29 May 2019

Using the past to unravel the future of Arctic wetlands

Posted by Nanci Bompey

By Anna Harrison

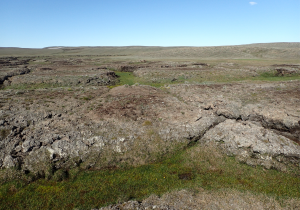

A new study has used partially fossilized plants and single-celled organisms to investigate the effects of climate change on the Canadian High Arctic wetlands and help predict their future.

The Arctic is warming faster than any other region on Earth, which is causing the region’s ecology to undergo a rapid transformation. Until now there has been limited information on the response of Arctic wetlands to climate change and rising global temperatures.

An international team of scientists led by the University of Leeds and the Geological Survey of Canada have reconstructed past moisture conditions and vegetation histories to determine how three main types of Canadian High Arctic wetlands have responded to warming temperatures over the last century.

Understanding past ecological changes in this region allows for more accurate predictions of how future changes, such as longer growing seasons and increased water from ground-ice thaw, could affect the wetlands.

The study, published in the AGU journal Geophysical Research Letters, found that under 21st century warming conditions and with adequate moisture, certain Arctic wetlands may transition into peatlands, creating new natural carbon storage systems and to some extent mitigating carbon losses from degrading peatlands in southern regions.

Study lead author Thomas Sim, PhD researcher in the School of Geography at Leeds, said: “High Arctic wetlands are important ecosystems and globally-important carbon stores. However, there are no long-term monitoring data for many of the remote regions of the Arctic – making it hard to determine their responses to recent climate warming. Reconstructing the ecological history of these wetlands using proxy evidence can help us understand past ecological shifts on a timescale of decades and centuries.”

Study co-author Paul Morris, from the University’s research centre water@leeds, said: “Our findings show that these harsh and relatively unexplored ecosystems are responding to recent climate warming and undergoing ecosystem shifts. While some of these wetlands could transition into productive peatlands with future warming, the long term effects of climate change is likely to vary depending on the type of wetland.

“Although new productive peatlands may form in places such as the High Arctic, degrading peatlands in other areas are a major global concern. Every effort should be made to preserve peatlands across the globe – they are incredibly important component of the global carbon cycle.”

The team examined ecological responses to twentieth century warming in the three types of High Arctic wetland: polygon mire, coastal fen and valley fen. Plant macrofossils and testate amoeba – tiny, single-celled organisms that live in wetlands – in combination with radiocarbon dating were used as proxies for historic changes in vegetation and moisture levels.

The study found that all three wetland types – with the exception of certain sections of the polygon mire – have experienced ecosystem shifts that coincided with an increase in growing degree days: a unit scientists use to quantify growing season length and warmth. The coastal fen site experienced an increase in shrub cover related to warming, while sections of the polygon mire increased in moss diversity.

The study also found that environmental factors other than warming temperatures may be contributing to vegetation changes. The research suggests that grazing Arctic geese may have contributed to the recent shift of from shrub to mosses in the coastal fen site. Arctic geese population have risen significantly and food competition at their summer nesting sites may be causing them to seek new grazing sites further north as they warm.

Study co-author Jennifer Galloway, Associate Professor at Aarhus Institute of Advanced Studies, Denmark and Geological Survey of Canada, said: “Our study highlights the complex ways in which climate change is affecting ecosystems and suggest that effects of climate warming will vary depending on wetland type. While we can clearly see that climate change is altering ecology across the Arctic wetlands, whether that will result in a transition to productive peatlands will be strongly influenced by the complex dynamics that govern the wetlands.”

— Anna Harrison is a press officer at the University of Leeds. This post originally appeared as a press release on the University of Leeds website.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.