10 February 2016

How stable is the West Antarctic Ice Sheet?

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

Exceeding critical temperature limits in the Southern Ocean may cause the collapse of ice sheets and a sharp rise in sea levels, a new study finds

By Folke Mehrtens

Shelf ice edge in the Atka Bay, eastern Weddell Sea, off the coast of West Antarctica.

Credit: Alfred Wegener Institute/Stefan Hendricks.

A future warming of the Southern Ocean caused by rising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere may severely disrupt the stability of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which would raise sea levels by several meters, according to new research. A temperature increase of 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) would be enough to initiate irreversible melting of the ice sheet, the new study found.

“Given a business-as-usual scenario of global warming, the collapse of the West Antarctic [Ice Sheet] could proceed very rapidly and the West Antarctic ice masses could completely disappear within the next 1,000 years,” said Johannes Sutter, a climate scientist at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) in Bremerhaven, Germany, the study’s lead author.

Antarctica and Greenland are covered with ice sheets that together store more than two-thirds of the world’s fresh water. If temperatures rise, these ice masses could melt, which would raise sea levels and threaten coastal regions, but how ice responds to warming temperatures in the Antarctic is not yet fully understood.

In the new study, Sutter and colleagues used climate models to analyze changes in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet during the last interglacial period, when sea levels were about seven meters (23 feet) higher and polar surface temperatures were around 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) higher than today.

Cascade of meltwater, partly frozen while flowing, at the shelf ice edge of Larsen A, western Weddell Sea, off the coast of West Antarctica.

Credit: Alfred Wegener Institute/Wolf Arntz.

Previous research has shown that melting of the Greenland ice sheet alone could not have raised sea levels this much, said Gerrit Lohmann, a co-author of the study.

The researchers found that a collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet may have occurred during that interglacial warming period. Their results were recently accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

Based on their model calculations, the ice masses of West Antarctica shrink in two phases. During the first phase, ice shelves – ice masses that float on the ocean in coastal areas – retreat. If the ice shelves are lost, ice and glaciers on the adjoining land also retreat and more ice flows into the ocean. As a result, the sea level rises and the grounding line – the boundary between the floating ice shelf and ice on land – retreats.

A mountain ridge under the grounded ice would temporarily slow down the retreat of the ice. But if ocean temperatures continue to rise or if the grounding line reaches a steeply ascending subsurface, then the glaciers would continue to retreat. Ultimately, this leads to a complete collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. This collapse could explain the high sea levels seen during the interglacial period, Sutter said.

The new findings on the past dynamics of the ice sheet allow scientists to draw conclusions about how it might behave in the wake of global warming, according to the study’s authors.

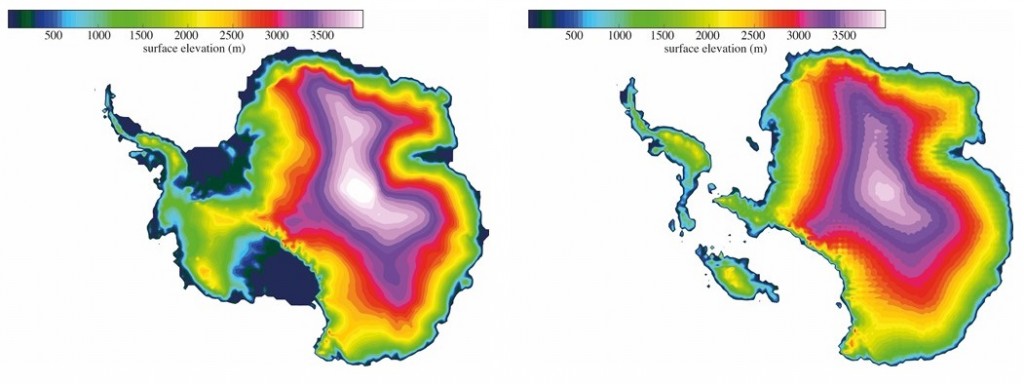

Left: Antarctica’s topography today. Right: A model of Antarctica’s topography with a collapsed West Antarctic Ice Sheet during the last interglacial period.

Credit: Alfred Wegener Institute/Johannes Sutter.

“Both for the last interglacial period around 125,000 years ago and for the future, our study identifies critical temperature limits in the Southern Ocean,” Sutter said. “If the ocean temperature rises by more than 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) compared with today, the marine-based West Antarctic Ice Sheet will be irreversibly lost.”

If climate change continues as it has up to now, this would lead to a significant Antarctic contribution to sea level rise of three to five meters (10 to 16 feet), Sutter said.

According to the researchers, an improved understanding of the interaction between climate and ice sheets is crucial to answering one of the central questions of current climate research and for future generations: how steeply and, above all, how quickly can the sea level rise in the future?

– Folke Mehrtens is a press officer at AWI. This post originally appeared as a press release on the AWI website.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.