpful because what I’ve found looks & sounds by description just like blue quartz! Pleased I’ve found “confirmation,” although North Idaho isn’t listed as a place it can be found. I found plenty!