7 August 2017

New study details earthquake, flood risk for Eastern European, Central Asian countries

Posted by mjepsen

By Madeleine Jepsen

How will future disasters affect countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia?

Researchers aiming to answer this question used projected changes in population and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for 33 countries, along with climate, flood and earthquake risk models, to estimate how each country is affected by flooding and earthquakes now and in the future. In addition, the earthquake model was used to estimate fatalities and capital losses from a strong quake.

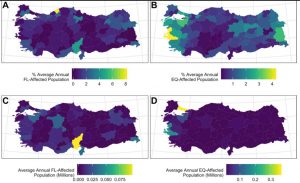

To assess how much a country would be affected by earthquakes and floods, the researchers determined how much of the country’s GDP or population met certain thresholds for risk. For the flood model, an area was considered affected if it experienced 10 centimeters (4 inches) of flooding. For the earthquake model, affected areas had to experience a “strong” earthquake, meaning people in the area would feel the earthquake, and it would be strong enough to move heavy furniture.

Of all the countries that were studied, Georgia has the largest percentage of its population likely to be affected by earthquakes in the future with Albania close behind. Both Georgia and Albania also had high percentages of their GDP likely to be affected by future earthquakes.

The research also suggests that by 2080, climate change-induced changes in flooding could result in Tajikistan and Mongolia experiencing the largest increases in the percentage of their populations affected annually by floods. Tajikistan is estimated to see an approximate 70 percent increase in flooding risk, and Mongolia could see an approximate 60 percent increase in risk.

The new research, published in Earth’s Future, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, could help organizations identify where to focus preventative efforts and additional risk analysis, according to the study’s authors.

“The results of the study are going to be used mainly to promote discussions with the governments within the countries to help them understand what their flood and earthquake risk might be, and perhaps moving on toward further discussion about how we can minimize the risk or protect against it, one way or another: financially, or through other development projects,” said Richard Murnane, lead author of the study and senior disaster risk management specialist with the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery at the World Bank.

Flooding and earthquakes, which can often mean death and destruction in the areas they impact, have been previously shown to have a much greater impact on developing countries’ economies than they do on industrialized countries’ economies, since industrial economies are often more diversified. However, all countries are subject to future increases in risk due to a variety of factors, including increases in hazards such as more extreme precipitation events, increases in exposure such as population and economic activity in hazardous areas, and increases in vulnerability such as unplanned or poorly-built structures.

Because of this increased vulnerability in countries like those in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, taking measures to protect these countries against flood and earthquakes is even more critical, the study’s authors said.

“In the policy world, people worry a lot about the impact of climate change and how that might affect risk, but an important factor that might dominate the changes in the future, depending on where you’re talking about, could be changes in exposure,” Murnane said. “You can have a huge increase in exposure that can be much more important with regards to risk than a change in hazard.”

To characterize flood and earthquake risk, the researchers focused on two factors that affect risk: hazard, or the likelihood of a flood or earthquake event with a specific intensity at a given location; and exposure, or the number of people or the GDP in an area. A third factor, vulnerability, which considers how the exposure is affected by a hazard event, was explicitly considered in the earthquake model through estimates of fatalities and capital losses.

The researchers also looked at whether future changes in flood risk are the result of changes in exposure – changes in a country’s GDP or population – or changes in the hazard, in this case flooding, using a combination of possible socioeconomic scenarios and climate change models.

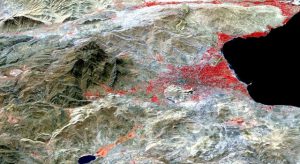

The researchers used Turkey as an example of how different provinces within a country may face different risk levels.

Although the research focused on identifying risk at the national level, the results also indicated the risk to people and economies from a flood or earthquake could vary greatly within a single nation. Murnane said more localized research is necessary to identify areas of risk within specific countries, but the modeling used in the new study showed different levels of provincial risk.

“You can have a very wealthy province, and have $100 million dollars of its GDP affected by a hazard event,” Murnane said. “It’s a lot of money but if there are billions worth of GDP in that province, it’s relative impact won’t be as large as it would be for a poorer province. The same size loss could be 90 percent or more of the GDP for that poorer province. That would have a much greater impact for the people in that province than for those in a wealthier province.”

The study’s predictive ability has limitations. For example, the models could not account for unexpected changes in population distributions, nor do they include already-established flood defenses. But Murnane said the results could be a helpful tool for identifying where intervention efforts will make the biggest difference in lowering risk.

“As a first-order assumption, you can use the relative changes in flood risk to prioritize which countries to focus on.” Murnane said. “For a country with a large climate change-induced increase in flood-affected population, you might want to assess existing flood defenses or determine other actions that might need to be taken at a more local level.”

— Madeleine Jepsen is a science writing intern at AGU.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.