21 September 2016

Sikuliaq week 2 recap

Posted by larryohanlon

This is the latest in a series of dispatches from scientists and education officers aboard the National Science Foundation’s R/V Sikuliaq. Read more posts here. Track the Sikuliaq’s progress here.

By Kim Kenny

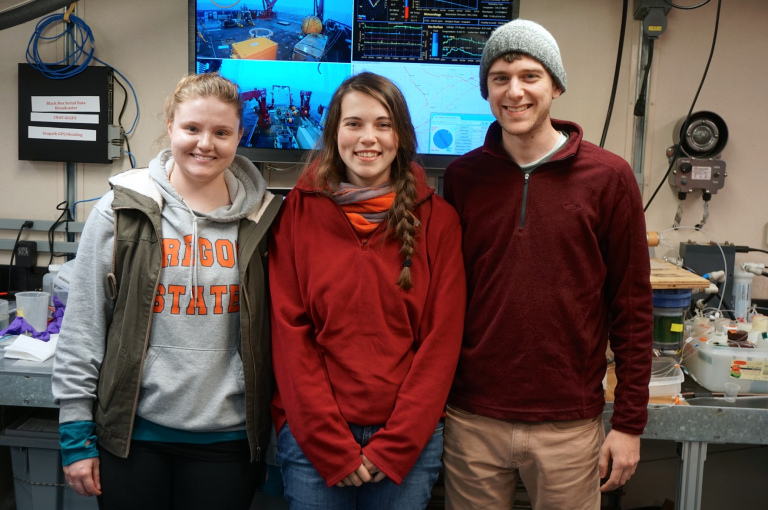

We’ve done a lot of science this week! Since the last update, we’ve successfully towed the super sucker, started multi-coring, and upped our CTD tally to a whopping 87 casts, plus all the continuous surface underway data we’ve collected while steaming between sites. The scientists have some preliminary results and ideas about where they’d like to visit again (the beginning of the Wainwright line is of particular interest).

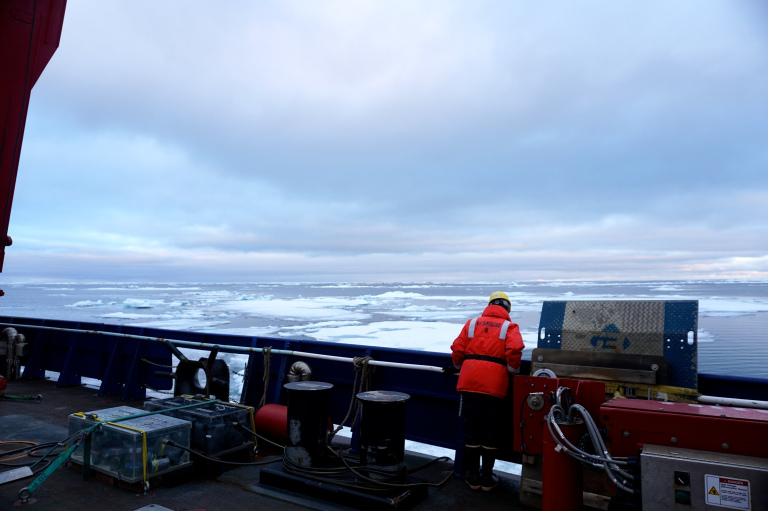

We’ve navigated through a surprising amount of ice. The days have continued to blur into a forever fluctuating schedule of sampling shifts. There were a couple stressful decision points and frustrated interactions. Our ship community of scientists and crew feels closer, bonding over shared goals in the face of sleep deprivation.

After two weeks, I’m surprised by how engulfed I am in life here. My reality is a wall of colorful display screens, sticky mats that keep gear from sliding, snippets of radio chatter, two forever-filled mess hall pots of coffee, puffy orange jackets on yellow hangers, the soul-sucking whoosh of flushing the head, the lounge table’s smooth wood, a steep stairway, the long whine of the engineering alarm, the voices and mannerisms of the people I see every day. I wake up wanting to know what science and operations I missed during the hours I slept. I know that somewhere out in the real world, a presidential race is happening, friends and family have their dramas, that in two weeks I’ll return to that world and care deeply about it. But right now the most imminent science op feels more important.

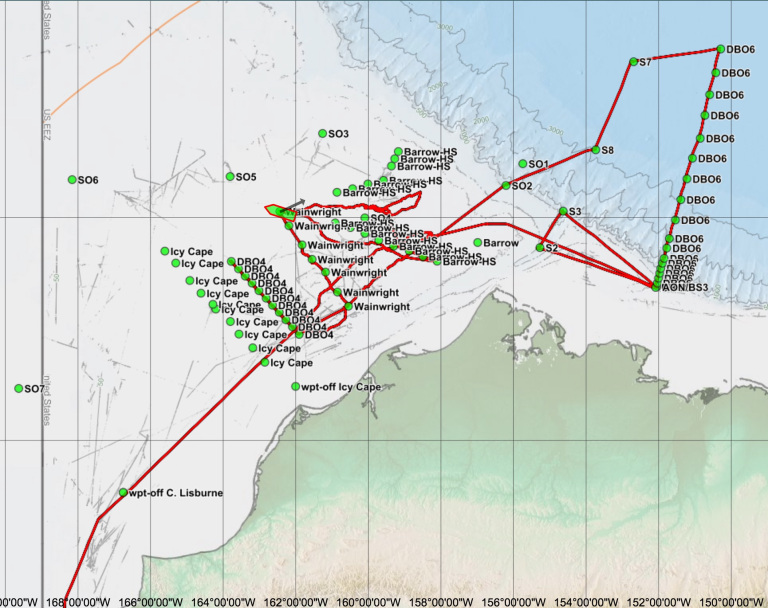

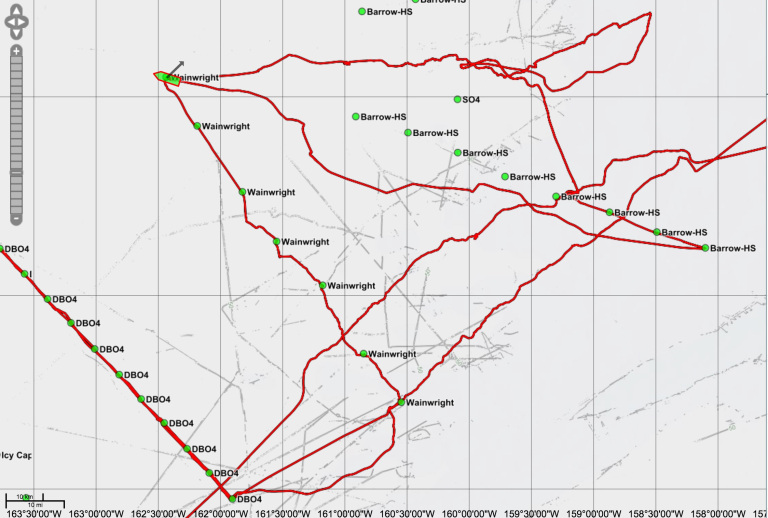

At the end of last week, we were headed past the ice toward the DBO 4 line. Since then, we’ve towed the super sucker up DBO 4 on the Chukchi Shelf. Then we did 11 CTDs on the way back down DBO 4. From there we steamed east back to the Wainwright line because the ice coverage had lessened enough for us to get there. We did 7 CTDs and 4 multi-cores on the way up the Wainwright line.

At the end of the Wainwright line on Wednesday, we reached a turning point – the super sucker wasn’t working, and we wanted to get to the “top” of the Barrow/Hannah Shoal (BHS) line to the east but there was too much ice. So an impromptu meeting happened in the computer room, and it was decided we’d have a night of transit down to the “bottom” of BHS. Operating a ship like this costs about $50,000 per day ($40 per minute), so when things don’t go according to plan, it can stressful. Everyone wants to get the most out of every day. But the equipment wasn’t ready, we couldn’t get to where we wanted to go, and most people really needed the sleep, so the plan changed – we navigated southeast through the ice to the bottom of BHS. That was a striking night for me to witness – the scientists coming to terms with what they can and can’t do, and working together to brainstorm the best path forward.

Ops resumed on BHS Thursday morning. Four CTDs and four multi-cores later, the ice stopped us in our tracks again. So we moved away from the BHS, parallel to the ice pack, and deployed the super sucker. The ice prevented us from getting as far north as we wanted – to the BHS north line – so we “made up” a new line as close to BHS north as we could get, and did 6 CTDs and 4 multi-cores. There was a long transit in-between each station because of the ice and that made for long work hours.

At the top of the Wainwright line, we deployed the super sucker for 24hrs, which gave most people a chance to sleep. By Sunday afternoon – when this post was written – we were at the “bottom” of the Wainwright line, closest to shore. Here we “stopped” and began a 24hr series of CTDs, about one CTD every hour. After this CTD marathon, the plan is to reevaluate the ice conditions and likely go to DBO 4.

From there we hope to hit the Icy Cape line, but we have to make sure to leave enough time to get back to Nome and account for weather.

It might be noted that the recounting of the events of the last week had to be corroborated by five different sources. Even the people participating had a hard time remembering exactly what happened the past week – everything blurs together and we just focus on getting the job at hand done.

We experienced rolling on the ship for first time this weekend. There was enough of a swell for small objects to fall off tables, for water to be the almost complete view out the porthole, for you to lose your balance if you’re not paying attention. We were “in the trough,” meaning the ship was steaming parallel to the waves. The sweet spot, I’m told, is when the ship is steaming head-on into the waves – this reduces the roll.

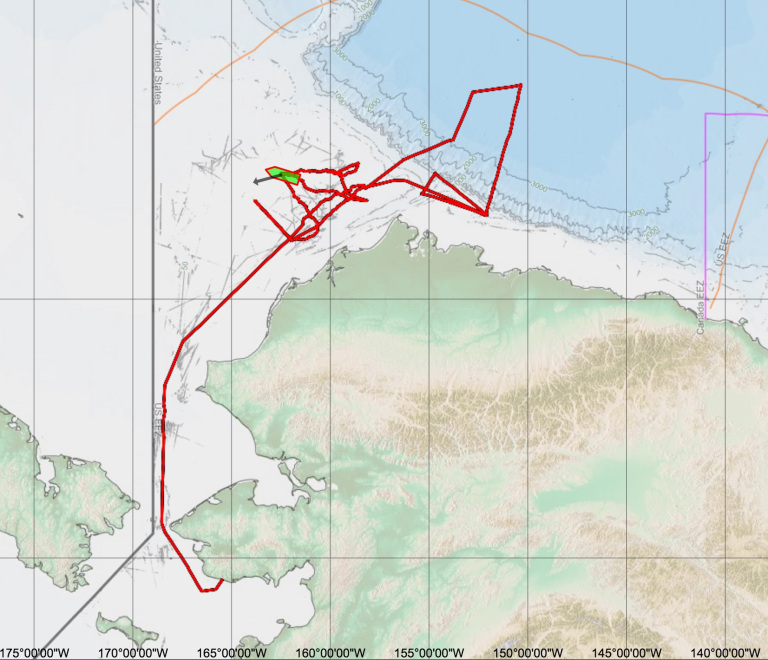

Here’s where we’ve been in the past two weeks:

Screenshots from the map server on the Sikuliaq. The orange lines denote U.S. Exclusive Economic Zones and the pink lines denote Canadian Exclusive EZs. Note the slight overlap. The black line shows the border with Russia.

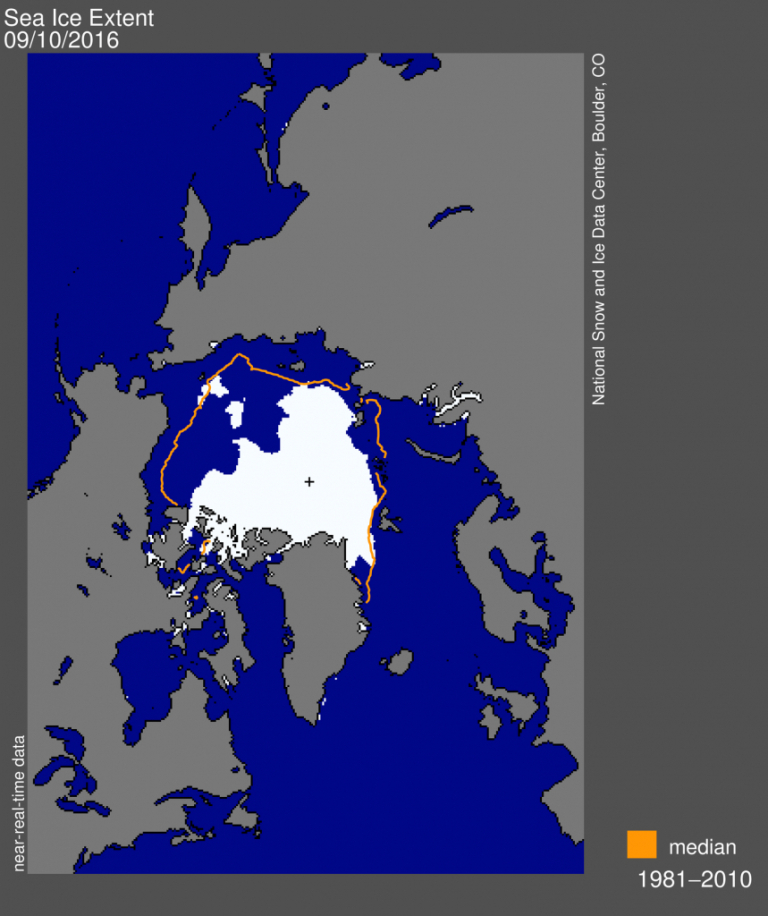

SEA ICE MINIMUM

Arctic ice cover hit its minimum for the year last Saturday. The announcement came on Wednesday from the National Snow and Ice Data Center. It’s a milestone – usually in mid-September – that the Arctic community is very aware of. I was struck by this awareness when some of the crew talked about it on the bridge, with the same familiarity those of us in the lower 48 (what Alaskans call people who live south of the 48th parallel) might have discussing the coming of…the summer solstice? New Years? It’s not on the same day every year and it’s not looked forward to as much as kept in mind. Maybe like the annual family Thanksgiving feud – you know it’s coming, it’s generally around the same time every year, you’re not exactly sure which day, but you’d say to your cousin before carving the turkey, “About that time, eh?” The ice minimum is an important marker in the year, the turn-around point after which the ice cover starts increasing.

The ice minimum defines scientific schedules. It defined the planning for this trip. This year tied for second lowest ice coverage with 2007 (2012 has the title for lowest ice coverage). “Low” is 1.6 million square miles (4.14 million square kilometers) of ice, measured by the satellite geniuses in Colorado who have been monitoring this for 37 years. This year is also special because the Arctic has lost ice at a faster rate than usual.

Arctic sea ice extent for September 10, 2016 was 4.14 million square kilometers (1.60 million square miles). The orange line shows the 1981 to 2010 median extent for that day. The black cross indicates the geographic North Pole. Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center.

Ironically – despite the low ice coverage in the Arctic as a whole – ice has continued to be a surprisingly prevalent part of our research cruise. And a bit of a pain for the research we want to do; the ice sits over many of our intended sample sites. Laurie jokingly called the theme for this week: “Wherever you want to go, that’s where ice will be.” September was “supposed” to be a low month for ice cover in the Chukchi Sea, but turns out nature doesn’t always act according to plan.

A lot of careful planning went into this trip, we’ve used all the latest technology, ice maps, and satellite images. But still the ice is constantly changing and it’s hard to know where it is or will be. Sometimes visual cues are best. The Inupiat people – native Alaskans most heavily congregated on the north slope of Alaska – have well-known, time-honored visual cues to navigate the ice. One of these is called “water sky,” essentially a view on the horizon of a patch of water just below open sky. If you aim for that, it’s often better than trying to navigate through the ice right in front of the ship or by watching the radar. The water we’ve been going through is very near the freezing point, so more ice could be “re-freezing” soon.

It may have caused inconveniences, but the ice has continued to be beautiful, and afforded us some incredible wildlife viewings. On Tuesday we got our closest glimpse of a pair of polar bears on the ice. I love watching them put their noses in the air, smelling us, and the placid gaze they direct our way as we pass. I’m guilty of anthropomorphizing, giving them deep dopey voices. Of course they’re powerful, dangerous creatures to be respected, but they do look cute from the safety of the bridge.

We saw about 500 walruses on Thursday, huddled in brown masses on the ice. Hearing them barking and grumbling was fantastic. That’s the most animated I’ve seen Herbert, the Inupiat community observer who spends most of his time in one of the raised chairs on the bridge, binoculars in hand. He’s usually extremely soft-spoken, so much so that you have to lean in and almost lip-read to know what he’s saying, but he raised his voice slightly on Thursday to say that was the most walruses he’s ever seen. The next day he brought a walrus tusk up onto the bridge that he’d found on a beach near Wainwright and carved “Alaska” into.

Definitely one of the best parts of the wildlife viewings have been seeing the genuine enthusiasm it inspires in people. It’s impossible for me not to feel pangs of joy seeing walruses, even if they do tend to hang out near piles of their own feces. My thoughts of walruses being cute have been dampened slightly after watching “Tusk” on Saturday night, in which Justin Long gets turned into a walrus by a serial killer. (Johnny Depp’s in it too. Actually a pretty fun movie. Slightly better than Sharknado.)

On Saturday we saw two polar bears swimming off the starboard bow, far from ice. It was a good spot by captain Adam Seamans, and chief mate Diego Mello said that was a rare sight. Polar bears can swim for a while, but still these two seemed pretty stranded.

A few favorite moments

There are so many little moments in the day that can feel like they slip through the cracks of recollection, but seem to contain so much of what it’s like to be onboard, so I’m jotting down a few of those here.

Tuesday:

- Sitting in the computer room deploying the CTD at about 1am. Carrie, a graduate student in Burke’s lab, is “driving” the CTD and Artie, an AB crew member (“able-bodied”), is operating the winch from another room. They communicate via radio. We can always tell when it’s Artie on the radio because of his unrelenting enthusiasm. Artie is relatively new on the ship so his nickname is still in flux; one of the options is “whiskers” (he has a budding beard). Ethan, the handyman marine tech, tells Carrie to say, “Good morning, Whiskers!” which she does. Then Carrie is encouraged by Ethan and Miguel to out-friendly Artie, questionably an impossible task. So the next series of radio communications are obnoxiously and increasingly emphatic, as in “Pleeeease take the CTD to 10 meters!” and “Rooooggger that, taking the CTD to 10 meters!” On for the rest of the 30min cast. This seemed hilarious to us at the time.

- Miguel started saying “that’s dank.”

- The dinosaur no-internet game. You hit the up key when the internet isn’t working, and your view will turn into a conveyer belt of landscape, and you use the up key to have the dinosaur jump over obstacles. Laurie leaned over my shoulder for a good five minutes watching me play and we were both very entertained.

- Up late to help multi-core. I’ve only done this crazy schedule once, while Miguel has pulled all-nighters multiple times. Cold, blue-gloved hands as I helped cut 1cm slices of sediment from the core at 3am. Miguel’s hands must’ve been even colder since he was washing the dishes. Carrie and Kristi had thicker gloves but were cold too. No one complained and work was cheerful. Arty brought his phone out and we listened to “Living on a Prayer” and “Call Me Maybe.” Carrie and I did a little dance in our puffy orange coats and foul-weather overalls. The darkness around us seemed like four black sheets had been pulled over the sides of the ship. The air felt so still. The aft deck is abnormally flat, so the mud tends to pool and stay there. We try to lessen this by hosing off the deck after coring, and joke about how John French, an AB on this cruise and a seasoned bosun with a gray ponytail, won’t ever be satisfied with how clean it is. I go to bed at 7am and sleep until 3pm. I’m happy to realize I’m completely free to do this if I want — no one works a normal 9-5 job here.

Wednesday:

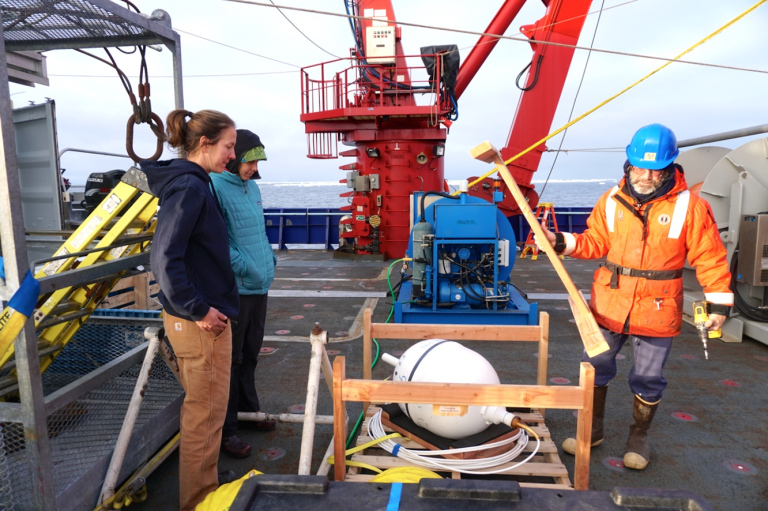

- A buoy deployment. One of Laurie’s colleagues at the University of Washington asked we deploy a buoy while we’re out here. This is normal for scientists to do – it’s hard to get out here and people want to take advantage of the opportunity even if they aren’t physically here.

- Talking. It’s just really nice to hang out between deployments and talk. About dogs, drawing, whales and whaling, books, other ships and cruises (the ship world and the oceanography world are both small), kids, hiking, future plans, food, music. There’s a lot of laughter on this ship – while just chatting and while working.

- Man overboard drill. This was mostly work for the crew, who put a heavy man-sized dummy overboard and launched a rescue vehicle to recover it. The rest of us hung out in the main lab and waited. After the drill, second mate John Hamill gave a brief presentation about hypothermia and Arctic safety in the mess hall.

Friday:

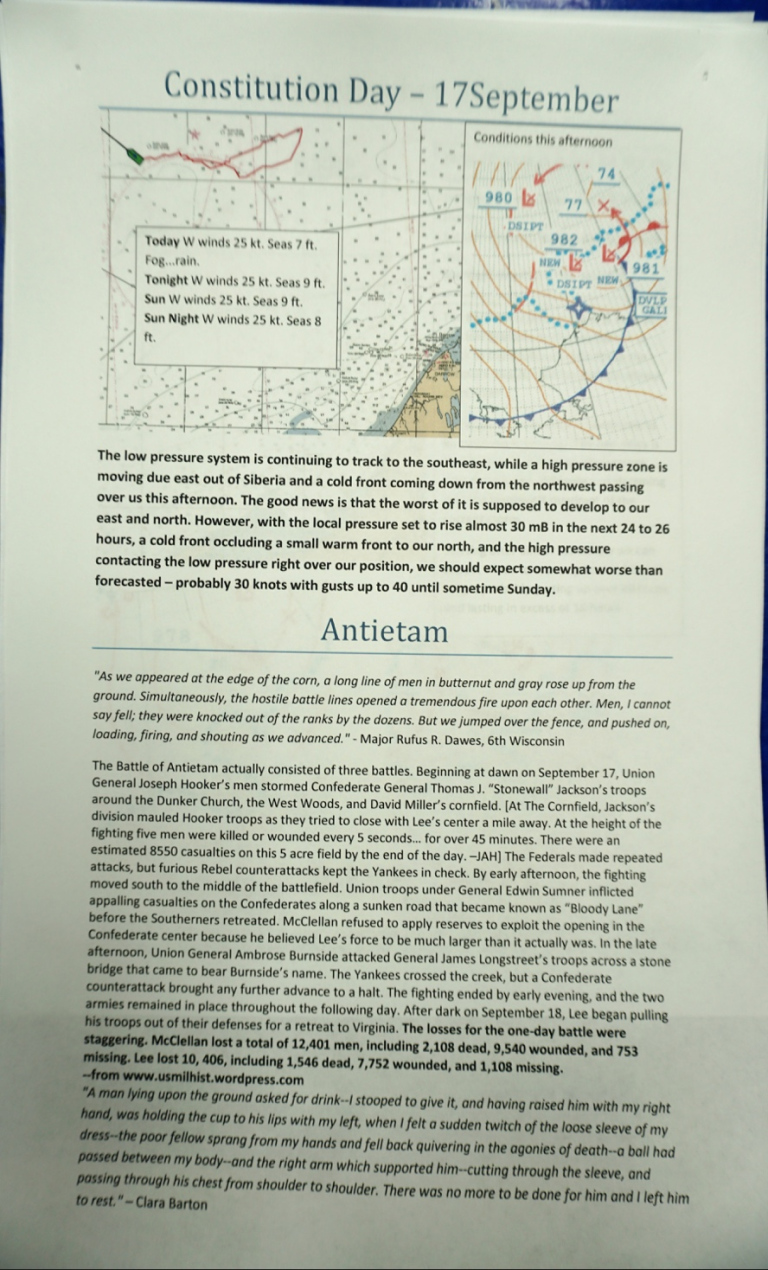

- Pounding through ice at night. The engineers joke that you can tell when John Hamill is driving, because we hit more ice. This isn’t because he’s unsafe – Hamill is the most safety-conscious person on the ship – but because he tends to take a more direct path through the ice. This ends up being safer and more efficient. From the gym, hitting the ice sounds loud and menacing, like feeling the pounding of a deep bass in your chest in the middle of a mosh pit. John Hamill has the shift that goes into the early morning, so he writes up the daily weather report for the next day, and posts that on the cork board in the mess hall. The reports include “On this day” snippets about the Revolutionary War, Civil War, or maritime history. September 17 included homage to Antietam.

Up next: video message to home from the science team and a closer look at the super sucker.

P.S. Kristi Okimoto is an intern on the ship working as a member of the crew through the Marine Advanced Technology Education (MATE) program. Check out her blog here!

— Kim Kenny is a freelance journalist who specializes in science writing and multimedia. This post was originally published on thedynamicarctic.wordpress.com

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.