20 September 2019

This is an ex-eruption!

Posted by Jessica Ball

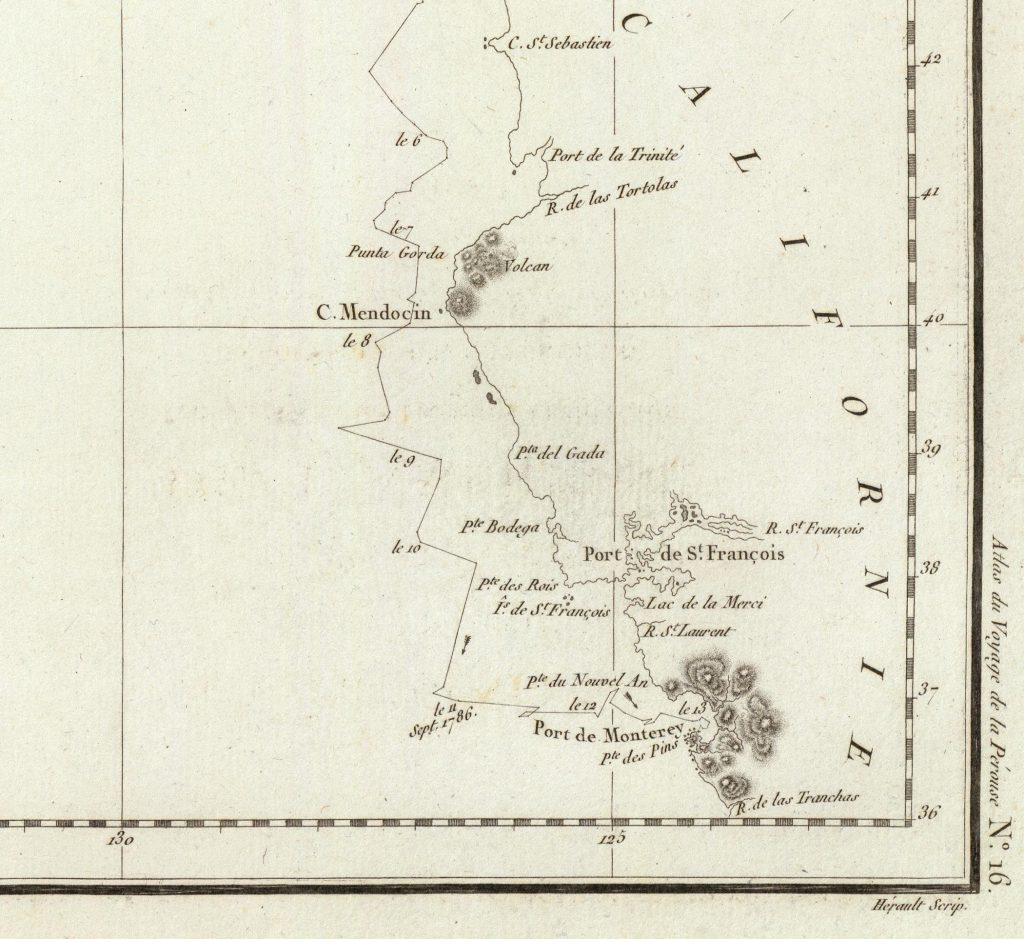

A portion of the 1797 map of the La Perouse expedition, in which a “Volcan” is placed on Cape Mendocino (noticeably rather far away from Mount Shasta’s actual location to the east and north.) Map courtesy of the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

Recently, as chronicled in Scientific American, I was involved with amending the eruptive record at California’s Mount Shasta to remove an eruption that was supposedly seen by a French mapping expedition in 1786. USGS researchers had already been puzzling over it for years – evidence was slim, since the area was already prone to forest fires and there was nothing in the geologic record to suggest that it happened. William C. Miesse, a historian at the College of the Siskiyous, had already compiled an extensive paper trail to track the evolution of the dubious eruption. The trail, it turned out, led to on one suspicious log record from an 18th-century cartographic expedition and a vague conclusion in a 1930 article by R.H. Finch in “The Volcano Letter”.

The recent change in the Smithsonian’s Global Volcanism database to “Discredited” was the final nail in the coffin for Shasta’s eruption of 1786. Now, being able to put “Volcano killer” on your resume is certainly a fun aspect of improving the Global Volcanism Database, as Janine Krippner knows. I can only manage “Eruption eraser” with the help of longtime researchers, but even that is nothing to sneeze at.

But why is that something to aspire to?

One of the big goals of geologic mapping at volcanoes is to come up with an eruption history. In mapping, we record what type of rock was being erupted at a particular time, with the help of geochronology (usually direct radiometric dating of the rock or carbon dating of plant material caught up in the eruption). This helps us figure out what a volcano was doing at different points in its evolution, how it grew and fell apart and behaved, what was going on its plumbing, and how often it erupted.

All of these are potentially things that a volcano could do again in the future, and that’s why eruption histories are crucial to assessing future hazards at volcanoes. If we know what a volcano did in the past and how often it happened, we might be able to say something about when and how it can erupt in the future. Eruptions in historical times (whatever that span may be in any given region) are particularly important, because they’re probably representative of a volcano’s current phase of activity.

So what does it matter if a recorded but unconfirmed eruption is in a volcano’s eruption history data? Well, for one thing, it irritates the heck out of the scientists who study that volcano… But joking aside, it can affect things like eruption likelihoods and bias observations of the volcano’s level of activity. Someplace that hasn’t had an eruption in living memory will seem that much more inert if its most recent eruption is no longer on the books. The trickle-down effects of this likely vary by location, but it could spur people to think that they need to do less preparation or that the volcano is ‘safer’ because its most recent eruption is older than people thought before.

On the other hand, there’s statistical methods of estimating eruption likelihood. These are more complicated than just taking into account the average time between eruptions; they also depend on how long it’s been since the last eruption, how many eruptions there have been overall, whether they cluster in time, and whether eruption style shows any patterns. Though in the grand geologic scheme removing one eruption may have little effect on patterns of eruptive behavior over a volcano’s lifetime, it might disrupt a clustering pattern or change the trend of eruptions over a shorter period.

But what it all boils down to is this: In some cases, bad data is worse than no data. As much as we’d like to have as much information as possible about a volcano, we also want that information to be as accurate as possible. If there’s no evidence for an eruption, then removing a reference to one that’s been propagated for decades is an important step in refining the eruption record that forms the basis for many scientific conclusions about a volcano.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Very cool. Thank you for sharing.