6 August 2012

As Curiosity’s wheels touch down, science gets rolling

Posted by kramsayer

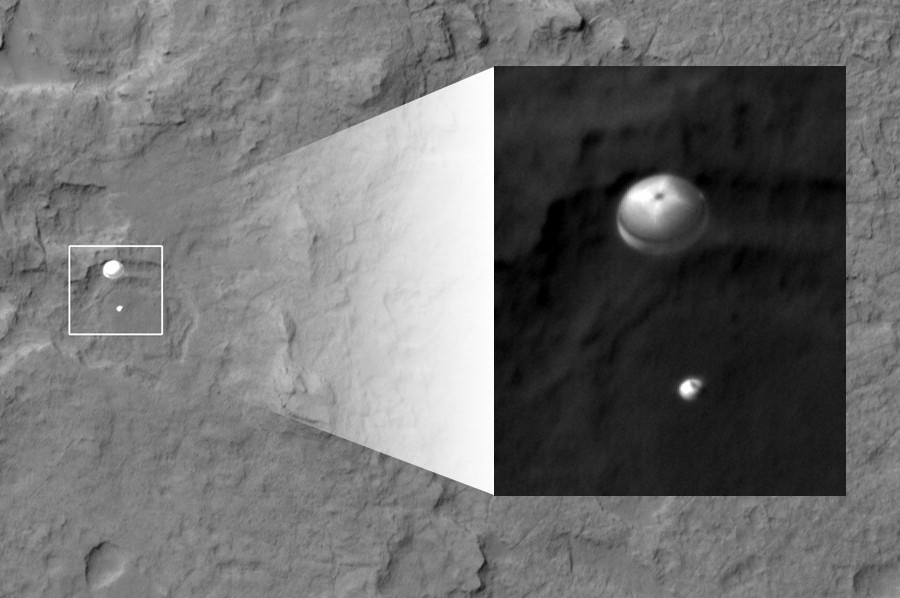

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter snapped a high-resolution image of NASA's Curiosity rover, and its parachute, just before it landed safely on Mars at 10:31 p.m. PDT Sunday. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

As viewing parties celebrating the successful landing of the Mars Science Laboratory wound down early Monday morning, 400 scientists – many of them AGU members – were already using their newest tool for investigating the red planet.

The scientists who will guide the geology, chemistry, mineralogy and other studies of NASA’s latest Mars rover got to work scanning the initial images from the rover to see what they could discover about its landing site. And in the coming days, they will focus on testing out the complex instruments on the 1,982-pound rover, also known as Curiosity.

“It’s the biggest robotics system we’ve ever put down. There’s lots of checking (the rovers’ instruments) out, turning on the instruments,” said Raymond Arvidson, with the Washington University in St. Louis, who will be working on the rover’s mobility and other projects. “The science for the first week is pretty well all defined.”

Curiosity’s drivers will ensure the wheels can twist and turn as designed. Other rover operators will deploy the mast and test the navigation cameras as well as the rock-analyzing laser. Perhaps the rover will scoop up some soil, collecting data about the Martian landing site, said Arvidson, an AGU Fellow.

And the science team will be eagerly pouring over every new image from the site, making plans for the rover’s first trip, said Melissa Rice, a member of the geology team for the Curiosity mission and a post-doctoral student at Caltech, as well as an AGU member.

“Once we know we have a fully functioning rover, then the real science part of the mission starts,” she said.

One major destination will be Mount Sharp – a 5-kilometer (3-mile) high peak with layers of different rocks, Arvidson said.

“It’s like driving through geologic time,” Arvidson said, noting that scientists might be able to decipher fundamental changes in ancient Martian climates, from lake beds to a desert-like environment. The rover’s suite of instruments aren’t designed to detect life, he said – unless the robotic explorer scoops up a fossil. But Curiosity should be able to collect data on Mars’ ancient geochemical environment and look for traces of organic compounds that could indicate an environment friendly to simple life.

One of the first images from Curiosity shows the Martian plain where the rover landed. Future images from the rover will include the first true-color shots from the red planet. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The Curiosity mission has a chance to tackle some of the big questions that have been around since the Viking missions in the 1970s, said Sean Solomon, director of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, New York, and also the principal investigator for NASA’s MESSENGER mission to Mercury. Solomon was the president of the American Geophysical Union from 1996 to 1998.

“Are there organic materials on Mars? And, if the answer turns out to be yes, were there habitats that could have been cradles for the genesis of life independently of life on Earth?” Solomon asked.

While Curiosity might not be able to address the latter question directly, he said, its location in Gale Crater is a promising environment in which to find carbon-based compounds like amino acids, simple proteins, sugars, and other materials similar to the building blocks of life on Earth.

“If we see those on Mars, at least we can ask the question: ‘What were the differences in environments between Mars and Earth?’” Solomon said.

At a news conference this morning, John Grotzinger, Curiosity’s project manager, said that the science team had been able to decipher a limited amount of information from the initial pictures from the rover.

“Most people felt that we’re on a gravel plain of Mars,” he said.

The rover may have landed close to an alluvial fan that has been mapped by satellite, said Nicolas Mangold, another science team member from the University of Nantes in France. The scientists are now seeing small pebbles and gravels, which could be interesting for geomorphology and mineral studies.

And there will be exciting developments over the next three to four months, as the rover explores its landing area, said Mangold, also an associate editor for the Journal of Geophysical Research-Planets – and some initial discoveries should be ready in time for AGU’s Fall Meeting in December 2012.

For Mangold, though, the most important questions the rover could help scientists answer involve finding out more about the climate and aqueous history of the red planet. And while it might take Curiosity several months to a year or so to get to the clay-rich layers that might provide clues – Sunday’s landing was great enough to last until then, he said.

When Mars Science Laboratory touched down on the surface of the Red Planet late Sunday night, the scientist teams had gathered at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to watch baited breath.

“Most people were like myself, we couldn’t sit down or sit still for that,” Rice said. “There was standing and pacing and wringing of hands, a lot of nervous excitement.”

All attention was focused on the tremendous engineering feat of landing the rover safely.

“Amazingly, all that happened perfectly,” Arvidson said. “It was a great thing to see happen.”

-Kate Ramsayer, AGU science writer

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.