3 August 2012

Two Mars scientists prepare for Curiosity’s descent to the red planet

Posted by mcadams

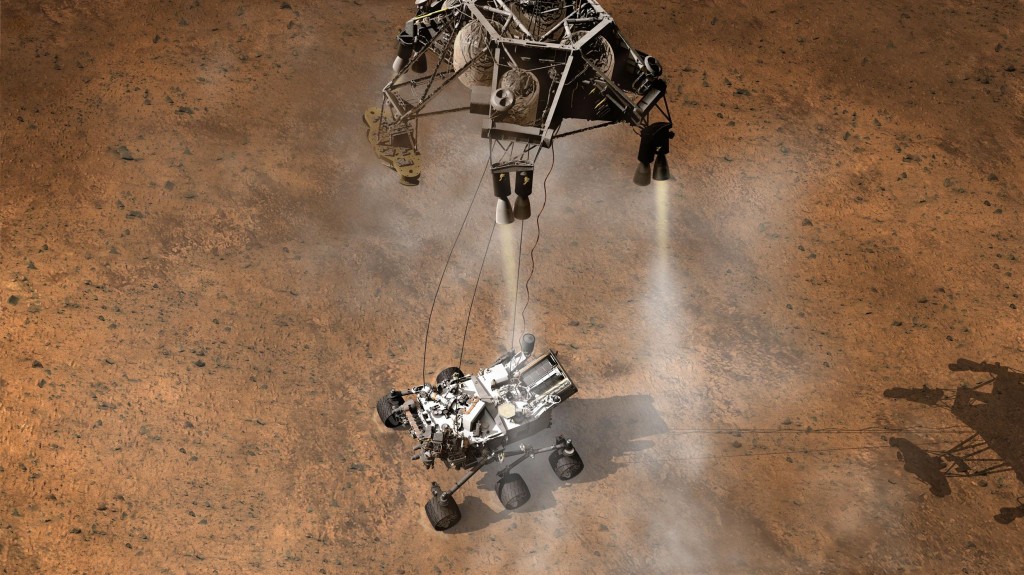

This artist's depiction of the Mars Science Laboratory, also known as Curiosity, shows the rover at the moment it touches down on the surface of Mars. Photo credit: NASA.Two young AGU member-scientists balance nervousness with excitement over the imminent arrival of the Mars Science Laboratory, a.k.a. “Curiosity,” on the planet’s surface.

Two young AGU member-scientists balance nervousness with excitement over the imminent arrival of the Mars Science Laboratory, a.k.a. “Curiosity,” on the planet’s surface.

For Ryan Anderson the journey beginning next week in Mars’ Gale Crater dates back several years when his graduate school advisor asked him, “Hey, you want to look at [Mars] landing sites? Here’s a cool one!” Building on other researchers’ previous studies, Anderson’s subsequent work at Cornell University, which led to his PhD, helped to convince mission planners that the crater would make for an ideal landing site.

Anderson and several hundred scientists are descending upon NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory outside Pasadena, California this weekend for the landing of the Mars Science Laboratory. The rover is scheduled to touch down this Sunday at 10:31 p.m. Pasadena time, or 1:31 a.m. Monday morning on the East coast.

The great thing about Gale, Anderson said, is the mountain in the middle of the crater. Its rock and soil layers act like a time capsule of Martian history. Working through the mountain’s layers, Curiosity will test each for evidence of habitability. A home run, Anderson said, would be detecting organic compounds, but success could also come from finding evidence that water with the right salinity and acidity was around long enough for life to get a foothold.

Because it takes just under 14 minutes for transmissions from Mars to make the 248-million-kilometer (154-million-mile) journey to Earth, Curiosity’s creators – along with the rest of the world – won’t get word that the rover has started its descent until after it has already landed.

Once the rover lands, Anderson, currently a post-doc at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Astrogeology Science Center in Flagstaff, Ariz., will study data returned by the rover’s ChemCam, an instrument that zaps rocks with a laser from up to seven meters (more than 20 feet) away to determine their chemical composition.

Melissa Rice works at a Science Operations Working Group meeting for the Mars Exploration Rovers at Cornell University a few years ago. Rice will be analyzing data from the Mars Science Laboratory after it lands on Sunday. Photo credit: Casey Dreier.

Also, eager to see how things go in the next few days, Melissa Rice admits to being “a little nervous and more than a little excited” about Curiosity’s descent. A post-doc who moved to the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena to work on the rover team after finishing her PhD at Cornell a few months ago, Rice says she expects Curiosity “to land and be an enormous success and to continue operating well beyond its nominal two-year schedule.” Still, she adds, “I have to remind myself that not every mission is a success.

Rice will be part of the geology group on the Curiosity team, working beside other scientists to analyze the data returned by the rover. She’ll also spend time as the team’s documentarian, creating detailed records of the scientists’ plans for the rover.

“I’ve been reared in a generation of Mars scientists that has been incredibly fortunate to have successful missions on the ground operating for far longer than their primary mission timeline. Since I started grad school the MERs have been working continuously and returning data,” she said, referring to NASA’s Mars Exploration Rovers (MERs) Spirit and Opportunity, which landed separately in January of 2004. Opportunity’s mission, designed to last just 90 Martian days, is still ongoing.

While Anderson prepares for the data to come from the Martian surface, he’s already exploring some of the emotional terrain touched upon by previous missions in entries on his blog The Martian Chronicles, part of the AGU Blogosphere. In a recent post, he explored the feelings of sadness some people feel at the thought of these droid-like creatures being abandoned on another planet.

Remember, he urges readers, Mars is Curiosity’s home.

“We try not to personify too much, but at the same time, it’s hard not to,” Anderson said. “People feel bad about sending the rovers to Mars, but (a) they’re machines and they don’t care, and (b) they work better on Mars.”

Ryan Anderson, author of The Martian Chronicles on the AGU Blogosphere, speaks at an AGU Fall Meeting bloggers' lunch. Photo credit: American Geophysical Union (AGU).

If you feel bad for the rover, he said, just think of how liberating it will be for it to be going “home,” where it can finally stretch out its arm all the way, no longer bound by Earth’s stronger gravity that prevents the rover’s heavy arm from extending fully on our home planet.

All of these hopes assume that the rover actually makes a successful touchdown. The landing technique is a first for NASA, which describes the unique descent as “Seven Minutes of Terror.” The rover, tucked in a vaguely disc-shaped capsule, will go through a series of steps to slow it for a safe landing on the surface. Decelerated first by the thin Martian atmosphere, the rover will then be slowed by a parachute, rockets, and finally, a ‘sky crane’ designed to gently lower it via a tether to the surface.

For now, Rice, Anderson and their colleagues have just one more weekend before Curiosity’s first day on the red planet.

“It’s very exciting. It’s sort of hard to even process that we are about to be landing on Mars. We’ve been building up to this for so many years…and now it’ s all finally coming to a head,” Anderson said. “It’s like the birth of a child… You think you’re prepared for it but then the day comes.”

– Mary Catherine Adams, AGU public information specialist

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.