5 February 2011

Capadoccia 5

So where did we leave off with the Capadoccia photos? I think we mentioned a hike, right? Here’s Lily buying orange juice from two boys who operated a refreshment stand in the middle of nowhere.

There was a lot of good, fresh fruit in this dry land, a fact which surprised me. Here’s some apricots in a tree:

We emerged out of the valley in which we had been hiking and headed for the castle-like high point of Uçhisar:

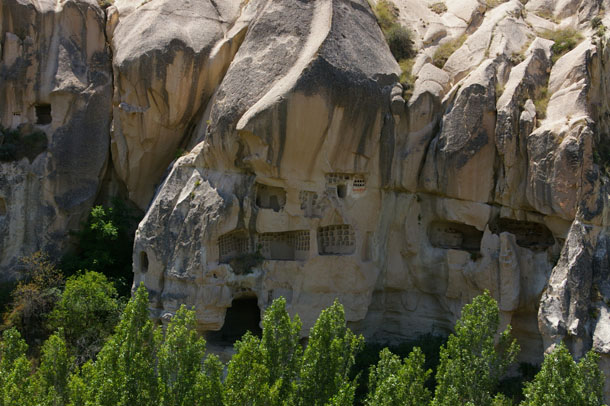

This proud knob of tuff has been thoroughly tunneled into, like a big ant hill.

On the way up to check it out, we saw some neat dwellings which conformed to the stratification of the tuff:

This one reminded me of a Hobbit hole:

A lot of the houses clustered on the flanks of Uçhisar had solar water heaters on their roofs. While they may be “primitive” in some regards, they also have this commonsense piece of modern technology:

Joints (highlighted by vegetation) cutting across pink tuff:

Climbing up higher, we could look down on a part of the Uçhisar town which had apparently been abandoned…

We stopped for coffee, and a bug crawled onto my leg:

Finally into the warren of buildings and streets surrounding the peak, we headed uphill and uphill. The tower of the mosque served as a landmark:

Here’s that same tower from a more elevated vantage point:

Gorgeous exposures of pink and yellow tuff in the ravine below the town, eh? A closer look:

Finally we got up to the formicary-like massif that dominates Uçhisar. It reminded me of the Flintstones:

View from the top, looking down a narrow defile:

The wall of this narrow valley, showing how intensely anthropologically modified it had become:

Inside, you could see soot stains from where generations of candles (or other lamps?) had been burned in small alcoves:

Climbing through this abandoned maze felt very Indiana Jones — archaeology and hidden dark tunnels. Where, for instance, do these stairs go?

Outside again, and in a position to appreciate our elevated vantage.

We stopped for some snacks, purchased from this fellow. Would we call him a nutmonger? Or a fruity nutmonger?

A study in contrasts is next: ancient eroded dove cotes…

… and adjacent tafoni (lens cap for scale):

We started to return to Göreme by way of the road, but that was nasty after all our time in the quiet valleys and the empty dwellings of Uçhisar “Castle,” so we detoured off the road and found a narrow little ravine that looked as if it would lead us to a bigger valley and back to Göreme:

This turned out to be kind of sketchy. We got to a point where we had to jump off a ledge and land in a pile of sediment ~7 feet below. It all worked out okay, but it was a little nerve-wracking. Soon the valley widened, and familiar “fairy towers” told us we were on the right track:

This one reminded me of Jabba the Hutt:

The trail generally followed the stream course (dry) and we had to occasionally scuttle through small tunnels that the stream had cut into the tuff, like this one.

It caught my eye because of the lovely stratification just above the tunnel “ceiling”:

A few more ancient, abandoned once-inhabited hoodoos…

… and we were back in Göreme proper. Can you tell where the town begins?

It’s all a matter of degree. In Capadoccia, nature fades into anthropogenic as gracefully as these towers taper into the sky.

4 February 2011

Friday fold: the importance of younging direction

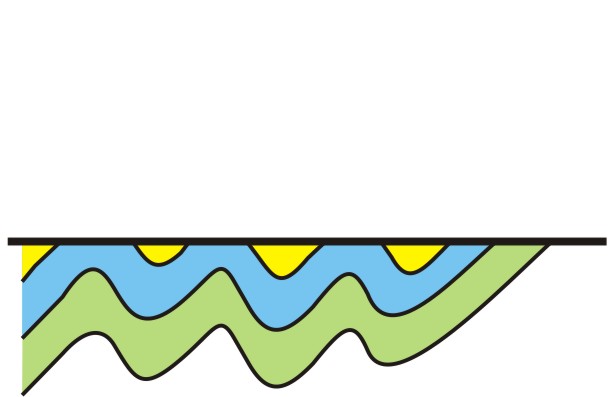

Today’s edition of the Friday fold is a cross-section:

Doesn’t look too spectacular, does it? — “Why, it’s just a bunch of strata folded into anticlines and synclines,” I’ll bet you’re thinking.

But no… it’s actually more complicated than that.

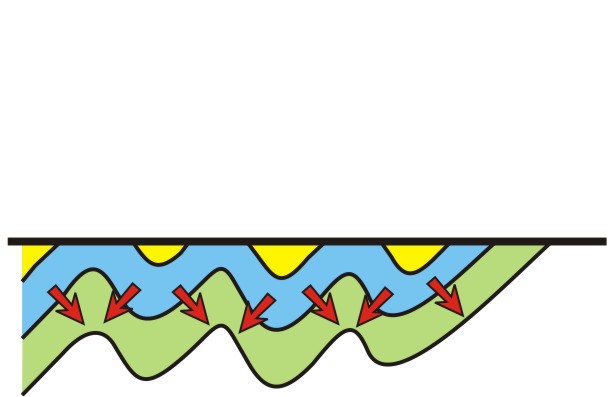

We know it’s more complicated by examining geopetal primary structures in the strata. Geopetal structures are primary structures which look different right-side-up than up-side-down. In sedimentary rocks, this includes things like graded bedding, ball & pillow, footprints, cross bedding, or mudcracks. In volcanic rocks, it might include the position of the entabulature in a basalt flow, or contact metamorphism along the bottom side of the flow, or the accumulation of vesicles towards the top of the flow. Say we find some of these “right-side-up” indicators in our blue layer, and it indicates the blue layer is “younging” towards the bottom. This implies the blue layer is up-side-down:

By paying attention to the “younging direction” of these strata, we have revealed a complication to their story. Rather than being “anticlines and synclines,” these must be antiforms and synforms. Any fold that goes up in the middle is an antiform, but only those with a stratigraphic sequence conforming to superposition (i.e., oldest on bottom & youngest on top) get to bear the name “anticline.” (Ditto for synclines — they’re only synforms until you demonstrate that the youngest is on top.)

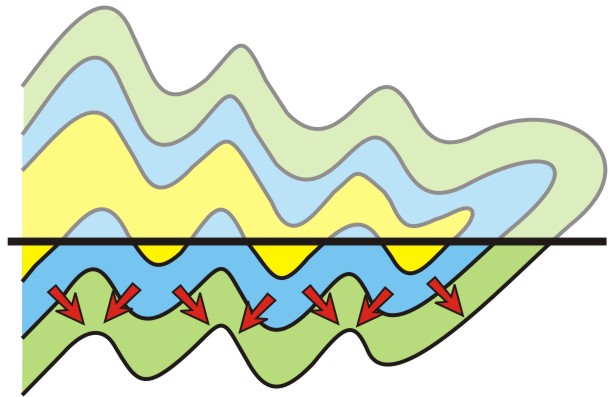

If these strata are up-side-down, then they have been overturned. One way to do that is by placing them on the tipped-over limb of a recumbent fold, like so:

The lightly-shaded upper part of the image is our interpretation of what the folded strata would have looked like prior to uplift and erosion, planing them down to the thick horizontal line that represents the trace of the ground surface. Notice that we’ve got two generations of folding here – an earlier isoclinal recumbent fold (very tight — limbs almost parallel, and with a horizontal axial plane) and a second generation which refolds the first (upright, almost symmetrical, vertical axial planes).

I drew these figures in CorelDraw for my Structural Geology class this week. On Wednesday, we talked about primary structures, including the geopetal ones, and I offer this as an example of why it’s important to note all kinds of non-tectonic structures when you’re doing field work — Otherwise, you might miss out on a tectonic structure like the big recumbent fold in this scenario.

Happy Friday to you.

2 February 2011

Capadoccia 4

On our second day in Capadoccia, Lily and I went for a walk through one of the valleys that are eroded into the landscape there.

Bas-relief hoodoos emerging from the wall of the canyon:

We came to one area with classic turret-like hoodoos:

Note the gravel layers in that column’s section, and the human at right for scale. The greater resistance to erosion of the upper (presumably ignimbritic ashflow) layer protects the more readily-eroded lower layers (ash fall?), and imparts the phallic shape to these hoodoos.

There was one photogenic area that had a bunch of these distinctive shapes in a cluster:

As we rounded a fin of eroded tuff, two things caught my eye. The first was this nice cross-section through a channel:

The tuff strata were eroded away, presumably by water but perhaps by some ignimbritic process, and the resulting scour was filled with gravel:

Hard to place a sense of scale in these photos. The deepest part of the channel is about 1 m deep. Rounding the fin to the sunlit side, here’s the outcrop of the channel:

A short distance away was a nice normal fault. Here’s a photo on the shady side of the tuff fin, with a lens cap for scale:

And on the other side of the fin, here it is in the sun:

A bit further up the valley, we saw Capadoccia’s answer to Half Dome:

Undercutting and oversteepening by the local stream no doubt undermined this particular “fairy tower,” causing it to partially collapse.

Here’s a similar situation, a block which has slid off the face of the canyon wall (now has trees growing on it in the foreground):

The little “doors” you see on the scarp face are tombs. These are readily distinguished because usually they are high above the valley floor (more inaccessible to looters), walled off, and equipped with a series of small air holes at the top.

1 February 2011

Capadoccia 3

Today is the umpteenth nasty cold bleak winter day in a row here in Washington, DC, and it’s really nice for me to be able to dip into my reserve of photos from warmer times this past June in Turkey. Here’s some more Capadoccia photos for you to enjoy:

Check out the dove cotes in the next two:

The previous image shows some of the layering that can be observed in the tuff. As the pyroclastic flows tumbled over this area, they lay down massive, internally-poorly-stratified layers. During calmer intervals, ash falls deposited more discernible strata on the scorched ground. These same layers can be traced out inside the dwellings that the Capadoccians carved into the tuff:

See the layer in that last photo, right in the middle of the wall?

Here’s another look at the texture of the tuff in a more poorly-sorted section (lens cap for scale):

In some places, Byzantine inhabitants of these Flintstone-esque shelters decorated them with Christian iconography:

These charming images are in many places defaced or destroyed, thanks to the subsequent spread of Islam and its “no icons” rule.

Exploring the interior of the “fairy towers” is a lot of fun — a big three-dimensional maze of history and archaeology and geology…

Lily poses next to a table and benches carved into the floor and wall — part of the architectural plan:

More decorations (ochre colored) on the interior walls and ceiling of a damaged dwelling:

Distinctively shaped alcoves in the above image, which are mirrored in the distinctively shaped door, seen below:

One more, just for fun — an Indiana Jones moment — fleeing the rolling boulder:

Made it out — just in the nick of time!

31 January 2011

Accretionary Wedge #30: the Bake Sale

I hope you’re hungry, for the 30th edition of the Accretionary Wedge geo-blog carnival is all about food. It’s the Bake Sale! Let’s start our feast with something substantial, and only then move on to the dessert smorgasbord.

Andrew Alden, geology guide at About.com, has all kinds of ideas on the relationship between geology and food. If you’re not sure if you’ve got a potato or a meteorite, then check out some of his geologic recipes for kids on this page.

Perhaps some meatloaf would make a proper main course. Ron Schott thought so, and on Ron Schott’s Geology Home Companion blog, he baked a meatloaf in the shape of a roche moutonée, those glacially-sculpted bumps of bedrock. I love how the bacon strips mimic the glacial striae; Only thing could make this meatloaf better… and that’s if the “meat” were mutton, to better match its geomorphic model’s namesake. Here, I’ve annotated one of Ron’s photos to show the glacial ice with the flow direction moving over this chunk of savory goodness:

Accompanying the meatloaf should be something starchy. Matt Kuchta showcases the mechanical properties of (uncooked) pasta in a post on his blog Research at a Snail’s Pace. There, in images and video, he shows us about elastic rebound theory, but the final frames of the video (wherein he eats uncooked pasta) don’t make it look all that appetizing.

Another possibility is bread. Here, in German (but with lots of pretty pictures) is a post from Lutz Geissler that basically argues that bread loaves mimic the shape of lava pillows. (Lutz usually blogs at Geoberg.de, for those who don’t know.)

Kathy Cashman and Alison Rust were thinking along similar lines when they penned a guest post for Earth Science Erratics on vesicles, lava bombs, and sourdough bread.

Anne Jefferson of Highly Allochthonous brought the final healthy dish to our potluck. She made a veggie pilaf with broccoli, onion, rice, lentil, potato, portabella, garlic, pepper, salt, coriander, ginger, and barley. Then she set it up on an oversteepened slope, and let ‘er rip. The result was a miniature debris flow that showed some patterns that mimicked natural mass wasting events.

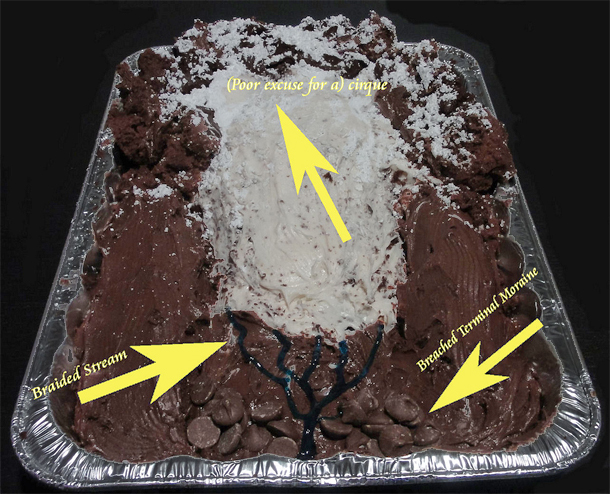

Dana Hunter (who writes En Tequila Es Verdad) also focused on surface processes with her contribution. She baked a glaciated cake to depict the geomorphic processes which yielded her neighboring Cascade Mountains.

Jim Lehane brings out our second dessert course with a neat comparison in the shake-ability of Rice Krispie treats versus Jello: Which dessert is better to build the foundation of your house on? Follow the recipe for disaster (“dessertaster?”) at The Geology P.A.G.E.

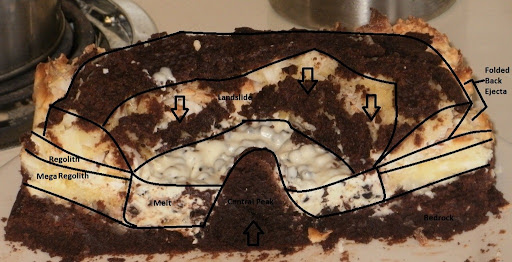

Helena Heliotrope, who writes the blog Liberty, Equality, and Geology, contributed a baked model of the lunar surface, complete with coconut regolith and a basalt-tapping, meteorite impact and the breccia that filled its crater.

Anne Jefferson also pointed out that Maria Brumm from the now (sadly) inactive Green Gabbro had somewhat addressed this “sweet stuff shows geology” theme back in 2008:

Igneous petrology of ice cream (and an example that makes “xenoliths”)

Metamorphic petrology of ice cream

Sedimentary geology of ice cream

Lockwood of Outside the Interzone also dug into the archives with this post from last June, combining a series of fantasy cake images (for Nissan cars, of all things) with some actual photos of a “zebra” cake with gneissic banding. Lockwood was also kind enough to point to the Friends of the Pleistocene geo-art blog, which explored some of the connections between food and geology in a recent post called “Food for Thinkers”.

Lockwood was Mr. Link-tastic with this edition of the Wedge, pointing to all sorts of relevant posts, but he also delved into a really neat experiment on how to convert your own breath into calcite, an exercise which prompts reflections on the cycling of carbon through biological and geological reservoirs. Go check it out (bonus: you get to see what calcium looks like in its elemental state!)

Jessica Ball of Magma Cum Laude decided that she wanted to bake something relevant to her own volcanologic research, and so she made up a batch of rheomorphic tuff. As with the real-life inspiration, her cake has layers of mafic and felsic minerals that make a very impressive outcrop pattern:

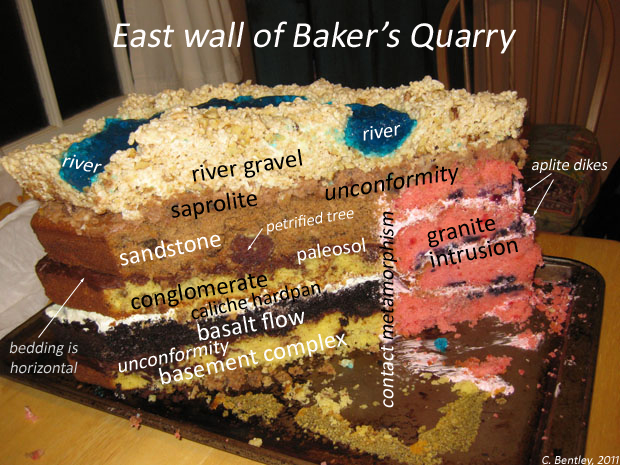

An illustrated hypotheti-cake inspired me to bake something real that illustrated geologic principles. It led me to create a concoction that I dubbed “Baker’s Quarry,” and I explored its fake geology, and the story behind the real cake in a couple of posts.

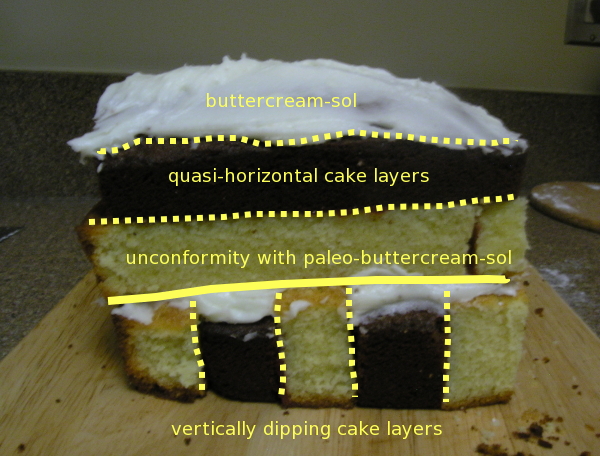

For Chris Rowan of Highly Allochthonous, it was also all about the cross-section and the story it implied. Taking on the most famous unconformity outcrop in the world, the Siccar Point outcrop discovered by James Hutton, Chris baked a cake to match, and explained how it came to be that way.

Garry Hayes, a.k.a. Geotripper, brought forth a double-header – he started off with a block diagram of subduction rendered in icing, and then finished it off with a tray full of trilobite cookies.

If you like eating trilobite cookies, then other paleontologically-themed confections might appeal, like this Aardonyx cake from Adam Yates of the blog Dracovenator.

(Thanks to David Orr (@anatotitan) for alerting me to this via Twitter.)

There’s even a dinosaur “extinction hypotheses” cake, which is featured in this YouTube video:

Cian Dawson of Point Source also baked a cake that featured dinosaurs on top, but those beasts were but surface phenomena. Cian was interested in going down beneath them to examine the hydrology below the surface. His post on a “hydrogeologically correct cake” gives all the details.

Ann of Ann’s Musings on Geology and Other Things has a cake which reminded me of paleotology: it’s got a fossil baby in it! Called “King Cakes,” these macabre pastries are apparently a New Orleans tradition. Mmm, after all these fine desserts, I was feeling a bit stuffed, but if there’s one thing that could motivate me to dive into yet another cake, it’s the prospect of finding a plastic child inside it:

Curiously, the “King cake” tradition is motivated not by physical anthropology, but by religion. Check out Ann’s post to learn more.

To wash down all this cake, you might appreciate a cup of coffee. How about a cup of coffee that’s been sitting on the counter for two weeks? Silver Fox finds one in just that situation, and she deduced its age from counting the strandlines it left on the inside of her mug! Check it out at Looking for Detachment – very cool application of geological thinking to an everyday phenomenon.

And one more: Elli of Life In Plane Light suggests baked a cake with the intention to make a “schist” analogue, but it actually works better as an analogy for crystal settling. Check it out: all the chocolate chips sunk to the bottom of the batter “magma chamber” —

Check it out at her blog. While you’re at it, check out her use of corn syrup as an analogue for lava viscosity.

Thanks to everyone for their delectable contributions. Depending on how you count (intentional baking projects vs. links that just fit the theme) we had something like 21 individuals contributing to the 30th edition of the Accretionary Wedge.

29 January 2011

Capadoccia 2b – panorama

Click this image to go to a big panorama (but not big enough to be hosted by Gigapan) of one of the valleys near Göreme, Capadoccia, Turkey:

Note:

The agriculture that lines the bottom of the valley.

The colors of the tuff, and how they vary from place to place.

The differentially eroding layer that dips off to the left (best exposed on the right).

28 January 2011

Friday fold: Mavericks

On Monday, a post at Geology in Motion about an injured surfer alerted me to a beautiful bathymetric expression of today’s folds offshore of California’s primo surfing locale, a break called Mavericks.

According to the source website, the sinuous ridges we see in the offshore bathymetry are Pliocene sedimentary strata. Movement along the San Gregorio Fault folded and uplifted these strata. Apparently, this submarine configuration is instrumental in producing the notoriously big waves at Mavericks.

You can also see these folds in Google Maps, though that application’s hokey shoreline “wave effect” obscures the best expression of the contorted strata.

27 January 2011

Do the math

A video, “The Dreaded Stairs,” has been getting some circulation lately on Facebook. It shows what happens when a staircase (beside an escalator) gets a makeover which features piano-style keys which make sounds when they are trod upon. Watch the video if you would like; I’m going to focus on the accompanying blurb, which reads:

There is a set of stairs, with a moving escalator next to it …. both of which lead to the same spot on the floor of the upper level. At first no one took the stairs, almost 97% of the people took the escalator. Okay. I think that could be a normal expected result.

Then a group of engineers got together, and decided they wanted to change the percentage around.

Notice what these scientists did. Clever huh. And now they have reversed the percentages, as a whopping 66% more people take the stairs, than ride the escalator.

Now that sounds pretty impressive at first glance — this clever (and I’m sure expensive) treatment resulted in the before/after numbers going from ‘97% escalator’ to ‘66% stairs.’ But wait a second… are those two numbers actually comparable? Is that really what’s being presented? Or only what’s being implied?

If 97% of pre-piano-treatment people took the escalator, that means:

100% – 97% = 3%

3% didn’t take the escalator (and presumably took the stairs instead).

The second number is not ‘66% of people took the stairs’ post-treatment. That would be direct and unambiguous, and wouldn’t have inspired me to chew into this with a blog post. Instead, it says that “66% more.” The key word here is “more,” and how we choose to interpret it. One possibility is that “more” refers to the pre-treatment state of affairs. This was the first meaning of “more” to jump to my mind — a comparison of post-piano-treatment to pre-treatment. If this interpretation is the correct one, it means ‘66% more than the original 3%.’

3% x 1.66 = 4.98%

If this interpretation of the “more” in “a whopping 66% more” is correct, then the video blurb is intentionally misleading. Going from 3% to 4.98% is not particularly noteworthy, especially if no accompanying statistical treatment shows that it is in fact a significant increase from the pre-treatment state. A variation of less than 2% may well be statistically significant, but no evidence is provided for that assertion.

A second, more charitable interpretation of “66% more” might be that the post-treatment situation has a new status quo wherein x% of people take the escalator, and y% of people take the stairs. In other words, “more” might refer to the present ‘stairs’ versus ‘escalator,’ and not to ‘before’ versus ‘after.’

So let’s try that interpretation out instead. According to the blurb, if x is the percentage of escalator people and y is the percentage of stairs people,

y = x + 0.66x

y = 1.66x

Because the stairs and the escalator are the only two options,

x + y = 100%

Therefore,

x + 1.66x = 100%

2.66x = 100%

(2.66x)/2.66 = (100%)/2.66

x = 37.59%

And, since y = 1.66x, then y = 62.39%

So, if this second interpretation of “more” is the one intended by the authors of the video blurb, then the actual increase in stairs usage is from 3% before the piano treatment to 62.39% after the piano treatment.

62.39% / 3% = 20.8

If the second interpretation of “more” is correct, the treatment resulted in almost 21 times the pre-treatment number of people who take the stairs! It represents 2100% of the original number! Another way of saying that is an increase of 2000% beyond the original. That’s a great number regardless of the particulars of how it is expressed, and worth crowing about. One wonders why the written blurb accompanying the video doesn’t tout this number instead of the relatively weak phrase “a whopping 60% more.”

The fact the the blurb authors opted for “60% more” instead of “21 times more” leaves me inclined to think that my first interpretation of the word “more” was correct. Which means of course, that compared to the alternative, “more” means less (than it is implied to mean).

A bit of selective video editing, and a mathematically unreflective population of video viewers, and you’re left with the public perception of an apparent masterwork of engineering achievement. Soon all our stairs will be coated with piano keys …and perhaps 2% more of us will take them.

Cappadocia 1

Today, you get the first of several batches of photos dealing with one of the most magical places I’ve ever been, the Cappadocia region of Turkey.

Cappadocia (pronounced “kap-uh-doke-ee-yuh“) is an area of eroded volcanic tuffs. The overall effect is badlands-like, but without the micro-turrets and hoodoos. The individual erosional remnants are larger in Cappadocia than in places like Bryce Canyon, Utah. Why this is, I don’t know – it could be a difference in climate, or perhaps the nature of the rock being eroded. Bryce is lake sediments; Cappadocia is semi-lithified volcanic tuff. Whether I’d go so far as to dub it “welded” is another question — it’s certainly far more friable and carvable than the “Ig2” layer in the Bishop Tuff.

Here’s a shot to show an exposure with typical texture:

That’s a lens cap for scale at right. Note the large chunks of pumice, and the large variety of sizes of lithic inclusions. The volcano responsible for belching out most of the Cappadocian tuffs is nearby Erciyes Dağı.

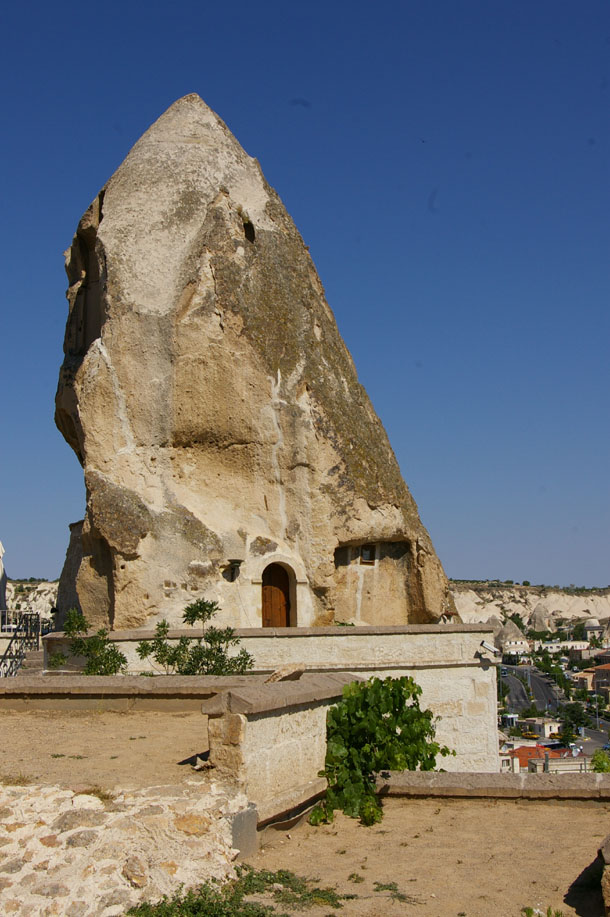

But no one travels to Cappadocia for its pumice inclusions. They go for the weathering pattern, and this is what that looks like:

The whole landscape is covered in big pinnacles like this, mega-hoodoos that people have been living inside for millennia. The humans have carved out cave-like dwellings with horizontal floors and ceilings, and vertical walls, and sometimes adorned them with carvings of moderate complexity, like these two “Roman” (not really) pillars seen downtown in the village of Göreme:

(I’m toasting them with a glass of Efes pilsner, which is what you drink in Turkey.)

Where the hoodoos alone were insufficient, the Cappadocians cut out blocks of the ignimbrite and added on, constructing dwellings in a more traditional fashion.

The combination of building styles is what characterizes this region and makes it so charming — it is at once natural and anthropogenic:

Here is an overview of part of Göreme:

To explore Göreme on your own, check out this gigapan:

Here’s a couple of Cappadocian abodes which have cracked open, revealing the warren inside like a dissected anthill:

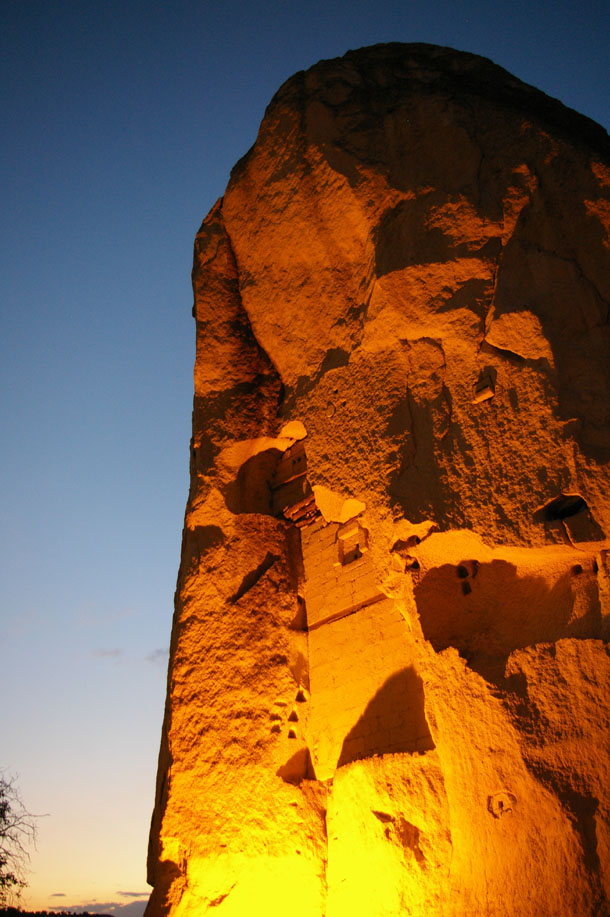

A few night shots of this amazing place, to round out the post:

This last one was the hotel that we stayed at. Our room was carved right into the tuff! Here’s a view of this rustic luxury:

More Cappadocia images to come — we spent several days here, exploring the countryside.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.