14 June 2015

Art in Science: Kubiena’s Soil Profiles in Watercolors

Posted by John Freeland

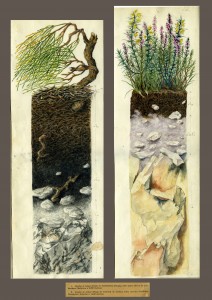

Watercolor #10 (organic soil over gneiss) (L) and podzolic soil over quartzite (R)) by Walter.L Kubiena ( Instituto de Ciensias Agrarias), click for larger image.

Photographs of soil profiles are often disappointing. Usually the subject is a hole in the ground where light is dim and the surrounding ground surface is light. Getting a good, representative photo of a soil profile can lead to acres of frustration.

W.L. Kubiena worked as a soil morphologist in the last century and from a practical standpoint, probably only had access to black and white photography. He opted for watercolors to describe the often rich colors of soil profiles. Looking at his paintings for the first time, recently, and not having the artistic literacy to describe them in a meaningful way, I was struck by the passion he must have felt for his subject – the soil.

Kubiena completed The Atlas of Soil Profiles, basically a collection of plates, in 1954. Prior to that the watercolors accompanied a more technical text in Kubiena’s Soils of Europe (available through book sellers). There were requests to make the paintings available in a separate format whereby pages could be separated, framed and hung on a wall. For Kubiena, prehaps reluctantly, there was a place for coffee table books in the compendium of soil science literature. From the Atlas

There are amateurs who profit more from the contemplation of loose plates in a portfolio than from searching them from the pages of a book.

Kubiena’s name is on the book but the painting was actually done by Gertrude Kallab Purtscher and Anton Prazak. Kubiena apparently interpreted the profile morphology, sketching and demarcating horizons, and collaborated with the two illustrators on the color renderings.

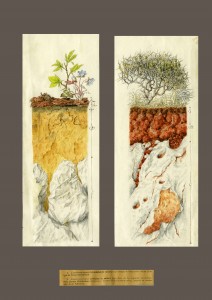

Here are two more examples from Kubiena’s Atlas:

Watercolor #22 by Walter L. Kubiena (both Podzols with bleached E horizons underlain by Bhs horizons rich in illuviated humus and iron)

Paint vs. Photography

Why should scientists use brushes and paint to illustrate natural phenomena? Wouldn’t a photograph be more realistic? It has to do with “artistic license.” Freedom to choose colors, brightness, and hue from a paint pallet empowers the scientist to emphasize morphological features and connect form to concepts and processes.

For example, in Watercolorr #22, both profiles show a whitish eluviated (E) horizon sandwiched between the organic-rich topsoil (A) horizon and the underlying (B) horizon where materials stripped from the E horizon by water infiltration accumulate. The stark visual contrast between horizons suggests (correctly) something very different is occurring at different depths of the soil profile.

Art in Other Science Disciplines

The “Peterson Method”

The Peterson Field Guides (birds and more) are a good example of “practical biological art” and are

“based on patternistic drawings with arrows that pinpoint key field marks…a pictorial key based on readily noticed visual impressions rather than technical features.”

Peterson has taken this approach beyond birding to describe animals and natural phenomena.

Medical Illustration

The Association of Medical Illustrators is all about “illuminating the science of life.” Johns-Hopkins graduate school offers a program in medical and biological illustration and a gallery of faculty and student work is found here.

An Eye for Composition

I remember my graduate advisor Jimmie Richardson making the off-the-cuff remark “I need to look at the earth every day.” For him, that was undoubtedly one reason for running the country roads around Fargo, training for marathons, and hiking mountains of Idaho. I “got” that, what he said. I feel that way, too.

While quantification is a huge aspect of science, I suspect more geoscientists are drawn to their subject by the way the colors of the landscape change as the sun moves slowly across the sky than by a passion for Stokes Law, the Universal Soil Loss Equation, or some other formula.

Professors and field instructors, here’s a suggested activity. Take your students to an outcrop or other area of interest. Have them shut off their smart phones and put them away (they probably won’t have reception anyway). They can use paper and a set of colored pencils to illustrate what they see. Watch for the student who stays longest on task getting every detail, every nuance, straining to get it right until “smoke pours out their ears.” You might find a new “star.”

John Freeland earned a PhD in Soil Science (Pedology) at North Dakota State University and is a consultant working in the private sector. He has published soils research and taught at the high school and college levels. John is interested in wetlands, soil genesis, science communication, the intersection of art and science, and soil-water-landscape processes. John lives near the Ohio-Michigan border and plays bass in multiple music projects.

John Freeland earned a PhD in Soil Science (Pedology) at North Dakota State University and is a consultant working in the private sector. He has published soils research and taught at the high school and college levels. John is interested in wetlands, soil genesis, science communication, the intersection of art and science, and soil-water-landscape processes. John lives near the Ohio-Michigan border and plays bass in multiple music projects.

[…] Photographs of soil profiles are often disappointing. Usually the subject is a hole in the ground where light is dim and the surrounding ground surface is light. Getting a good, representative photo of a soil profile can lead to acres of frustration.W.L. Kubiena worked as a soil morphologist in the last century and from a practical standpoint, probably only had access to black and white photography. He opted for watercolors to describe the often rich colors of soil profiles. Looking at his paintings for the first time, recently, and not having the artistic literacy to describe them in a meaningful way, I was struck by the passion he must have felt for his subject – the soil.Kubiena completed The Atlas of Soil Profiles, basically a collection of plates, in 1954. Prior to that the watercolors accompanied a more technical text in Kubiena’s Soils of Europe (available through book sellers). […]

Dear John Freeland,

Thank you for showing these beautiful watercolors done by Walter Kubiena, Gertrude Kallab Purtscher and Anton Prazak. I alo appreciated the definition of soil that figures under the page title Terra Central, “the intersection of lithosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and society”. “and society” is unusual in a soil definition, but very true and important. The best for you and soil, cordially, Augusto (a humus lover).

Augusto:

Thank you for the kind words. I’m glad you apprecated the watercolors, which uniquely and so beautifully illustrate the concepts Kubiena sought to convey. I’m surprised that I completed an MS and PhD in Soil Science without ever having seen them. Thankfully, they seem well preserved.

All the best,

John