30 December 2019

Wildfire modeling helps predict fires in Colombia

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

Early warning systems direct resources and benefit human health

By Amanda Heidt

A new wildfire model helps predict where and when wildfires will start in the Aburrá Valley of Colombia. This research, presented earlier this month at the 2019 American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco, is helping local cities avoid the devastating environmental and health impacts of fires.

The Aburrá Valley has been particularly susceptible to dry conditions brought on by El Niño in the last decade, according to researchers.

Fire departments in Colombia are now using the new model to identify and monitor sensitive areas throughout the dry season and direct resources as fires break out. Citizen scientists are also using the model’s results as part of a project to monitor air quality throughout the valley.

“We are really the early warning system,” said Nicolas Velásquez, a postdoctoral student at the University of Iowa who assisted on the project while at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

In Colombia, many local fire departments are staffed by volunteers operating independently with little communication between groups. The model helps unify efforts to stop fires before they start by providing consistent information. As the model identifies new regions of high risk, response teams can move to clear potentially dangerous clutter such as trash or illegal bonfires.

The new model serves as an anchor point for prompt action, according to researchers. Paulo Artaxo, an atmospheric physicist at the University of São Paulo who was not involved in the study, thinks robust models will be central to improving forecasting in wildfire detection.

“If you want to decrease the vulnerability of society to fires, this is exactly what has to be done,” Artaxo said. “On a smaller scale, you can control the parameters more easily, but doing this kind of research for the overall Amazonia will be extremely important.”

Predicting where fires will break out

The new model generates hourly reports of areas where wildfires are likely to break out, using data such as land cover, soil moisture, rainfall and temperature. Variables like land cover remain fairly static over time, but factors like rainfall and temperature change from day to day. Researchers are using the model to send up-to-date information to fire departments throughout the region. When updated data is published, it gets rolled into the model, keeping it precise and predictive over time.

“We have groups working on each variable to map them across the valley,” said Sebastián Ospina, an undergraduate on the project who presented the results at Fall Meeting. Ospina works for SIATA, a team of regional professionals that helped populate the model.

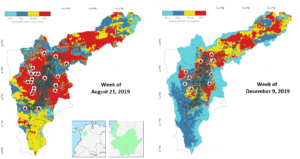

A side-by-side comparison of the model’s predicted fire likelihood in the dry (left) and wet (right) season.

Credit: SIATA.

Results show that regions surrounding larger cities are often listed as having “high” likelihoods for wildfire during the dry season. In the Aburrá Valley, fires are often the result of intentional land clearing as urban centers encroach into nearby wilderness. Every dry season, Velásquez said, they see fires popping up along the edges of cities.

In addition, moisture and rainfall in particular were found to be strong influencers of fire risk. Areas which receive higher rainfall or more consecutive days of rain are unsurprisingly less prone to fires.

Citizen scientists help out

The team developed small and inexpensive air quality monitors that were distributed to 250 citizen scientists throughout the valley.

Credit: Daniela García (SIATA).

This model first came into use in 2017 and has proven useful in directing resources to areas of highest concern. Now, the team is looking for ways to use their findings for tangible social benefits. Fires are an obvious detriment to the environment, but they also impact the health of residents.

“The model was just one part,” Velásquez said. “After the development [of the model] we wanted to look at the whole picture to monitor fires in real time and track air quality.”

SIATA assisted in the development of a small, inexpensive air quality monitor and distributed it to 250 citizen scientists. Mounted on buildings and pedaled around cities on bikes, the readings provide a dynamic, real-time assessment of air quality throughout the region.

During a recent fire in 2017, the researchers used the censor data to document a spike in particulate material that is fine enough to damage the lungs. The same sensors tracked wind direction, showing where the particles were most likely to build up in urban centers.

In addition, they are now deploying a series of cameras throughout the most high-risk areas to monitor for new fires. Using drones, they can provide information on flame and smoke column conditions and map the areas to asses changes in ground cover before and after a fire.

As unprecedented wildfires grip neighboring Brazil, researchers say more attention is being paid to long-term monitoring. This model, although only two years old, will provide valuable baseline knowledge moving forward into an uncertain future under climate change predictions.

— Amanda Heidt is a current student in the UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program. You can follow her on Twitter at @Scatter_Cushion.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.