30 March 2011

Thinking (of science) like a journalist: A physicist’s take on a media training workshop

Guest post by Mary Z. Fuka, physicist and founder, TriplePoint Physics, LLC in Boulder, Colorado.

Clear and accessible science communication has been a priority throughout my 20-year scientific career as a physicist working in wildly interdisciplinary entrepreneurial R&D settings. Like most scientists, I’ve not had much occasion to talk to “the media,” but I’m also a science news junkie and aware that the thirst for information among the public is increasing. Then, too, I spend a lot of time talking about my work to folks from other backgrounds; whether informally as a friend and neighbor or as part of scientific outreach efforts like the American Physical Society’s high-school-level “Adopt-A-Physicist” program. So I feel a need, even an obligation, to talk effectively about science in my day-to-day work and personal life, and I perpetually seek opportunities to improve my communication skills.

I was therefore delighted to participate last week in one of AGU’s science communication workshops at the Chapman Conference on Climates, Past Landscapes and Civilizations in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The conference promised an exciting week of interdisciplinary archaeological, geoscience and climatology research focused on understanding humanity as a geophysical force during the Holocene Epoch. One overarching conference theme was communication among scientists from disparate backgrounds, another, communicating what we’re learning about human-influenced geophysical change to the wider public audience. Expanding my science communication horizons in the workshop was the perfect complement to these themes.

The workshop featured three two-hour sessions over the course of the week. The first was on working with journalists; the second, on engaging online via social media; and the third was a practicum on how to craft one’s message when talking science.

I was particularly interested in the first. “After all,” I thought, “I seem to recall gene- sequencing studies from several years ago that show the human and chimpanzee genome are 96% the same. I bet that scientists, journalists and humans have even more in common. Perhaps learning how to talk with journalists will apply to communicating with the rest of humanity.” Like I said—I’m always eager to improve my communication skills.

I was not disappointed.

The dozen or so participants were a varied group of archaeologists, geoscientists and combinations thereof, along with a surprise outlier from international finance. Direct experience with the news media varied from none to some. For those with some experience, the encounters had sometimes been unsatisfactory. Reasons for attending were representative of why any of us as scientists might want to sign up for this type of training: general curiosity, interest in increasing research profile in the public eye, and learning how to interview more effectively, among many others.

We began with the basics of the science news cycle as embodied in the famous PhDComics vignette, “The Science News Cycle”. Then, a discussion of what makes science news, followed by a detailed description of the interview process from first contact to post-publication follow-up. Another participant commented to me afterwards that she felt the background coverage was “just right”—enough to fill us in on a new area without belaboring the points or talking down to the audience.

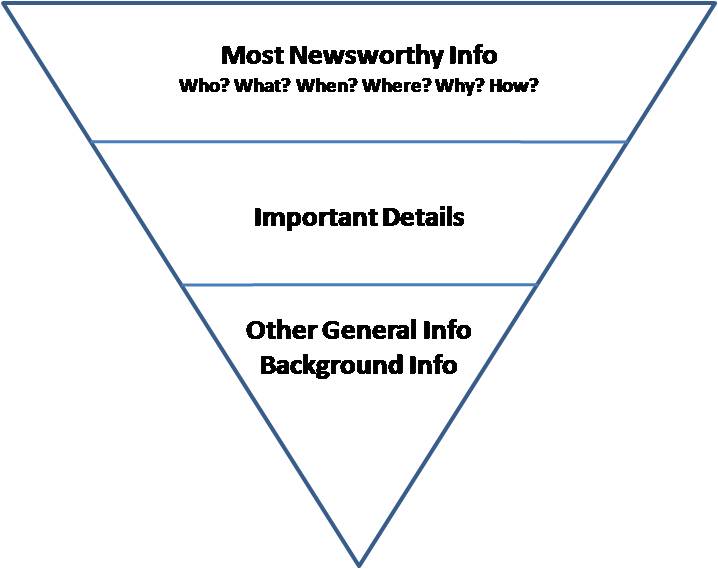

Among the many topics discussed, two themes especially stick with me. The first was conveyed in a powerful image of a news story as an upside down pyramid that stands formal scientific communication on its pointy head: Start with the exciting conclusion. Leave the gory details for later. In future, when eyes glaze over in conversations, I’ll imagine that pyramid point drilling down into my head as a corrective against inappropriate lapses into formal communication style.

The second theme that really grabbed me was the importance of regarding science communication as a two-way street. To inform the public, we need to get our stories out to the media rather than simply hope they’ll somehow find us. The workshop was truly illuminating on just how many ways there are to do that. The availability of public information resources in our professional organizations was an eye-opener for me—for example, I had no idea of the active role AGU takes in promoting the work of its regular members presented at AGU meetings or published in its journals. Communicating science—it’s not just for the IPCC. It’s for everyone.

[scribd id=51907615 key=key-ip398h7kcck3pqqu5g3 mode=slideshow]

The workshop culminated with an unexpected and timely case study: AGU had released a story on the Everglades tree-island research that workshop attendee Gail Chmura was presenting at the conference. Several major science news outlets had picked up the story. In fact, Gail had spent the afternoon giving interviews to journalists. She was able to catch us at the tail end of the workshop with her up-close-and-personal account of dealing in practice with what we’d spent two hours discussing as theory.

We pounced on her, of course, questioning her rapid-fire. Her comments on what she’d experienced were fascinating, amusing, a bit scary, but largely reassuring. Scary, in that the pitfalls she encountered could’ve been scripted from the workshop topics—tough questions, emphasis on exciting story over research nuances, and differences in communication style and language. Reassuring because in the final analysis, she’d emerged triumphant! Her story was told. The journalists even seemed to have “gotten it.” Above all, she seemed ultimately to not only have survived, but even enjoyed her Close Encounter of the Fourth Estate Kind. Her tale was a wonderful finish to a thought-provoking afternoon.

In sum: If you get the chance to attend an AGU (or any other) workshop on communicating science, do it.You won’t regret it. I came away with a certain skew to my view that informed the entire week of conferencing. Let’s call this usefully warped perspective “thinking like a journalist.” Or, perhaps, “thinking like a journalist’s audience.” Or even “thinking like our fellow humans, the people who we’d like to understand and benefit from our work as scientists.”

Which is perhaps how we as scientists should think more often.

— Mary Z. Fuka, physicist and founder, TriplePoint Physics, LLC in Boulder, Colorado.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.