19 September 2016

Ms. Callaghan’s Classroom: Multi-coring

Posted by larryohanlon

This is the latest in a series of dispatches from scientists and education officers aboard the National Science Foundation’s R/V Sikuliaq. Jil Callaghan is a 6th grade science teacher at Houck Middle School in Salem, Oregon. She is posting blogs for her students while aboard the Sikuliaq as part of a teacher at sea program through Oregon State University. Read more posts here. Track the Sikuliaq’s progress here.

By Jil Callaghan

Dated: 15 September 2016

Getting to the Bottom of What’s Happening in the Arctic Ocean

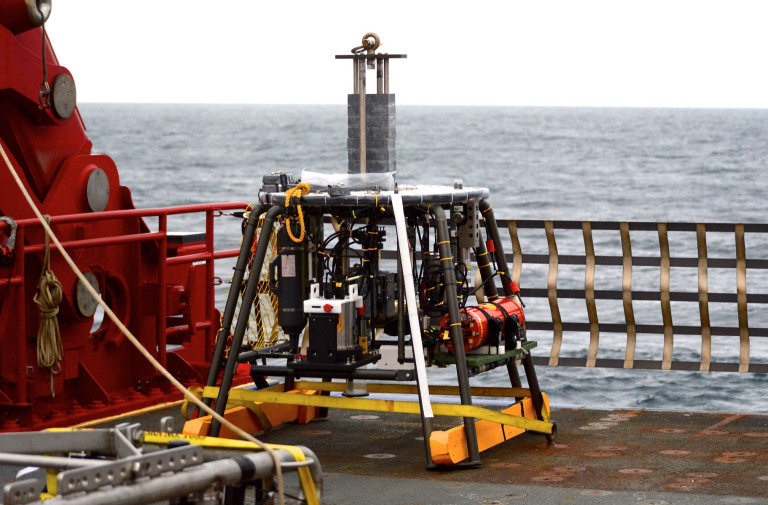

Yesterday we did our first deployment of a piece of science equipment that is called a multi-corer. I got to help out and had fun! First you have to wear what’s called a big orange “float coat” that will help you stay afloat if you go overboard, but it also helps keep you warm🙂 You also have to put on a hard hat. In the photo above, I got to help pull the multi-corer back towards the ship – we use hooks to attach ropes to loops on the multi-corer.

While we were waiting outside in the below-freezing cold for the multi-corer to be ready, I took advantage of the warm deck. The deck floor is heated to prevent any ice from forming – they call it the “steel beach.”

What’s a multi-corer?

A multi-core is a piece of scientific equipment that we send down to the bottom of the ocean where it drives 4 tubes into the sediment layers down there. As we lift it up, it snaps shut, giving us tubes with “cores” of the sediment (mud) at the bottom of the sea. It also has a CTD tube to collect water, measure temperature, and salinity; an altimeter to measure pressure and depth; as well as a very expensive curved lens for the camera; and 2 lasers.

The multi-corer is strapped down to the deck while we move to the next location where we’ll take samples.

The operations of the Sikuliaq depend heavily on a well-trained crew to operate all the machinery and assist with data collection. (I’m on the far right)

What does the mud tell us?

Dr. Miguel Goñi from OSU is looking for evidence of animals and plants that have died and fallen to the ocean floor. Looking at what is on the ocean floor gives us an idea of what has been growing and living in the water up above. Based on the rate at which sediment falls to the bottom, and the depth of the samples we collect (some of that mud down there is very thick, like clay, and hard to push through), our samples can tell us what’s been happening for the last 200 years!

One thing that we can see evidence of is phytoplankton blooms – where the ocean currents bring nutrients (food) and the phytoplankton (microscopic marine plants) suddenly grow like crazy – called a “bloom”. After they use up the nutrients they die, and some will fall down all the way to the bottom of the ocean (others will be eaten before they reach the bottom). This layer of dead phytoplankton as evidence of blooms is one of the things that Dr. Goñi is looking for in his core samples.

Dr. Miguel Goñi of OSU cutting a core sample. The cores are cut into layers 1 cm thick by placing a 1 cm tall plastic ring on top before we push the mud up. We cut between the plastic ring and the tube.

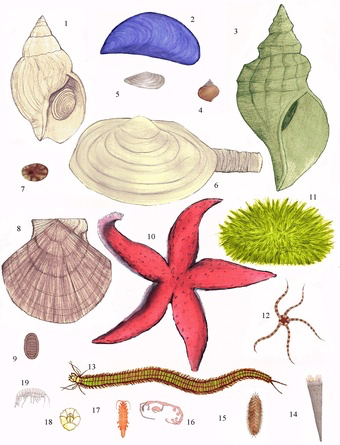

We found all kinds of critters in the mud, including benthic amphipods (#19 in the illustration below), isopods (17), scaleworms (15), tube worms (not shown in the illustration), as well as brittle stars (12) on the surface layer.

The above illustration shows various benthic animals: 1. common whelk, 2. blue mussel, 3. Neptune whelk, 4. periwinkle, 5. Yoldia hyperborea, 6. sand gaper, 7. limpet, 8. scallop, 9. chiton, 10. common starfish, 11. green sea urchin, 12. brittlestar, 13. ragworm, 14. pectinaria worm, 15. scaleworm, 16. skeleton shrimp, 17. isopod, 18. barnacle, 19. benthic amphipod.

It was so cool to watch pieces of ice float by as we were working on deck! I’m standing next to the hose because we wash off the utensils (the metal sheet for cutting, the spatula used for scraping it into the bag, and the plastic ring) in between samples so that we don’t contaminate one layer with mud from another!

For each sample, we make sure that we know which cruise it was, where it was taken from, and how deep down from the surface the sediment is from. The sediment samples will be analyzed back in Dr. Goñi’s lab at OSU.

This post was originally published on thedynamicarctic.wordpress.com

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.