8 July 2014

Livestock digestion released more methane than oil and gas industry in 2004

Posted by abranscombe

By Alexandra Branscombe

WASHINGTON, DC – Livestock were the single largest source of methane gas emissions in the United States in 2004, releasing 70 percent more of the powerful greenhouse gas into the atmosphere than the oil and gas industry, according to a new study.

The new findings based on satellite data from 2004 provide the clearest picture yet of methane emissions over the entire U.S. They show human activities released more of the gas into the atmosphere than previously thought and the sources of these emissions could be much different than government estimates.

The contribution of livestock to methane emissions was 40 percent higher in 2004 than what the federal government had previously estimated for that year based on industry reports, while emissions from the oil and gas industry were lower than these government estimates, according to the new study published last month in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, a publication of the American Geophysical Union.

Livestock, such as cows and pigs, released 70 percent more methane into the atmosphere than the oil and gas industry in 2004, according to a recent study in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. The new study also found that the EPA underestimated the amount of methane emissions from livestock for that year by 40 percent.

Credit: Flickr/kqedquest

The new findings could aid efforts to cut methane emissions, the study’s authors said. Besides carbon dioxide, methane is the most widespread greenhouse gas emitted from human activities. Although methane has a shorter lifespan in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, it is more efficient at trapping radiation, making it a powerful driver of global warming. Earlier this year, the Obama Administration released a federal strategy for cutting methane emissions from human-generated sources, including landfills, coal mines, agriculture, and oil and gas production.

“We need to know where [methane] is coming from in order to design effective emissions control policies,” said Kevin Wecht, a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., and lead author of the new study.

The new study looked at data from 2004, before the satellite instrument used to collect the data stopped working, but there is little reason to suspect that the amount of methane released by livestock has changed since that time, said Wecht. He said oil and gas production has increased since 2004, however scientists don’t know how the increased production has affected methane emissions over the entire U.S. or if methane emissions from the oil and gas industries have surpassed methane emissions from livestock.

“Studies like this in the future could reveal the extent to which increases in natural gas and oil production have influenced methane emissions into the atmosphere,” said Wecht.

The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that, in 2004, 28.3 megatonnes (31 million tons) of methane were released into the atmosphere by human activities in the United States. The EPA estimates that 8.8 megatonnes (9.7 million tons) of methane came from livestock while 9.0 megatonnes (9.9 million tons) came from the oil and gas industries.

These EPA estimates are based on a “bottom-up” approach. The EPA collects data about greenhouse gases through national energy data, information on agricultural activities, and a data reporting program that requires industries to submit their annual emissions of methane and other gases. The EPA estimates the amount of methane in the atmosphere from this data that includes information about the amount of methane each cow would produce or how much natural gas is sold, said Wecht.

The satellite tool used in the new study directly measured the amount of gas released into the atmosphere, which is more accurate than estimating methane emissions using the “bottom-up” approach, according to the paper.

The new research finds that human activities released a total of 30.1 megatonnes (33 million tons) of methane into the atmosphere in 2004. It also finds that cows and other animals emitted 12.2 megatonnes (more than 13 million tons) of the gas, which comes from belching, flatulence, and their manure. The oil and gas industries released 7.2 megatonnes (7 million tons) of methane. In comparison to carbon dioxide emissions, the U.S. electric industry, including coal, natural gas, and other energy sources, emitted over 2,039 million tonnes (2,247 million tons) of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere in 2012.

“The study showed that livestock emissions are broadly underestimated by bottom-up inventories,” said Daven Henze, an assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who was not involved in the study.

The new research uses data collected from the SCanning Imaging Absorption spectroMeter for Atmospheric CHartograph (SCIAMACHY), an instrument mounted on a satellite that measures the volume of gases in the different layers of the atmosphere. From this data, scientists can calculate the amount of methane in the atmosphere.

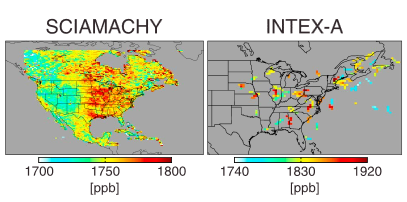

In 2004, the SCIAMACHY instrument mounted on a satellite collected methane emissions across the entire United States, displaying a complete picture of methane sources across the country(left). An airborne technique, like the INTEX-A aircraft campaign in 2004 (right), is still the current method for measuring methane in the atmosphere, but cannot provide the same coverage of the U.S. as the SCIAMACHY instrument.

Credit: AGU

The SCIAMACHY data is also more complete than the current method for directly measuring methane in the atmosphere. Traditionally, these measurements are taken by loading up airplanes with sampling tools and flying over an area that is being studied, Wecht said. Although the airborne technique can produce more accurate emissions estimates than the EPA’s “bottom-up” approach, it can’t be used to give a complete picture of emissions over the entire continent, he said.

In contrast, SCIAMACHY scans the atmospheric column directly below the satellite, covering a 960 kilometers (about 596 miles) wide swath on the ground in a single scan. The instrument is able to scan the entire globe every six days.

Comparing the methane emissions obtained by the SCIAMACHY instrument in 2004 to methane emissions from airborne sampling measurements during the same period, the scientists found that the methane data from the satellite agreed with the data taken from the airborne method. This proved that SCIAMACHY could provide the same level of accuracy as the airborne method but with higher quality, said the study.

Although the data in the study is from 2004, just before the SCIAMACHY instrument stopped working in 2005, Henze said the same methane-tracking technique could be used in the near future. A new instrument, the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI), is set to launch in 2015 and will map air pollution from space, including methane emissions. It could provide a more accurate picture of the amount of methane emitted by natural gas extraction activities, Henze said.

“The emissions from natural gas and oil production are something we suspect has changed with the increase in hydrofracking,” said Henze. “Studies like this motivate more scientists to do more research.”

– Alexandra Branscombe is a science writing intern in AGU’s Public Information department

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

1. It has recently become k own that manufacture and distribution of natural gas result in much higher releases of methane than previously understood. How does that affect the observations presented here?

2. Farmers who produce organic exclusively grass-fed beef claim that their methane production is negligible relative to methane production by cattle grown by more conventional means. Is this claim correct?

I am leaving my full name and email address and would greatly appreciate a response as I grow grass-grown organic beef perhaps based upon a misunderstanding, and have written considerably on the need for dietary changes to limit climate change.

Nicholas C. Arguimbau

[email protected]