17 January 2011

Book review video 2

Books mentioned:

Bones, Rocks, and Stars: the Science of When Things Happened, by Chris Turney

Northwest Exposures: a Geologic Story of the Northwest, by David Alt & Donald Hyndman

Geology Underfoot in Death Valley and Owens Valley, by Robert Sharp & Allen Glazner

Stories in Stone: Travels Through Urban Geology, by David B. Williams

15 January 2011

Snowy detachment

I think snow can act as a nice analogue for larger-scale rock deformation. I explored this a bit last February, and I was reminded of it again last week, when I walked to my car one morning and saw this:

Notice how the slab of snow on the hood (“bonnet” for British readers) of my Prius has slid en masse down”hill,” leaving the top portion of the hood bare of snow, and crumpling up just above the license plate as it encounters the resistant obstacle of the bumper.

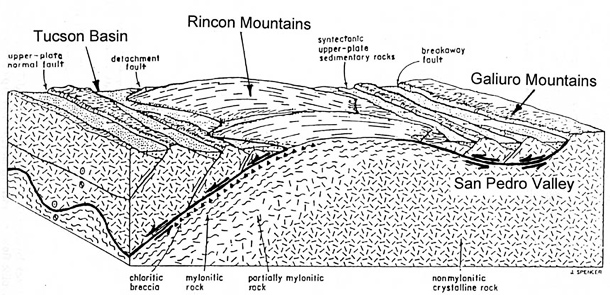

Naturally enough, I was reminded of a detachment fault, a low-angle “normal” fault, where the upper block slides down the face of the lower block, as in this example from Arizona:

[image source]

In my analogy, the snow is the upper block, and the Prius hood is the lower block. The contact between the two is the “detachment fault.”

Have you seen snow do anything neat like this lately?

14 January 2011

Friday fold(s): a few from Fossen

Last year, Haaken Fossen of the University of Bergen, Norway, published a full-color structural geology textbook called Structural Geology. So far, I think it is absolutely boffo. I’m reading it this semester as I teach structure at George Mason University, using my old standby text, George Davis and Stephen Reynolds’ Structural Geology of Rocks and Regions. I may switch to Fossen’s text next year. Certainly the imagery is enticing…

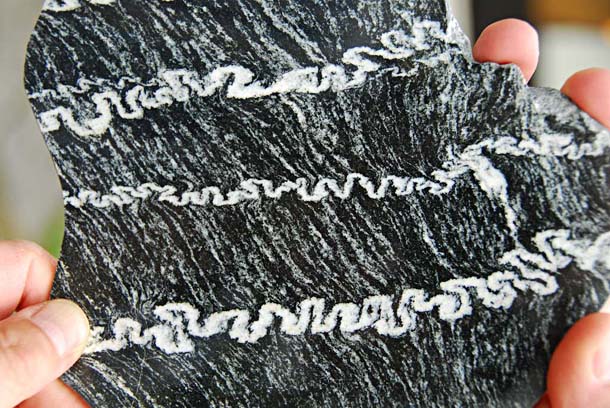

In exploring the online resources for the text, I was pleased to discover full-sized digital JPG files (600 dpi) for all the figures in the text. Nice! I was so taken with some of the fold images, that I e-mailed Dr. Fossen and asked him if I could feature a couple here as the “Friday fold.” He willingly granted me permission, and so I am pleased to present two eye-popping folds from his collection:

Folded banded iron formation with shale interbeds, exposed in a pavement near Soudan, Minnesota.

Buckled granitoid dikes within a gneiss from the Jotun Nappe, in the Norwegian Caledonides. The age of the folding is probably Grenvillian.

A full gallery of Fossen’s fold photos can be found at this link. If you click it, prepare to ooh and ahh for ten minutes or so.

Thanks to Dr. Fossen for permission to republish these images here.

13 January 2011

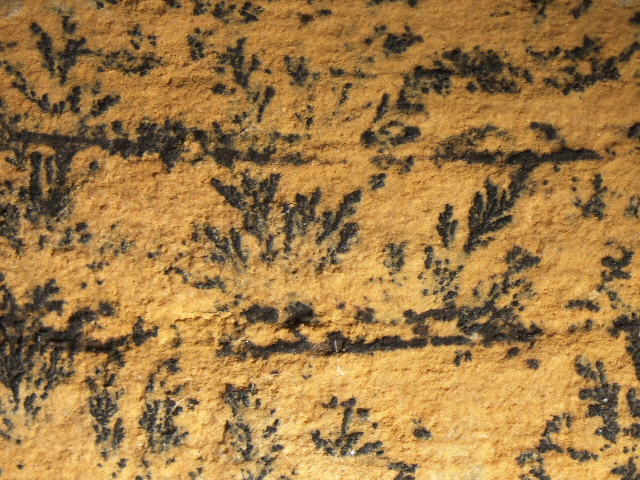

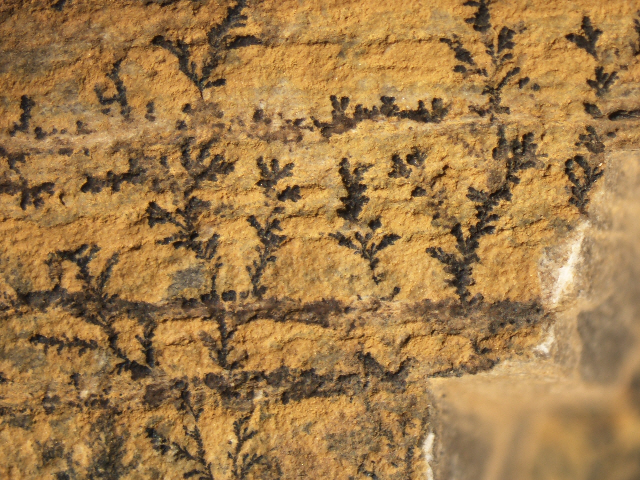

Delicious dendrites

Hopefully seasoned readers of this blog will remember this nice chunk of limestone with pyrolusite (MnO2) dendrites growing on its surface. I took some close-ups with my Nikon microscope a few weeks ago. Here they are; enjoy! The width of the field of view in each photograph is about 1.1 cm:

BTW, Mike likes dendrites, too.

12 January 2011

Experimental vs. historical science, and environmentalism

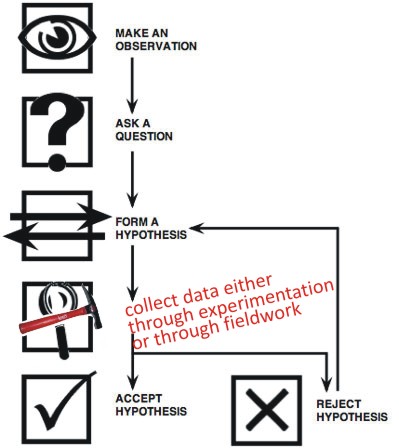

I propose that we replace this:

image source

With this:

Though some experimentation is an important part of the geological sciences, the historical geological record is written in nature. Experiments are any exercises we do where we control the variables and we watch how a system responds to our tweaks (e.g., rock deformation experiments, metamorphic reaction experiments under elevated P/T conditions, sedimentation rates in controlled chambers).

Experiments inform our understanding of nature, but nature comes first. Parts of our understanding may be decoded in a lab setting (e.g., isotopic dating, strain ellipse analysis, or groundwater chemistry), but the data are collected outside and must then be processed indoors. In geology, the big experiment has been run: its result is the planet we see before us. As archaeologists, cosmologists, and crime scene investigators must do, geologists use subtle clues to interpret the past.

Historical sciences have a different fundamental logic than experimental sciences, but they cannot be considered lesser merely because we cannot run experiments on the size and scale of the planet Earth’s 4.5 billion year history. Fixed laws are one thing, a sequence of events with contingency is another. Paul Hoffman has argued that a scientific approach to unraveling past events is geology’s greatest contribution to human thought.

Now that we have (maybe) entered the Anthropocene, we can run experiments of sufficient magnitude to be justly considered “experimentation on the Earth system,” where perturbations of planetary scale have been induced by agriculture, industrialization, and a human population rapidly approaching 7 billion. These are, empirically speaking, experiments on nature “her”self, experiments on the planet Earth. However, these experiments are hardly ideal, as (a) the variables are insufficiently controlled, (b) there is no control planet for comparison, and (c) we live in the “test tube” which hosts the experiment. This means that if the experiment produces civilization-destabilizing results, we have screwed ourselves over big time.

Human civilization is an independent variable in the Earth experiment, in that it has demonstrably altered the natural Earth system with novel conditions of quantifiable extent. Geoscientists may then watch to see how the Earth system responds (the “dependent variables”). What happens to the Earth system when we double CO2 in the atmosphere? NO2? CH4? What happens when we deplete the stratospheric O3 layer? Denude the soil? Chop down a third of all forests? Lower the oceanic pH by 0.7 units?

Image from New Scientist

These are all interesting questions, and I’m sure interested in the answers. I fact, I’d go so far as to say that it’s the most interesting set of experiments that humans have ever run, insofar as their unprecedented scale is concerned…

…But I also have a wee bit of trepidation living in the “test tube” which until now has been so homey and comfortable, …so homeostatic…

Anyhow, what’s my point? Historical and experimental sciences… we need both. As for the Big Experiment, I find it both fascinating and sketchy.

I’m not about to claim that the planet is in danger of being imminently rendered unfit for science, but maybe in addition to experimental science and physical science, we could also use a sense of empathy for the residents of our planet’s coastal plains, for the aragonitic-shell secreting organisms of the world ocean, and for the altitude-limited organisms who have reached the top of their local hill and can climb no further. Do these empathetic considerations deserve higher weight than the knowledge we stand to gain by letting the experiment run?

How do we balance this fascination with finally getting to run an (albeit imperfect) experiment with the fact we must live among the results?

11 January 2011

Blogger deserves GSA History Award

Join me in nominating David Bressan’s History of Geology blog for the Geological Society of America’s Mary C. Rabbitt History of Geology Award. To my knowledge, this would be the first time a blogger has won that honor. Every time I read one of David’s posts, I learn something new. I think it’s a wonderful service that he provides.

Who among you appreciate David’s efforts enough to support the application with a letter of support? Let me know who’s in. The nomination is due by February 1, so shoot me an e-mail if you want to contribute to the process. I might suggest that you emphasize how David synthesizes knowledge about the history of geology in order to promote understanding among a wide range of people using a free medium, the internet.

Thanks in advance!

10 January 2011

Call for posts: AW#30, the Bake Sale

Recent discussion of the geologically incorrect cake t-shirt at Threadless (earlier take-down here) and the actual baked equivalent have inspired me to issue a call for Accretionary Wedge #30: Let’s have a Bake Sale!

I hereby challenge my fellow geobloggers (and any newbies who want to participate) to explore the interconnections between geology and food. This can take any form you want, but I’m really hoping for some edible, geologically accurate models. Yummy stuff that illustrates and informs about earth science? Yes, it is possible!

Here’s an example from my own kitchen, several years ago:

A delicious analogy for the Blue Ridge Thrust Fault. I baked a chocolate & peanut butter cake last week. Yesterday, I baked a carrot cake. The carrot cake is younger; the chocolate cake is older. Then I shoved the older cake on top of the younger cake by pushing sideways (A). Traveling along a layer of icing, the older chocolate cake moved up and over the younger carrot cake. The surface of contact between the two is analogous to the Blue Ridge Thrust Fault, shown as a dotted line (B). Arrows show relative motions of the two cakes. This thrust-faulted cake was served at the NOVA-Annandale end-of-semester party for the Mathematics, Science and Engineering Department, May 2006. [From here]

What have you got, geobloggers? If it’s not baked goods specifically, I’m good with that. But something food related would be great. I’m lickerish for something delectably illustrative. Let your taste buds guide you on a geologic journey! Let’s plan on submitting our dishes to the Bake Sale by January 28, 2011, (by leaving a comment here including a link to your post) and I’ll lay out the smorgasbord over that weekend, so we can get this thing online by the last day of the month.

In the meantime, if you have a clever idea for the next Accretionary Wedge, or the one after that, leave a message in the lengthy chain of comments at “Who’s Hosting the Next Accretionary Wedge?” We’re a bit behind the game here with January’s announcement, but hopefully we can remedy that with enthusiastic participation in the planning of future Wedges. …Perhaps if everyone resolved to host a Wedge this year, and to submit suggestions a bit in advance? Thanks!

Mystery rock with radiating crystals

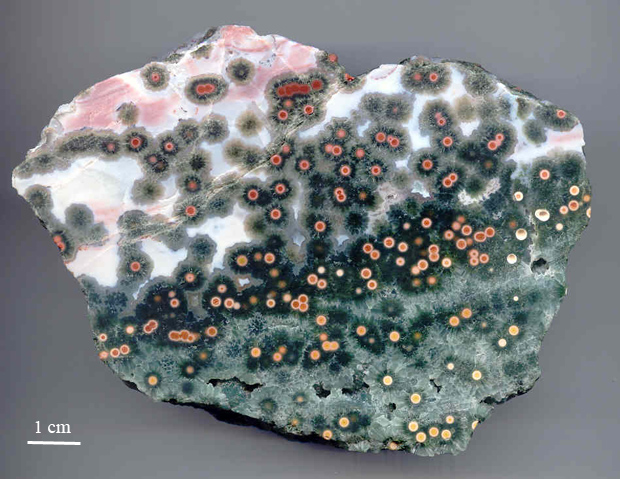

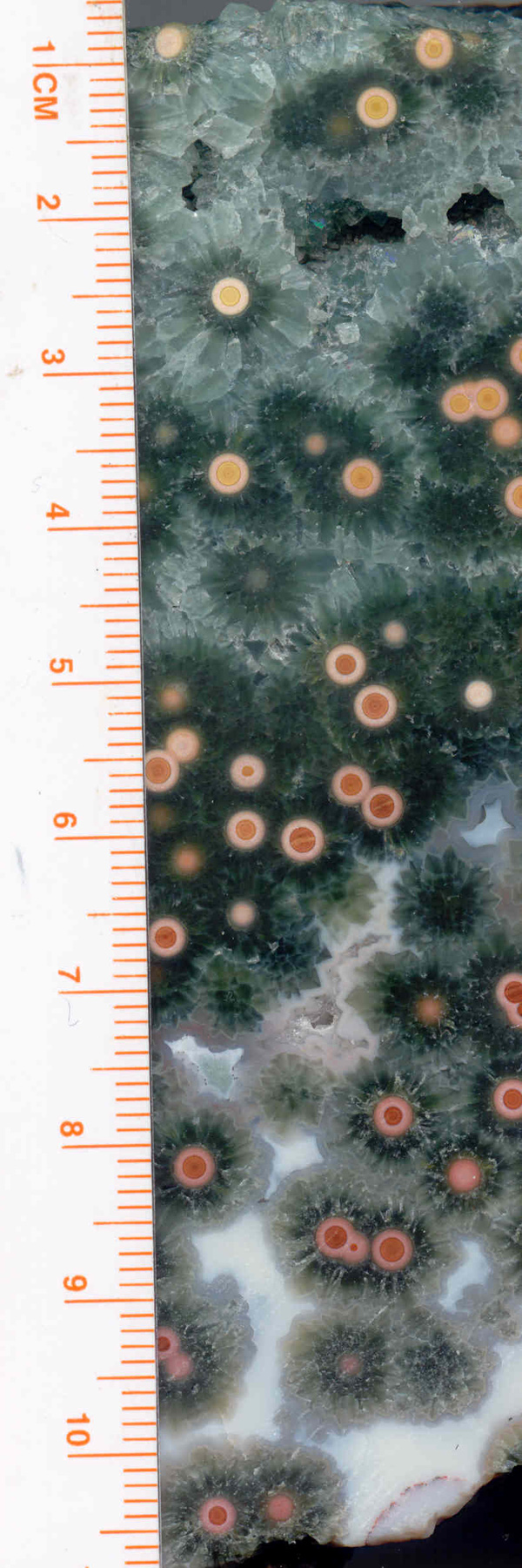

Putting up the wavellite crystals on Saturday reminded me that I needed to show you this thing and ask you to tell me what the hell it is:

I got this from an amateur geologist rockhound dude in Maryland, who got it from a collection of rocks hoarded up by another rockhound. When the one rockhound died, his widow let my rockhound go through the collection and claim whatever he wanted. My rockhound had this piece (bigger then) in his backyard, and then offered it to me. Because I have a rock saw, I suggested that I slice it in half, and we each keep a piece. So that’s what we did. Now here’s the question: what is this, and how did it form?

There’s no fizzing, anywhere. The little orbs are yellow on one side, and orange in the middle, and red on the other side, and everywhere they are surrounded with radiating green crystals that are stockier (non-acicular) than the wavellite in the previous post. These extend a distance, and then the space in between these mineralogical hedgehogs are either tightly clustered, with a gap in between them (as at the bottom), or they are more widely spaced (as at the top), with the intervening space filled with a white/red/pink cryptocrystalline matrix that looks and feels like chert.

What the heck? Tell me what to think of this oddball. Here’s a closer look, with a ruler for scale:

8 January 2011

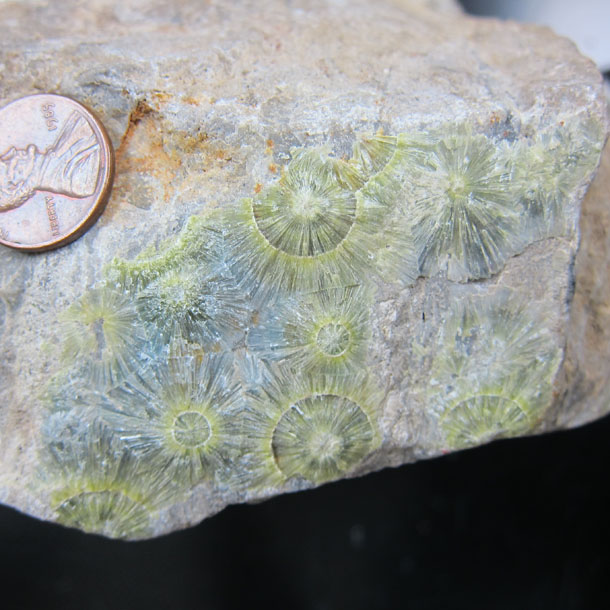

Radiating crystals of wavellite

My once and future Honors student Robin R. brought back some sweet wavellite [Al3(PO4)2(OH,F)3•5(H2O)] samples from her holiday travels*. Check out these beautiful radiating crystals! A penny will serve as your sense of scale.

The wavellite is a “crust” on top of a layered rock that appears to be a quartzite. (The layering in the quartzite is cross-cut by the wavellite layer.) It looks like the host rock fractured, then wavellite crystals grew in the fracture gap, radiating out from point nuclei, and meeting along fairly crisp edges. Ultimately, this team of wavellite crystals sealed the crack shut as a vein. When the rock was stressed again, it broke along the weak discontinuity between the wavellite vein and the host rock, baring their radial structure for all to see.

Seriously cool, right? Thanks to Robin for letting me photograph this pretty rock and post the images here. * She bought this from a rock shop in Amsterdam.

Seriously cool, right? Thanks to Robin for letting me photograph this pretty rock and post the images here. * She bought this from a rock shop in Amsterdam.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.