2 January 2020

Research sheds light on the Moon’s dark craters

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

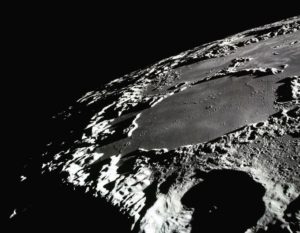

New research provides insights into chemicals trapped in the Moon’s dark craters and the conditions necessary for them to collect there.

Credit: NASA.

By Zain Humayun

The next wave of robots to fly to Mars in 2020 could offer scientists an unprecedented understanding of Earth’s closest neighboring planet. But there are still mysteries to be solved much closer to home, on Earth’s own Moon.

Last month at AGU’s Fall Meeting in San Francisco, planetary scientists presented new insights into chemicals trapped in the Moon’s dark craters and the conditions necessary for them to collect there. The research could help scientists understand whether these chemicals could be a potential resource for future missions to the Moon, according to the researchers.

The Earth tilts about its axis as it moves around the Sun. This means that any given moment, one of Earth’s poles is closer to the Sun than the other (this explains why Americans head to the beach, while Australians layer up). But Earth’s Moon doesn’t tilt like this. Instead, there are craters near the Moon’s poles that never receive any sunlight. Permanently engulfed in frigid darkness, these craters are appropriately called cold traps.

The Moon’s craters are scars from the comets that have been crashing into it for billions of years. These comets are made of compounds like water vapor, carbon dioxide, and methane. Without the protection of an Earth-like atmosphere, most of these chemicals break down in sunlight and escape into space. But if these chemicals – known as volatiles, for their low boiling points – end up in the Moon’s cold traps, they can stay frozen for billions of years.

“Understanding the inventory of volatiles and these cold traps is really good for being a potential resource,” said Dana Hurley, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University who presented the work. If humans ever set up settlements on the Moon, they could use water for consumption and methane for fuel. In a new study, Hurley and her colleagues researched the conditions necessary for volatiles to collect in the moon’s cold traps.

Some craters near the Moon’s poles never receive any sunlight. Permanently engulfed in frigid darkness, these craters are appropriately called cold traps.

Credit: NASA.

Identifying volatiles in cold traps is challenging because they are shrouded in darkness. For over a decade, NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, or LRO, has been measuring the faint UV light that emanates from stars and hydrogen in space and reflects off the moon’s cold traps. In 2019, scientists examined the reflection data from a crater named Faustini. They found an abrupt change in reflection that corresponded to ice, but also one that they thought could indicate the presence of carbon dioxide.

To understand the likelihood that the unknown volatile was carbon dioxide, Hurley decided to explore how much carbon dioxide was needed for it to end up in a cold trap in the first place. “For every carbon dioxide molecule that you release somewhere on the Moon, what percentage of those make it to the court traps and stick there?” Hurley explained.

Using data from NASA’s LRO on the sizes and temperatures of cold traps, Hurley put together a probabilistic analysis called a Monte Carlo simulation to determine how much carbon dioxide would make it to a cold trap. “I release particles, and then follow them on trajectories,” Hurley says. She factored in the likelihood that the molecules would be broken down by sunlight before they reached a cold trap.

Hurley’s model predicted that of all the carbon dioxide released on the Moon, anywhere from 15 to 20 percent would end up in a cold trap. This was higher than previous predictions and a pretty surprising result for Hurley, considering the relatively small surface areas of cold traps.

“Just knowing exactly how small the area was where it was that cold, it’s really interesting that you can get that much carbon dioxide delivered there,” she said.

Next, Hurley plans on conducting a similar analysis for methane and carbon monoxide. More information about volatiles could guide scientists in their study of cold traps and lead to a better understanding of our celestial companion.

—Zain Humayun is a science writing graduate student at MIT.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.