23-Storied careers: Auroras, deadly radiation, and Earth’s long-term future

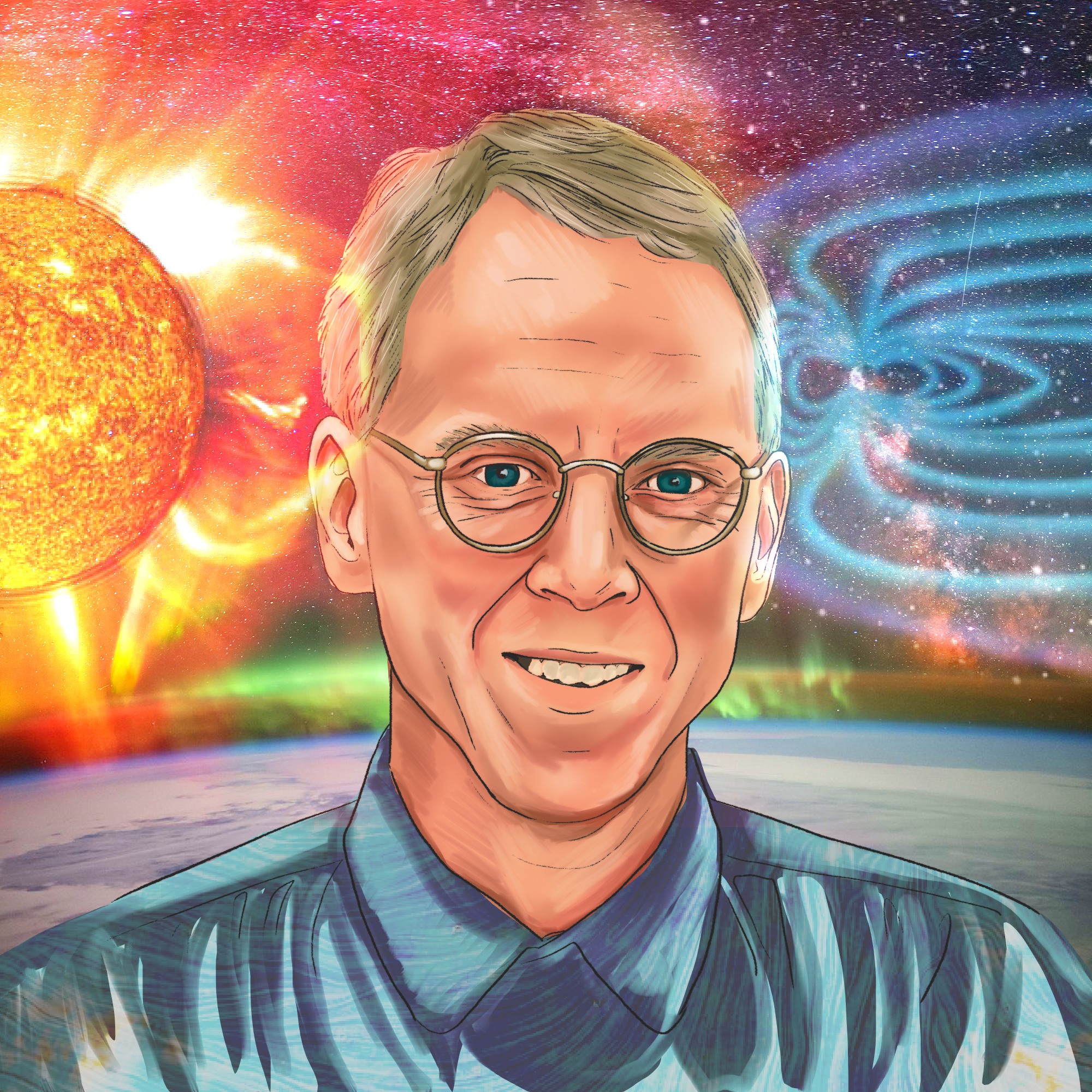

With a heliophysics career spanning across nearly five decades, Thomas Earle Moore has always been fascinated by the Sun’s relationship with the Earth and how that relationship affects life on our planet. The impacts of space weather can be super noticeable when it results in brilliant auroras or large radiation storms that send astronauts scrambling for cover. But Thom also advocates for studies of longer-timescale phenomena, many of which are poorly understood. For example, Earth’s magnetic field periodically reverses, but no one knows exactly how or why, or when the next reversal will be, or what consequences might ensue when it does. Now that some of these studies are finally getting funded, Thom hopes the next generation of heliophysicists will take up the mantle (maybe literally?) and explore Earth’s long-term future.

With a heliophysics career spanning across nearly five decades, Thomas Earle Moore has always been fascinated by the Sun’s relationship with the Earth and how that relationship affects life on our planet. The impacts of space weather can be super noticeable when it results in brilliant auroras or large radiation storms that send astronauts scrambling for cover. But Thom also advocates for studies of longer-timescale phenomena, many of which are poorly understood. For example, Earth’s magnetic field periodically reverses, but no one knows exactly how or why, or when the next reversal will be, or what consequences might ensue when it does. Now that some of these studies are finally getting funded, Thom hopes the next generation of heliophysicists will take up the mantle (maybe literally?) and explore Earth’s long-term future.

This episode was produced by Katrina Jackson and mixed by Collin Warren. Illustration by Jace Steiner

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:00 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:03 Today we’re going to be talking about-

Vicky Thompson: 00:06 Wait. I have a question for you.

Shane Hanlon: 00:09 Okay.

Vicky Thompson: 00:09 I have a question for you today.

Shane Hanlon: 00:10 All right.

Vicky Thompson: 00:11 Have you ever been in a long distance relationship?

Shane Hanlon: 00:15 Goodness. Vicky, it is too early.

Vicky Thompson: 00:19 No. Never.

Shane Hanlon: 00:19 It’s always too early to talk about this. I have actually. I was in three long term, long distance relationships.

Vicky Thompson: 00:28 Three? Long term?

Shane Hanlon: 00:30 More than at least a couple years each.

Vicky Thompson: 00:33 No. Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:34 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 00:36 You’re not that old. That’s a significant chunk of your dating life.

Shane Hanlon: 00:41 You don’t have to tell me. College into grad school. I ended up moving a significant distance away from college into grad school and I would say in all of these, distance wasn’t the factor, frankly. But it didn’t help. College into grad school, grad school every six months honestly, because we were both scientists and had field seasons where we had to travel. We basically spend six months together and six months apart and six months together and six months apart because unfortunately, that’s what happens in academia sometimes. That’s more of an indictment of the system, if I’m being honest.

Vicky Thompson: 01:23 Blame it on the system.

Shane Hanlon: 01:25 I’m going to blame it on the system. Then when I first actually moved to DC, between DC and Pennsylvania. Again, some people make it work, but for me, again, and it was never the distance, but it wasn’t right. Now I’m getting married actually in a month.

Vicky Thompson: 01:45 Congratulations.

Shane Hanlon: 01:46 I’m pretty happy the way things turned out with how things are going.

Vicky Thompson: 01:53 Yeah. Darn those other relationships.

Shane Hanlon: 01:55 Not super great on my end. What about you?

Vicky Thompson: 01:58 I’ve had a couple of long distance relationships and actually a couple of long distance periods with my husband now.

Shane Hanlon: 02:07 Oh really?

Vicky Thompson: 02:08 It all worked out. We always tried to think of it as military families are separated for long periods of time and they make it work. We can make work too. My husband and I met at science camp.

Shane Hanlon: 02:20 That’s so fitting for what we’re doing right now.

Vicky Thompson: 02:23 When we were in high school. We obviously were like, “Oh, we’re going to get married. We’ve known each other for three days and we’re going to get married.” Then we were immediately long distance, because we’re from different states and that did not work. But then we went to the same college.

Shane Hanlon: 02:38 Intentionally?

Vicky Thompson: 02:39 The science camp was at the college, and I’m lazy, I was like, “That’ll work.” I went to college there. It was a really good college, Hobart and William Smith.

Shane Hanlon: 02:48 There you go.

Vicky Thompson: 02:49 I think my husband researched more and ended up there legitimately. Then we dated on and off, did summers long distance. Then he moved to Vermont to do law school, we were long distance. Then I moved up after him. After we got married, actually, did a year apart.

Shane Hanlon: 03:08 Wow.

Vicky Thompson: 03:09 He found his dream job and he really wanted it. I said, “You could do that, but I don’t want to live where it is.” He moved away for a year and then moved back. We ended up in DC as a result of that.

Shane Hanlon: 03:22 Good for you all.

Vicky Thompson: 03:22 We made it work.

Shane Hanlon: 03:22 Look at that.

Vicky Thompson: 03:26 We got a lot of airline miles.

Shane Hanlon: 03:28 You know what, if nothing else, you got a lot of airline miles.

Vicky Thompson: 03:33 We’re just really independent people. It worked for us.

Shane Hanlon: 03:36 Good. I’m happy that this could end on a high note, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 03:39 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 03:45 Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists, for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 03:56 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 03:56 This is Third Pod from the Sun. Okay. We don’t need to belabor anymore of my unsuccessful experience with long distance. Vicky, your successful, good for you, experience with it. How all this fits into what we’re actually talking about today? We’re going to figure this all out and the better to explain where we’re actually going with this. I want to bring in producer Katrina Jackson. Hi, Katrina.

Katrina Jackson: 04:29 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 04:30 Why are we doing this? Why did we subject ourselves to talking about long distance relationships?

Katrina Jackson: 04:36 I thought this would be a good setup to talk about the long distance relationship that we all have with that giant ball of plasma 90 million miles away.

Vicky Thompson: 04:45 You’re talking about the sun? That’s a good setup. Are you setting us up with the sun?

Katrina Jackson: 04:50 You’ve already been pretty much dating the sun your whole life. Wait. Maybe that analogy is getting a little weird.

Shane Hanlon: 04:57 We’ve been in a relationship with the sun. That’s okay, but just a physical one. That’s weird too.

Vicky Thompson: 05:06 A relationship based on physics.

Shane Hanlon: 05:09 A physics soul relationship?

Vicky Thompson: 05:12 Stop.

Shane Hanlon: 05:14 Never. Brings me so much joy. Okay, back on track. We are talking about stuff like, what? How hot it is? Or the sun making plants grow? What are we talking about with this relationship?

Katrina Jackson: 05:31 This is more the relationship between the sun and earth and space weather, that sort of relationship.

Shane Hanlon: 05:38 I see. Okay. You leave it to Katrina to bring things back to actually being relevant.

Vicky Thompson: 05:44 Back to science.

Katrina Jackson: 05:47 For this episode, I talked with Thomas Moore, who has had an extensive career in heliophysics for more than four decades. Heliophysics, as the name implies, is physics of the sun. The solar atmosphere actually extends throughout the whole solar system. It’s also the study of how the gases and plasmas from the sun interact with each of the planets, including earth. I asked Tom about his career in heliophysics and what he would like to see happen in this field in the future.

Shane Hanlon: 06:15 Great. Let’s get into it.

Thomas Earle Mo…: 06:27 I’m Thomas Earle Moore. I’m a heliophysicist. And also maybe with a subspecialty in geospace physics, which makes me a geophysicist, which allows me to be a member of the American Geophysical Union.

Katrina Jackson: 06:41 Throughout your career you’ve been mostly interested in studying our own solar system compared to other solar systems. Is that correct?

Thomas Earle Mo…: 06:48 Yeah, when I headed for graduate school, I had thought about did I want to go into astrophysics or something different. I was specifically looking to study this kind of subject inside the solar system and mainly because we are here. People and life is only known so far to be inside our solar system and really only on our planet. I had this underlying interest in life and evolution, I guess. Not so much in biology, although you can’t really separate them. Anyhow, that was the discriminator for me. Heliophysics, everything inside the solar system, then there’s all the stuff outside the solar system, which gotten to be more and more interesting over time.

Katrina Jackson: 07:40 I hear you got to do sounding rocket experiments in grad school to study the auroras. What was that like? Did you get to go to any interesting places to do that?

Thomas Earle Mo…: 07:50 Yeah. They were mostly arctic places and they were very interesting. My graduate project was done out of Alaska, Chatanika, which is near Fairbanks. You’re way up in the Arctic Circle and the aurora comes out there almost every night or at least every few nights. You can do a two-week or three-week expedition or field expedition up there. I think the best aurora I ever saw though was in Tanglewood, the Tanglewood Music Theater in, I think it’s Lenox, Massachusetts, where aurora came out during a Rachmaninoff performance. It was like it was choreographed. It was just unbelievably gorgeous aurora in Western Massachusetts. Nice and dark out there with a symphony playing. Fantastic.

Katrina Jackson: 08:46 I assume that wasn’t part of any of your rockets experiments, that was just you were at a concert?

Thomas Earle Mo…: 08:52 No, that was just good karma. I did see aurora in Huntsville, Alabama once.

Katrina Jackson: 08:57 Really?

Thomas Earle Mo…: 08:58 Barn burning red aurora. Yeah, it’s very unusual. The biggest space storms that occur can send the aurora down that far and even to Florida, very rarely. A buddy of mine rousted me out to see it.

Shane Hanlon: 09:22 Question for the two of you. Have you all ever seen an aurora, the Arctic Aurora? I haven’t unfortunately. I would love to, but haven’t been fortunate enough to.

Vicky Thompson: 09:34 I haven’t either.

Katrina Jackson: 09:35 I have actually. Back when I was in grad school in North Dakota, I was able to see a little bit of the aurora there and up into the border with Canada. I’ve also in Arctic, Sweden, I’ve seen the aurora there. I’ve never seen a really big colorful aurora with all the different colors, the greens and the reds and the purple. I’ve only seen a little bit of the green. It would be cool to see a really big good one.

Shane Hanlon: 09:58 I can understand wanting to. I just want to see something full stop. I assume, I think the farthest north I’ve ever been is in parts of Iceland. I figure we’re too far south here, obviously, to see anything like that.

Katrina Jackson: 10:13 Apparently if there’s a really big storm, you might be able to see it as far as south as here. Tom mentioned seeing that one all the way down in Alabama. You’ve got to have a really big storm for it to be visible way down there.

Shane Hanlon: 10:24 I don’t know what’s the return on investment or what makes it worth it to have a storm that big enough? I think I’d be worried about other things happening other than just seeing an aurora.

Katrina Jackson: 10:35 Tom was actually telling me about a really big solar storm that happened in 1972. I think you talked about that storm on this podcast a few years ago. About how it caused sea mines near North Vietnam to explode.

Shane Hanlon: 10:48 Yeah. That was such a wild story. That was in the fledgling days of Third Pod. But go back and listen to it, folks. We’ll put a link to it in the notes, but the cliff notes is there. It was a solar storm that ended up causing naval mines, think aquatic mines that sink things like Battleship, “You’ve sunk my battleship,” to explode. Or at least that’s the running hypothesis.

Katrina Jackson: 11:13 A big solar storm like that can cause all these kinds of weird effects on earth. But generally our atmosphere and our magnetic field protects us from the worst of it. If you’re out in space, and remember what was happening in the space program in the early 1970s.

Vicky Thompson: 11:27 The Apollo missions.

Katrina Jackson: 11:29 Right. Apollo 16 was in April 1972, Apollo 17 was in December, and this solar storm happened in August. Luckily, astronauts were not out there during the storm.

Shane Hanlon: 11:42 Then that’s great, but what if they had been?

Katrina Jackson: 11:46 What would’ve happened if astronauts were out there on one of the Apollo missions during that storm?

Thomas Earle Mo…: 11:53 They would’ve been sickened by radiation from the energetic particle fluxes from the part of the storm is tremendous fluxes of energetic particles that basically like sitting near a radioactive source, getting too close to a radioactive source, except you’re bathed in them. You’d be out there relatively unshielded by anything. The space vehicles aren’t a lot of shielding. You’re exposed for hours and you could very easily be so sickened that they might never have made it, been able to manage to make the trip back.

Katrina Jackson: 12:30 I was going to ask is that something you would’ve noticed, they would’ve noticed right away? Or is it something that they wouldn’t have noticed until later? But sounds like pretty quickly.

Thomas Earle Mo…: 12:38 It comes on pretty quickly if it’s that intense, within hours or a few hours. I would say maybe even quicker than that, depending on the exposure level. Anyway, it was a potentially lethal dose that would’ve been experienced by astronauts had they been there at the wrong time.

Katrina Jackson: 12:58 I imagine our ability to forecast space weather’s gotten better over the years. Would they have been able to know that storm was coming, back in 1972?

Thomas Earle Mo…: 13:07 No. The sun is pretty unpredictable. You can follow what it’s doing when it starts having a solar flare or solar mass ejection. The result is sometimes expressed as a billion tons of matter going a million miles an hour away from the sun, and sometimes that’s toward the earth, a luck of the roulette wheel where the earth happens to be at the moment that occurs or few days after that occurs. Takes a few days for it to reach the earth.

Katrina Jackson: 13:42 Would we have any better forecasting for the Artemis missions coming up for anyone going to the moon in the next few years if one of these storms came?

Thomas Earle Mo…: 13:55 Yes, and there’ll be warnings. I think they’ll probably go with mechanisms to shield themselves. They’ll set up ways of being shielded and scramming into a shielded structure if the storm is found to be approaching. Actually, I don’t know if you watched the streaming show, For All Mankind, they did a nice, in some ways, nice dramatization of what would happen on the moon if there were a base up there, a colony of astronauts and one of those storms occurred.

Thomas Earle Mo…: 14:34 Of course people were out and about and needed to scram into caves or back to the home base structure in order to get out of the storm. There were other reasons why certain people couldn’t quite do that and other people got stuck on the surface of the moon. Other people tried to save them. It was really quite a nice dramatization of the kind of things that can happen. Anybody that goes there in the future, I’m sure will be prepared to try and duck such radiation levels and stay safe and they’ll have good support. There’ll be known hours in advance that something is coming.

Shane Hanlon: 15:19 I really love this mention of For All Mankind. We are not sponsored by, have any affiliation with the show, but I personally really enjoyed this show. Have either of you watched it?

Vicky Thompson: 15:30 I haven’t.

Katrina Jackson: 15:31 I hadn’t watched any of it until I did this interview and then I was curious about this episode. I went and watched it. This is the first episode of season two, I didn’t really know who the characters were, but after I watched it, then I went back and started from season one and now I’m almost finished with season two.

Vicky Thompson: 15:48 Binge.

Shane Hanlon: 15:50 We’re not giving anything away, but it’s basically what if the space race never stopped essentially, this alternative history. And it does raise some interesting questions, not just about space per se, but about what happens if you get stranded somewhere and you can’t get back? Things about how the political system works from a space perspective and, I’m a nerd, from a nerd perspective, I really enjoy it.

Vicky Thompson: 16:14 Speaking of getting stranded in space and also the politics of that, has anyone seen Light year, the new Buzz Lightyear movie? That’s more my speed.

Katrina Jackson: 16:23 I haven’t. No.

Shane Hanlon: 16:24 I have seen Lightyear. You know what? I feel the folks are giving Lightyear a hard time. I really enjoyed it. It’s a fun romp and it’s a Pixar movie, it tackles some serious stuff.

Vicky Thompson: 16:37 Yeah, I feel like maybe… I haven’t seen For All Mankind, but it sounds like it’s tackling some of the same issues.

Shane Hanlon: 16:46 Who would’ve thought people would be listening to… I listened to a lot of pop culture podcasts as well, who would’ve thought that we’d have a mix of pop culture and sciencey stuff on Third Pod, but we are more squarely in the sciencey realm and storytelling. I’m going to be the responsible one here and get us back on track by now deferring back to Katrina to actually get us truly back on track.

Katrina Jackson: 17:10 That episode in For All Mankind was about the solar storm happening on the moon, and it was an interesting depiction of it, but it can really show why space weather is an important thing to study in Heliophysics. We want to be able to understand really well what can happen in these events, and we want to be able to accurately forecast these events. But on the other hand, Tom was telling me that personally he’s actually interested in some of the aspects of heliophysics that take place over longer time scales.

Thomas Earle Mo…: 17:35 I’ve become an advocate in my retirement for worrying about longer term things. There’s many, many, many fast timescale processes that we’ve been studying for some time, and all of them are very interesting in becoming better and better known. But I’m an advocate that we need to look into the future as far as we can. That’s really what distinguishes human beings is having the ability to anticipate, really speculate, but preferably actually anticipate what kinds of things will happen.

Thomas Earle Mo…: 18:10 Once you understand what’s going on, you can anticipate where it’s going. And I’m an advocate for doing as much advanced thinking as we can and asking what will be the consequences of something like a geomagnetic field reversal? Our magnetic field flips, reduces near zero and then becomes strong in the opposite direction every about four or five times per million years. This is a long time scale. The sun itself, of course, has magnetic cycle. That’s 11 years long that I mentioned earlier. And that’s important. And you can actually run a space mission that will last 11 years and witness what goes on over a decade in space. We’ve learned heck of a lot about what that process is and how it works.

Katrina Jackson: 19:06 Going back to the geomagnetic field reversal, when was the last time that happened? How long does it take for that to happen? What would be some effects of that happening?

Thomas Earle Mo…: 19:17 It’s fairly random, but the average over eons is about five times per million years, so 200,000 years, but it’s been 750,000 years since there was a real good solid reversal. Although, about 40,000 years ago, there was almost a reversal. Where the magnetic field got much weaker and gave some evidence of… It’s hard to envision what this dynamo is that makes the magnetic field, although we study that. There are people who are studying that very carefully.

Thomas Earle Mo…: 19:55 It’s an irregular, somewhat chaotic process apparently that is isn’t periodic. It’s not nice. Every 11 years the sun, by contrast, is pretty regular with it’s 11 year cycle. Although, it does hiccup at times and stop the cycle and then restart it. Where am I going here with this? The thing with the geomagnetic reversals is that we should be able to understand quite well what would happen to our magnetosphere? What would happen to our interaction with the sun? What the aurora would do during a geomagnetic reversal? And we may have one starting up now, but it’ll take a couple thousand years to play out. When you try to propose studying these kinds of things, you get a bit of pushback that it’s hard to envision a NASA mission that would study a thousand year long process. You can study a 10 year long process pretty conveniently, but you have to come from different angles than the standard way of doing business.

Shane Hanlon: 21:09 I don’t think, I know I don’t, fully understand this geomagnetic reversal thing.

Vicky Thompson: 21:16 Basically the North Pole becomes the South Pole and the South Pole becomes the North Pole?

Katrina Jackson: 21:21 Yeah, that’s the gist. But I don’t think anyone really fully understands it. At least that’s the impression I got from my conversation with Tom and the little bit of reading I did. We can tell from rocks, when in the past these magnetic field reversals have happened and the frequency has been super variable. At some points, the geomagnetic field stayed the same for tens of millions of years, and at some points the field was flipping back and forth over just tens of thousands of years. We know that much. But as for what causes it, when the next reversal will be and what exactly the effects will be when that field gets reversed, I don’t think anyone really knows.

Vicky Thompson: 21:59 That’s a really big mystery to solve yet.

Shane Hanlon: 22:02 I can see why Tom would be interested in these types of longer scale phenomenon. It sounds like there’s a lot left to study.

Vicky Thompson: 22:11 But how would you even go about studying that?

Katrina Jackson: 22:14 Have you had any pushback to any of these ideas or wanting to study these longer time scale periods?

Thomas Earle Mo…: 22:22 Yeah, I have a few proposals that never were funded in which I had tried to propose some contributions to that. They were basically found to be outside the mainstream of concerns in heliophysics or not possible to address with a 10 year long space mission. We need different ways of coming at that problem than 10 year long space missions, clearly. I ended up somewhat frustrated by those efforts and maybe this is an expression of that frustration that I think we really do need to worry about that somehow. I’m really encouraged that NASA has funded the study of what the effect of magnetic fields are on planet atmospheres, whether they help the solar wind to scour the atmosphere off the planet or protect the atmosphere from that scouring. Really encouraged to see that happening. And I think that’s a step in the right direction.

Katrina Jackson: 23:32 And what else would you like to see in terms of trying to study these longer time scales? Like you said, a 10 year mission’s probably not going to cut it. Are you wanting a mission that lasts longer or are there other ways to try to approach the problem?

Thomas Earle Mo…: 23:47 I think one fairly obvious thing is to take the theories that we have that we think are pretty good theories and simulations that we feel are pretty good on time scales that we’ve worried about so far, and test how they test them on longer time scales. I think that’s the immediate thing that could be going on is the simulation groups could be testing their models and ask. Testing them in ranges where they don’t normally test them. That will help to make the models stronger, I think and more accurate.

Thomas Earle Mo…: 24:21 As far as actually observing things, the geomagnetic observations are interesting. Those come from the upwelling of the crust on the ocean floor and the spreading across the ocean floor. And you see a record across the ocean floor of different magnetic orientations for these that correspond to the various reversals of our field. Beautiful result, geology result. Can’t really do that with a space mission, but I think we need to think up new ways of observing this long term history. And I’m not sure what they are. I’m waving the flag that it would be important if anybody could figure out how to do that.

Katrina Jackson: 25:05 And you talked in your paper about humans wanting something bigger than ourselves to outlive us. What impact on science or on the human story do you hope to leave behind?

Thomas Earle Mo…: 25:20 I’m pretty pleased with the idea that some of these studies are getting funded now, and I contributed to proposing them and I’m glad to see them getting funded. And I think the younger generation is going to carry that stuff on and it’s an elating thing, relation to see that they’re succeeding.

Katrina Jackson: 25:51 That’s a pretty big question, but I’ll ask you the same question I asked Tom. What impact do you want to leave behind?

Shane Hanlon: 25:58 This podcast.

Vicky Thompson: 26:03 I want to be buried with a copy of this podcast.

Shane Hanlon: 26:07 It’ll be a much smaller, very more personal version of Carl Sagan at all being on Voyager way out in the Galaxy, except I’ll be… I actually don’t know if I think I want to be buried. I probably want to be cremated, we’ll just put it… I know we’re getting into some stuff here.

Vicky Thompson: 26:24 We’re really getting deep here.

Shane Hanlon: 26:25 But whatever the form of audio is, however you save audio, hopefully many years from now, we’ll just set that beside the urn.

Vicky Thompson: 26:33 I just had a terrible thought of somebody coming along and dumping out your ashes and this 8-track tape falls out.

Shane Hanlon: 26:39 Why is it an 8-track?

Vicky Thompson: 26:44 In the future that would be the equivalent.

Shane Hanlon: 26:47 I’m not that old Vicky, like my generation was probably CD’s.

Vicky Thompson: 26:51 Equivalent of an 8-track.

Shane Hanlon: 26:53 All right, with that lovely imagery that is all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 27:00 Thanks so much Katrina, for bringing us this story and to Tom for sharing his work with us.

Shane Hanlon: 27:05 This episode was produced by Katrina, with audio engineering from Collin Warren, artwork by Jace Steiner.

Vicky Thompson: 27:11 We’d love to hear your thoughts on the podcast. Please rate and review us and you can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 27:20 Thanks all, and we’ll see you next week.

Shane Hanlon: 27:26 Is this your ASMR?.

Vicky Thompson: 27:26 This again, ASMR. I just put my ear up to the microphone. Like I could hear it better.

Shane Hanlon: 27:36 That’s actually worse because then you would get the feedback that Katrina was having. It would come out of the mic or come out of your ears, go into the mic, come out of your ears, go to the mic.

Vicky Thompson: 27:44 When I was little, my mom, she’d be driving and if she had to reverse into a spot, a parking spot or really concentrate if there’s a tricky situation, she would turn the radio off and she would yell at us to stop talking because she would need silence.

Shane Hanlon: 28:03 Just need to concentrate.

Vicky Thompson: 28:03 She would always say, “I can’t see, be quiet.” I feel like somehow me putting my ear to the microphone to hear better is related.

Shane Hanlon: 28:14 I love that.