29 August 2017

Unprecedented levels of nitrogen could pose danger to Earth’s environment

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

A farmer and tractor tilling soil. New research finds that humankind’s contribution to the amount of nitrogen available to plants on land is now five times higher than it was 60 years ago, mainly due to increases in the synthetic production of fertilizer and nitrogen-producing crops.

Credit: USDA.

By Kelsey Simpkins

Humankind’s contribution to the amount of nitrogen available to plants on land is now five times higher than it was 60 years ago, mainly due to increases in the synthetic production of fertilizer and nitrogen-producing crops, according to a new study. This increase in nitrogen parallels the exponential growth of atmospheric carbon, the main culprit behind climate change, and could pose as much of a danger to Earth’s environment, according to the study’s authors.

Human production of fixed nitrogen, used mostly to fertilize crops, now accounts for about half of the total fixed nitrogen added to the Earth, both on land and in the oceans, according to the new study that provides updated estimates of the global nitrogen budget.

Fixed, or reactive, nitrogen is nitrogen that is taken out of the atmosphere and converted into a chemical form available for plants and animals to use as a nutrient.

The Earth has never seen this much fixed nitrogen, according to the study’s authors. Too much nitrogen can affect human health, reduce biodiversity and amplify global warming, they said.

“It’s a tremendous increase in the last half century, which is not what we were expecting to find,” said William Battye, an air quality researcher at North Carolina State University, in Raleigh, North Carolina, and lead author of the new study in Earth’s Future, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

Increased use of fertilizers and increased production of soybeans and other crops that convert atmospheric nitrogen into fixed nitrogen are significant contributors to excess nitrogen, according to the new study. Humans have become dependent on nitrogen-based fertilizers and nitrogen-fixing crops to sustain a high-level of global crop production, according to Viney Aneja, an air quality scientist at North Carolina State University and co-author of the new study.

Too much nitrogen in the soil benefits a limited number of species that can outcompete native species, reducing biodiversity. High levels of nitrogen in groundwater are associated with intestinal cancers and miscarriages, and can be fatal to infants. Excess nitrogen compounds in waterways and lakes can cause toxic algal blooms, killing off aquatic species and threatening human health, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

One form of nitrogen gas, nitrous oxide, is also a potent greenhouse gas and can contribute to global warming. High levels of nitrous oxide in the atmosphere also degrade the atmospheric ozone layer, and nitric oxide can create dangerous ground-level ozone, according to the study’s authors.

“While carbon has captured the attention of the world through climate change… we cannot ignore this issue [of nitrogen],” Aneja said.

Increasing nitrogen production

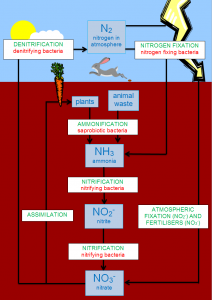

Nitrogen comprises 80 percent of Earth’s atmosphere in a form known as non-reactive nitrogen, where two nitrogen atoms are bonded together and don’t react with other elements or compounds. Lightning and certain types of bacteria convert this nitrogen gas into a biologically fixed state known as reactive nitrogen, where the nitrogen becomes available to plants to make proteins and other molecules essential for survival.

Bacteria then covert nitrogen-rich waste into simple nitrogen compounds. In a process called denitrification, specialized bacteria convert these simple nitrogen compounds into nitrogen gas and return it to the atmosphere.

This graphic shows how nitrogen cycles through the environment in its various forms.

Credit: Roseramona, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Humans have used nitrogen compounds as a fertilizer for millennia, but historically only used naturally-fixed sources, like manure and guano. In the early 1900s, German chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch discovered a process that converts atmospheric nitrogen to ammonia, allowing humans to produce nitrogen-based fertilizers on an industrial scale for the first time.

By 1960, more than 60 percent of farms in the U.S. reported using chemical fertilizer and average nitrogen use was 17 pounds per acre. In 2007, U.S. farms were using 82.5 pounds of nitrogen per acre on average, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

In the new study, researchers combined historical data on fertilizer use in agriculture with recent estimates of nitrogen-fixation rates to analyze trends in human production of fixed nitrogen since the beginning of the 20th century. They then placed these trends in context with recent estimates of natural nitrogen fixation and denitrification rates on land and in water.

The new study found human production of reactive nitrogen has increased almost five-fold in the last half-century. This rapid increase has removed any uncertainty about the importance of human-produced nitrogen on the overall nitrogen cycle, according to the new study.

Can denitrification keep up?

The study’s authors question if Earth’s current denitrification process can continue to keep up with the human production of fixed nitrogen.

Currently, the bacteria that drive this denitrification process seem to be keeping pace with the increased fixed nitrogen. But if the habitats where these bacteria thrive, such as marshes and wetlands, are not conserved, and the denitrification process breaks down, a major imbalance in the nitrogen cycle could occur. That could lead to harmful algal blooms and dead zones in water bodies, higher costs for drinking water treatment, and an increased risk to public health from algal toxins in waterways.

Even if the denitrification process can keep up with increasing demand, there could still be negative atmospheric consequences of the excess nitrogen, according to the authors. Denitrification produces nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas that is the third largest contributor to global warming after carbon dioxide and methane. Nitrous oxide has a greenhouse potential almost 300 times greater than carbon dioxide pound for pound and can last in the atmosphere for more than 100 years, according to the EPA. Nitrous oxide can also deplete the stratospheric ozone layer, Aneja said.

Nitric oxide, another byproduct of denitrification, can react with volatile organic compounds to produce ground-level ozone, which is harmful to humans and vegetation, according to the authors.

Human-caused climate change, a result of too much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, could also intensify the amount of nitrogen in U.S. waterways. Climate change could cause more rainfall in some areas, which could result in more agriculture runoff that can contaminate local waterways, according to a recent study in the journal Science.

— Kelsey Simpkins is a public information intern at AGU.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.