21 July 2017

Mountain glaciers recharge vital aquifers

Posted by ksimpkins

By Meghan Murphy

UAF researchers grab a water sample for geochemical analysis at the mouth of the Jarvis Glacier.

Credit: Todd Paris

Small mountain glaciers play a big role in recharging vital aquifers and in keeping rivers flowing during the winter, according to a new study published in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

The study also suggests that the accelerated melting of mountain glaciers in recent decades may explain a phenomenon that has long puzzled scientists – why arctic and subarctic rivers have increased their water flow during the winter even without a correlative increase in rain or snowfall.

“I think that mountain glaciers in the Arctic and subarctic have really been under appreciated as a source of water to the landscape,” said Anna Liljedahl, the lead author and an associate professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Water and Environmental Research Center.

Liljedahl and her coauthors at the U.S. Geological Survey and Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory studied a watershed in a semidry climate in the eastern Alaska Range that includes the community of Delta Junction. The team looked at how melt water from two small mountain glaciers flowed through the system and influenced the mountain streams, rivers and groundwater all year long.

University of Alaska Fairbanks researcher Anna Liljedahl cores the glacier snow pack on Jarvis Glacier to measure snow density in order to estimate how much water is stored in the later winter snow pack before the snow melts.

Credit: Todd Paris

Through extensive field measurements, the team found that Jarvis and Gulkana glaciers contributed 15% to 66% to the annual flow of mountain streams that connect the glaciers to the Delta River. Yet when the team compared the volume of water at an upper site and 55 km downstream of one of the major mountain streams, they found that the stream lost half its water to an aquifer storing groundwater.

“These headwater streams, coming off the mountains and into the lowland, are like the water line to your house peppered with holes, half of the water disappearing into the ground and recharging your neighbor’s house well instead of it all reaching your kitchen faucet,” she Liljedahl.

Liljedahl said the recharge of the aquifers is important because they don’t freeze during the winter and are the only source of water to the rivers during this time. In Delta Junction, the water table drops more than 10m each winter as the aquifers leak water to the almost 600-mile Tanana River, which the Delta River drains into.

Liljedahl said this is a process that has probably been going on thousands of years. Yet recent temperature gains in climate may be accelerating the glaciers’ melting and thereby introducing more meltwater into aquifers and then the rivers.

“The winter discharge of the Tanana River has increased since the record keeping began in the 70’s, but there are no increasing trends in precipitation,” she said. “Glacier coverage has, on the other hand, decreased by 12% and that is more than plenty of additional water to explain the increase in river base flow. In fact, about five times more.”

But it may not be long before this process ends all together, she said. The glaciers are disappearing or shrinking to very high elevations where colder temperatures slow melting. As glacier melt decreases, so may the streamflow if there is not enough water to both feed both the aquifer and the stream.

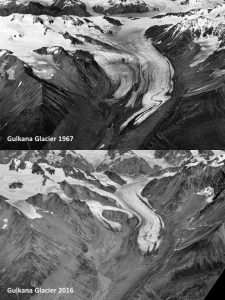

Between 1967 (top photo) and 2016 (bottom photo), the Gulkana Glacier has lost a volume of ice equivalent to a layer of water more than 80 feet deep across its current area. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

Co-author Shad O’Neel, a researcher with the Alaska Science Center at the U.S. Geological Survey, said this study shows another way that glaciers are connected to the ecosystem and to human processes in the Arctic.

“Although the traditional focus of glaciology has been on sea level rise, we are rapidly discovering that the small mountain glaciers may have large impacts on human populations,” he said. “Across the globe, the mountain glaciers influence ecosystem processes like stream flow, nutrient delivery and primary production in the ocean. Human implications range from drinking and agricultural water supplies to recreation and tourism. ”

Liljedahl said she is currently researching the role of mountain glacier melt in the water cycle in other semi-arid landscapes such as the Russian and Canadian Arctic. If the process holds true in these places, she said, then tiny mountain glaciers may be helping power watersheds throughout large portions of the Arctic.

“I think people have assumed that these tiny glaciers are not important because they’re tiny, but we’re in a climate where we have very little precipitation,” she said. “Any additional water can make a big splash.”

National Science Foundation funded much of the research.

— Meghan Murphy is a Public Information Officer and Recruitment Coordinator at the College of Natural Science and Mathematics at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. This post originally appeared as a press release on the University of Alaska Fairbanks website.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.