24 January 2018

Stored heat released from ocean largely responsible for recent streak of record hot years

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

By Lauren Lipuma and Mari N. Jensen

Global temperatures spiked during the record warm years of 2014 to 2016 largely because El Niño released an unusually large amount of heat generated by greenhouse gas emissions and stored in the Pacific Ocean, a new study finds.

2014, 2015 and 2016 were the warmest consecutive years since temperature records began in 1880, according to data from NASA and NOAA. Earth’s average surface temperature rose by about 0.9 degrees Celsius (1.6 degrees Fahrenheit) from 1900 to 2013, but temperatures jumped an additional 0.24 degrees Celsius (0.43 degrees Fahrenheit) from 2014 to 2016, according to the new study.

By analyzing records of global temperature, sea level rise, ocean heat content and other climate data, the study authors find the 2015-2016 El Niño released excess heat from the Pacific Ocean that had accumulated over the past two decades because of global warming.

They conclude this heat transfer from the ocean is largely responsible for the sharp spike in temperatures.

“Our paper is the first one to actually quantify this [temperature] jump and identify the fundamental reason for this jump,” said Jianjun Yin, an associate professor of geosciences at the University of Arizona in Tucson and lead author of the new study in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

This animation shows how global temperatures have changed since 1880.

Credit: NOAA.

“As a climate scientist, it was just remarkable to think that the atmosphere of the planet could warm that much that fast,” said climate scientist Jonathan Overpeck, Dean of the School for Environment and Sustainability at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and co-author of the new study.

The record-breaking temperatures from 2014 to 2016 coincided with extreme weather events worldwide, including heat waves, droughts, floods, extensive melting of polar ice and global coral bleaching. The study authors predict that temperature spikes like the one from 2014 to 2016 and accompanying extreme weather events will become more frequent by the end of the century unless greenhouse gas emissions decline.

“Our research shows global warming is accelerating,” Yin said.

Connecting the ocean with the atmosphere

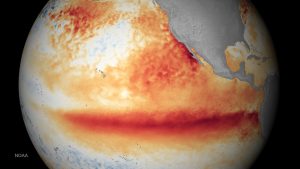

Pacific Ocean sea surface temperatures, measured here in November 2015, surged during the 2014-2015 El Niño. New research finds this El Niño released excess heat stored in the Pacific Ocean since the 1990s.

Credit: NOAA Environmental Visualization Laboratory.

Greenhouse gas emissions have continued to rise, but Earth’s surface warming slowed down from 1998 to 2013. Previous research by study co-author Cheryl Peyser, Yin and colleagues has shown the Pacific Ocean had been storing excess heat from the atmosphere during these years and that the 2015-2016 El Niño had released that stored heat. El Niño is the warm phase of a recurring climate pattern across the tropical Pacific Ocean called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO.

In early 2017, Yin and Overpeck were having lunch when Yin mentioned how fast global temperatures had increased over the past several years.

“I knew it was warming a lot, but I was surprised at how much it warmed and surprised at [Yin’s] insight into the probable mechanism,” Overpeck said.

The two scientists then began brainstorming about expanding on Yin and Peyser’s previous work.

In the new study, the researchers analyzed observations of global surface temperatures from 1850 to 2016, ocean heat content from 1955 to 2016, sea level records from 1948 to 2016 and records of the El Niño climate cycle and a longer climate cycle called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation—15 different datasets in all.

Their analysis showed the 0.24 degree-Celsius (0.43 degree-Fahrenheit) global temperature increase from 2014-2016 was unprecedented in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Some heat transfer from the Pacific Ocean to the atmosphere is normal during an El Niño. But the researchers found the temperature increase from 2014 to 2016 was so large because El Niño released excess heat the Pacific Ocean had been storing since the 1990s because of increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

The planet’s long-term warming trend is seen in this chart of every year’s annual temperature cycle from 1880 to the present, compared to the average temperature from 1980 to 2015. Record warm years are listed in the column on the right.

Credit: NASA/Joshua Stevens, Earth Observatory.

“The result indicates the fundamental cause of the large record-breaking events of global temperature was greenhouse-gas forcing rather than internal climate variability alone,” Yin said.

Predicting future temperature change

The researchers also projected how often global temperature surges of 0.24 degree-Celsius (0.43 degree-Fahrenheit) or greater might occur in the 21st century. To predict how often such a jump would occur, the team looked at future climate projections based on different scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions.

The projections indicate that if greenhouse gas emissions peak by 2020 and decline thereafter, temperature jumps of at least 0.24 degrees Celsius (0.43 degrees Fahrenheit) might occur once in the 21st century or not at all.

But if greenhouse gas emissions rise unabated throughout the 21st century, the projections suggest large temperature surges would occur three to nine times by 2100. Under this scenario, such events would likely be warmer and longer than the 2014-2016 spike and have more severe impacts. Adapting to more frequent and intense rapid warming events like these will be difficult, according to the researchers.

“If we can reduce greenhouse gas emissions we can reduce the number of large record-breaking events in the 21st century—and also we can reduce the risk,” Yin said.

— Lauren Lipuma is a senior public information specialist and writer at AGU. Mari N. Jensen is a senior science writer and public information officer at the University of Arizona. This post originally appeared as a press release on the University of Arizona website.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

The mechanism for oceanic to atmosphere heat transfer is far more complex. During La Niña years, cloud cover over the Equatorial Pacific is markedly increased. Incoming solar radiation is immediately reflected at wavelengths that CO2 cannot intercept, so the planet cools. Half of the heat released from the oceans is then redirected downward and re-absorbed and retained in the oceans by the clouds themselves. When El Niño shows up Equatorial Pacific cloud cover diminishes, allowing released heat to transfer to the atmosphere, adding to atmospheric warmth. This is the short version, and there are a far greater complexities that need to be considered. Oversimplification of the intricacies involved is not helpful.

The heat from major El-Ninos (1997) causes CO2 to leave the surface oceans and appear in the atmosphere during the following cold La-Ninas (1998). Not the reverse. This has been the case at least since the 1982-84 ENSO. The “soda bottle effect.”? But, regardless, we cannot reduce emissions, transition to solar and wind and then expect to take hundreds of billions of tons of CO2 from the atmosphere using those energy sources. Hundreds of years, giga-currencies. Talk about risks?