15 December 2015

One Million Icequakes

Posted by lhwang

An unusual glacier brings scientists closer to understanding how flowing ice impacts sea level rise

Researchers work in Greenland to instill seismic activity detectors, buried into glacier sediment.

Credit:Timothy Bartholomaus

by Bethany Augliere

Nestled in the Arctic is a glacier like no other. This glacier quakes once a minute creating seismic events that rattle the earth—more frequently than scientists have ever seen. Understanding why these icequakes are so common may help researchers predict future ice flow, a process that propels climate-driven sea level rise.

Glaciers and ice sheets are rapidly shrinking around the world, particularly those that melt into the ocean, and faster-melting glaciers lead to faster sea level rise. Studying seismic signals from glacier motion could help scientists understand the short-term factors that contribute to the larger scale motion of glaciers and ice sheets, said Timothy Bartholomaus, a glaciologist at the University of Texas.

“To make better predictions of how ice flow is going to occur in the future, we have to have that mechanistic understanding of how ice flows now,” Bartholomaus said.

Bartholomaus and scientists from the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics and the University of Kansas have detected over one million icequakes produced by a single Greenland glacier named Kangerlussuup Sermia, or KS for short. They reported the results from a study of the glacier at the 2015 American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting.

“This is not something that has been seen at other glaciers,” Bartholomaus said. “Other glaciers produce seismic signals, but not nearly this frequently.”

KS spans 100 kilometers from the interior of the Greenland Ice Sheet to fjords off the country’s west coast. To detect icequakes, the scientists buried three soup-can sized seismometers that measure how fast the ground shakes. The first was deployed in 2013 and collected data for two years.

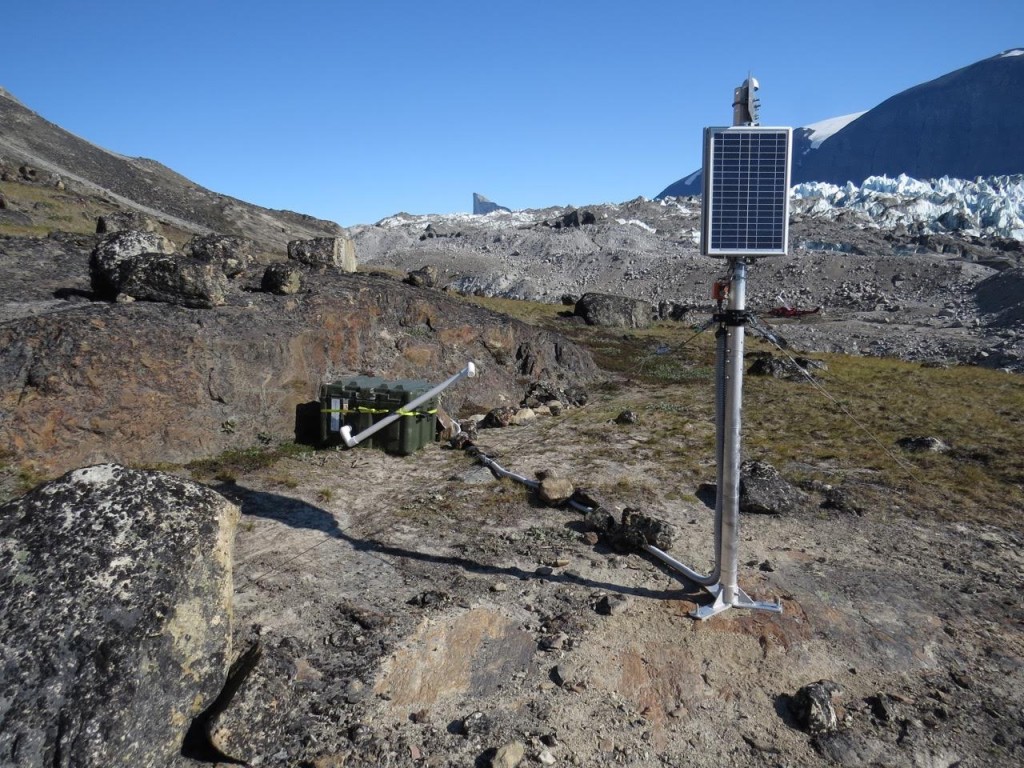

The seismometer sensor is buried underground, with surface – supplied batteries, GPS, and solar panels to record timing of icequakes.

Credit:Timothy Bartholomaus

Bartholomaus is interested in the factors that control glacier melt and flow into the ocean. His team didn’t set out to study icequakes, but their instruments detected them: 20 icequakes every 60 seconds for two years.

That’s a million quakes, Bartholomaus said, “which is an incredible amount of activity.”

Regular tectonic earthquakes aren’t this predictable and even, he said. And for glaciers, many processes can result in seismic activity, including water flowing at the base and ice cracking at surface, he added.

“You can imagine that glaciers are flowing down under the influence of gravity, and there are various factors that are holding them back, so they don’t just zip along at Mach speeds,” he said.

In this case, the quakes may be related to friction. Resistance can come from any direction: the ground beneath the glacier, the side, the front, or the back, Bartholomaus said. For most glaciers, friction comes from beneath, but not for this one. KS is a slippery glacier, but researchers don’t know why. Lack of friction could cause the quakes, as the glacier’s underside catches the rocky sediment below, according to Bartholomaus.

And every time the ice catches it fractures, producing a little quake, he said.

Researchers are excited to study icequakes because they offer a window into the glacier bed where ice meets the sediment, according to Bartholomaus.

“We can observe the top of the glacier, but the bottom is almost entirely inaccessible,” he said.

‑ Bethany Augliere is a graduate student in the Science Communication program at UC Santa Cruz. You can follow her on twitter at @BethanyAugliere

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.