21 November 2014

Thinking of giving a TEDx-style talk? Do it – but with plenty of preparation!

Posted by Olivia Ambrogio

By Jenny Fisher

Jenny Fisher, a postdoc at the University of Wollongong, explains during a Budding Ideas forum how atmospheric computer models can be used to show where pollution comes from. The forum was organized by the University of Wollongong Research Office with the goal of sharing the work of early career researchers with the local community. Photo by University of Wollongong Research.

Although presenting my research to scientific audiences has always been one of my favorite parts of being a scientist, I’ve never found the opportunity or the courage to share my work more publicly. But that changed last March when an email popped up in my inbox from the research office at the University of Wollongong (UOW), where I am researching atmospheric chemistry. The email was a request for early career researchers to share their research ideas with the public at a new event called Budding Ideas. After a few days of internal debate— followed by a few months of intense preparation— I found myself for the first time on a public stage.

Budding Ideas is a new research showcase developed by UOW’s research promotions unit. Modeled after TEDx, the goal of the event is to share the brilliance of UOW’s early career researchers with the public during an evening of 10-minute, image-driven, easy to understand talks. When I first received the invite, I hemmed and hawed about whether to apply. On one hand, I liked the idea of finally presenting to a public audience. On the other hand, I didn’t feel like I had brilliant ideas of my own to share. Instead, I wanted to convey the community nature of the scientific process, as represented by atmospheric models. At the last minute I submitted this idea, and the organizing committee went for it.

Preparing for the talk was hard work, mostly enforced by the event organizers, but well worth it. When I signed up, the two months’ prep time seemed long, but they passed quickly. In the last week, I started nearly every morning with a round of practicing my talk aloud while staring out the kitchen window (luckily only a few passersby looked back in!). In the end, the talk was a success – I felt confident, the audience was interested, and I even got asked a question by the Vice Chancellor (the university’s head honcho).

The prep work made all the difference, and much of my preparation would be more broadly applicable. Here are my five tips for anyone preparing to do a short public talk, TEDx or otherwise:

1. Start early!

I’m usually organized, but this was a stretch even for me. We had a video-taped rehearsal a month before the event, at which point it became clear just how much work we all needed to do. After the rehearsal, I focused on timing – using key pauses to hit the most important messages.

2. Get inspiration, but not too much.

I started by watching a lot of TED talks. This was fun, and it gave me ideas about ways to convey complex topics. When the possibilities began to seem more overwhelming than inspiring, I stopped watching and started writing.

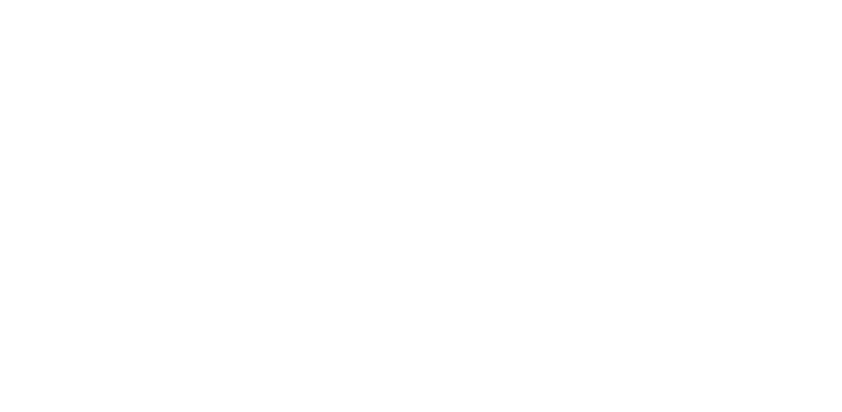

A graphical representation of the way atmospheric models can be used to “fill in the gaps” left by sparse measurement networks. The circles represent locations in Australia where atmospheric pollutants are measured, and the colored background shows model-predicted pollution over the whole region. Graphic by Jenny Fisher, University of Wollongong.

3. Find / make / commission great images.

With limited time, images become central to the narrative. I was really lucky to have access to graphic designers who turned my mental images into beautiful, concrete ones. Side note: make sure you’re happy with the final product since it will ultimately be associated with you!

4. Practice, practice, practice.

This goes without saying, especially when the talk is so short. In the end I memorized it – something I had never done before. It worked well and guaranteed that the main messages were phrased in the most powerful way possible.

And, of course…

5. Enjoy the experience.

I did! I got to meet so many people– the other speakers, the media, public relations teams, administrators, and researchers from other faculties. Thanks to the graphic designers, I got fantastic images to use again and again in my talks. Because the event was live-streamed and recorded, I ended up with a YouTube video to share my work with friends and family around the world. And most importantly, I finally got an opportunity to help make people more informed about science.

So, if you see a similar request land in your inbox, I highly recommend you go for it.

– Jenny Fisher is a Vice Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Wollongong conducting research on the sources, transport and chemistry of air pollution in the Southern Hemisphere. Her work combines observations datasets with atmospheric models to extract the most information from both.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.