27 April 2020

New Mexico badlands help researchers understand past Martian lava flows (video)

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

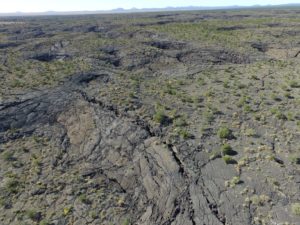

An aerial view of the McCartys flow field in western New Mexico, which is twice the size of Washington, D.C. Cracks in the rock show how the lava shrank as it cooled. Inflation pits can also be seen: pits that formed when the lava flowed and inflated around an obstacle.

Credit: Christopher Hamilton.

By Lauren Lipuma

Planetary scientists are using a volcanic flow field in New Mexico to puzzle out how long past volcanic eruptions on Mars might have lasted, a finding that could help researchers determine if Mars was ever hospitable to life.

People don’t usually think of New Mexico as a volcanically active place, but it has some of the youngest (geologically speaking) large lava flows in the continental United States.

Christopher Hamilton, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona, has been studying one particular flow, the McCartys, for nearly 10 years. Hidden in plain sight along Route 66, the McCartys is part of a large volcanic flow field in New Mexico’s El Malpais National Monument that was erupted several thousand years ago. El Malpais, or the badlands, is so named for the desolate, rocky landscape it encompasses.

Hamilton and his colleagues are trying to understand how long it took for the McCartys flow field to be laid down, which will help them understand how past eruptions on Earth and Mars affected their planet’s ability to host life.

How long a lava flow lasts helps determine an eruption’s effect on a planet’s habitability. Lavas erupted quickly over days or weeks can release a lot of gas into the atmosphere and potentially alter a planet’s climate. But lavas erupted slowly over years or decades can release heat into the ground, which can warm groundwater and generate hydrothermal systems that support exotic forms of microbial life.

“I like to think about it like the tortoise and the hare,” Hamilton said. “You’re erupting the same amount of material, but is it done in this gradual process, or is done in a very fast process?”

Christopher Hamilton and colleagues use kites to study the McCartys lava flow field from the air.

Credit: Christopher Hamilton.

As lava advances, it inflates, just like rising bread. As the outermost lava cools, it forms a crust scientists can measure. In a new study in AGU’s Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, Hamilton and his colleagues measured how thick the McCartys crust is to estimate how long it took for the lava to grow. The thicker the crust, the longer the eruption lasted.

The McCartys flow is huge, covering about 310 square kilometers (120 square miles). The 2018 eruption of Hawaii’s Kilauea volcano was tiny by comparison: at its end, the eruption had covered about 35 square kilometers (14 square miles) of land with lava.

To study such a large area, the researchers mounted cameras on kites and collected extremely detailed images from the air.

“The kites became our personal satellites, acquiring high-resolution images to transform the observations we’re making on the ground into an aerial perspective so we can study other terrains on Mars,” Hamilton said.

Combining the kite images with measurements from the ground, Hamilton and his team estimate that the southern branch of the McCartys was laid down over the course of about two years, but as a whole, the eruption could have lasted for over a decade.

Because the McCartys flow was erupted over a long period of time, the researchers suspect similar lava fields on Mars were also erupted slowly. They argue that the thick lava flows of Mars’s Hrad Vallis—in some places as tall as a 20-story office building—were laid down over several decades. These flows likely contained enough heat to have sustained hydrothermal systems hospitable to microbial life for hundreds to thousands of years, according to Hamilton.

“Hrad Vallis has the potential to have interacted with water and generated hydrothermal systems,” he said.

The McCartys has attracted the interest of volcanologists for over a century, but it has many more secrets to tell about the geologic history of the Southwest and the search for life throughout the solar system.

Lauren Lipuma is a science writer and video producer at AGU.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

Glad to see that our old LPL field haunts at/on the Bandera Lava Field are being revisited!

Allen W. Hatheway, Research Associate (1967-1969)

in memory of Dr. Kuiper, Robert Strom, Alika Herring and Mr. Weiz, Mechanical Engineer

University of Missouri-Rolla (Retired)

Rolla, Missouri

(406-250-3376; mobile)