15 December 2010

Turning back the clock of human arrival in Alaska’s interior

Posted by mohi

Humans are thought to have first migrated to North America from Asia over the Bering land bridge into modern day Alaska. Eventually, these peoples moved inland and southward as they began to colonize the rest of North America. The first steps of human migration into the rest of the continent can be seen in the early human settlements of the interior of Alaska. A study presented in one of yesterday morning’s poster session shows that human occupation of central Alaska happened earlier than previously thought.

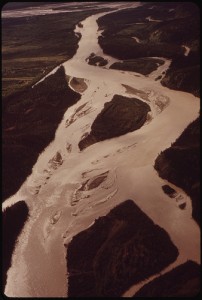

Archaeological sites from the Alaska's Tanana River valley may help scientists understand early human migration patterns. Image courtesy of EPA and US National Archives

In GC21C-0884 “Stable-Isotope Perspectives on Holocene Environmental Change at Archaeological Sites in the Middle Tanana Valley, Interior Alaska,” Bill Johnson of the Department of Geography at the University of Kansas described a study of the Tanana River Lowlands in central Alaska. Humans inhabited ridges above the marshy wetlands along the Tanana River, a branch of the Yukon River. By sampling the sediments at these sites, Johnson and colleagues found that humans occupied the area about 1500 years earlier than previously thought.

They found human artifacts, including microscopic remnants of charcoal made by man-made fires, in sediment layers as old as 13,470 years. Previous studies of human occupation in the area had estimated human arrival around 12,000 years ago.

Johnson and colleagues also studied carbon and nitrogen isotopes of their samples and found that starting around 13,000, the plants in the region transitioned from cold tolerant grasses to more trees like spruce and birch.

The team also found phytoliths–“plant stones”–in their samples. Phytoliths are hard mineral formations that can build up in plants if the waters that nourish them contain high amounts of dissolved silica. The shape and size of phytoliths can tell researchers about the type of plant that made them. In this case, the phytoliths found throughout the sediment layers also pointed to a transition from cold-tolerant grasses to trees.

By defining the timing and character of environmental change along the Tanana River, including changes in vegetation, the researchers hope to better understand the archaeological record of early human occupation in the interior of Alaska.

–Susan Young is a science communication graduate student at UC Santa Cruz

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.