22 April 2019

New research explains why Hurricane Harvey intensified immediately before landfall

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

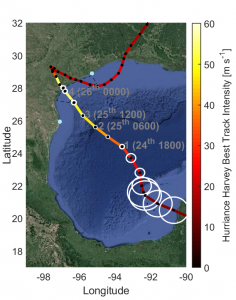

This image shows Hurricane Harvey’s track and intensity as it passed through the Gulf of Mexico and made landfall along the Texas coast. Harvey intensified from a Category 1 storm to a Category 4 as it crossed the Gulf of Mexico and entered the Texas Bight on August 24 and 25.

Credit: Potter et al. 2019/Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans/AGU.

By Lauren Lipuma

A new study explains the mechanism behind Hurricane Harvey’s unusual intensification off the Texas coast and how the finding could improve future hurricane forecasting.

Hurricanes are fueled by heat they extract from the upper ocean. But hurricane growth often stalls as the storms approach land, partly because as the ocean gets shallower, there is less water and therefore less heat available to the storm. As a result, most hurricanes weaken or stay the same strength as they get close to making landfall.

But Hurricane Harvey intensified from a Category 3 storm to a Category 4 as it neared the Texas shore in late August 2017, and scientists have been puzzled as to why it was different. In a new study, researchers at Texas A&M University compared ocean temperatures in the Texas Bight, the shallow waters that line the Gulf Coast, before and after Harvey passed through it.

They found the Bight was warm all the way to the seabed before Harvey arrived. Strong hurricane winds mix the ocean waters below the storm, so if there is any cold water below the warm water at the surface, the storm’s growth will slow. But there wasn’t any cold water for Harvey to churn up as it neared the coast, so the storm continued to strengthen right before it made landfall, according to the study’s authors.

“When you have hurricanes that come ashore at the right time of year, when the temperature is particularly warm and the ocean is particularly well-mixed, they can absolutely continue to intensify over the shallow water,” said Henry Potter, an oceanographer at Texas A&M and lead author of the new study in AGU’s Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans.

The researchers don’t yet have enough temperature data to say if the Texas Bight was unusually warm in 2017. But the findings suggest hurricane forecasters may need to adjust the criteria they use to predict storm intensity, according to Potter. Forecasters typically use satellite measurements and historical data to make intensity predictions, but Harvey’s case shows they need data collected from the ocean itself to know exactly how much heat is there, where that heat is located in the water column and if it’s easily accessible to the storm, Potter said.

Lauren Lipuma is a senior public information specialist at AGU. Follow her on twitter at @Tenacious_She.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.