19 May 2017

New technique provides earthquake risk for major cities worldwide

Posted by larryohanlon

By Larry O’Hanlon

CHIBA, JAPAN – Scientists have developed snapshots of the likelihood of major earthquakes occurring in megacities around the world using a new statistical approach for estimating earthquake risk.

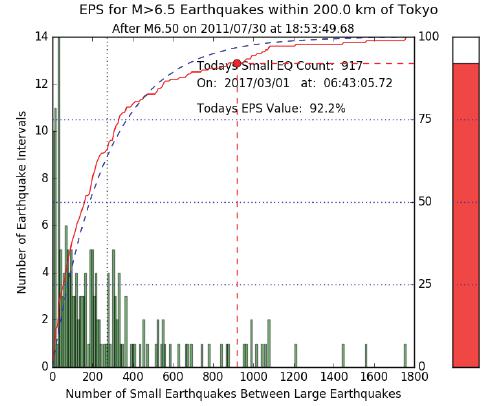

The new technique, called seismic nowcasting, estimates the progress of a defined seismically-active geographic region through its repetitive cycle of major earthquakes. Applied to cities, the method assigns an Earthquake Potential Score, or EPS. The EPS provides a snapshot of the current risk of a major earthquake occurring in a region, and gives scientists, city planners and others a thermometer to see where a city is in a major earthquake cycle.

Using the new technique, scientists determined that the EPS for Lima is about 70 percent; Manila, Taipei and Tokyo have an EPS of about 90 percent; Los Angeles and San Francisco have an EPS of about 50 percent, and Ankara has an EPS of about 30 percent. This means Los Angeles is about half-way through its cycle for 6.5-magnitude or greater earthquakes, while Tokyo is about 90 percent of the way through its cycle.

A nowcasting analysis for Tokyo. The red thermometer at right shows haw far along the region is in its cycle of smaller quakes between quakes of at least 6.5 magnitude, within 200 km radius and 100 km depth. Source: Rundle, et al 2017.

A region’s EPS can be seen as a way of estimating how much tectonic stress has built up in the Earth’s crust since the last large earthquake – a notoriously difficult question for seismologists to answer. The new method does not provide an estimate of when in the future a large earthquake might occur.

“EPS is the thermometer,” said John Rundle, a seismologist at the University of California Davis, who is presenting the new research at the JpGU-AGU joint meeting next week. “It’s meant to be for city planners to see where they are in the cycle of major earthquake within a defined geographic region.”

The nowcasting method uses the number of small earthquakes that have occurred in a region since the last large earthquake to statistically work out progress through the regional earthquake cycle. The trick, says Rundle, is to first look at the past earthquake data for a larger region, then apply it to a smaller area within that region.

For example, seismological records of a large region, like all of California and Nevada, show a range of earthquakes of various sizes, with smaller quakes being more common. This information is compared to the number of small earthquakes that have occurred since the last big earthquake in smaller regions, as, for example, within 100 kilometers (62 miles) around Los Angeles. Applying the earthquake distribution for the larger region to the smaller region gives scientists an idea of how far along the region is in its cycle of smaller quakes relative to large earthquakes.

Rundle stresses that the new technique is not a model, only an interpretation of current data to provide the current earthquake status of a region. It does not forecast when a future major earthquake might occur.

— Larry O’Hanlon is a freelance science writer, editor and social media manager in New Mexico. He manages the AGU blogosphere. Follow him on Twitter at @Earth2larryo. This new research being presented Monday, May 22 at the JpGU-AGU joint meeting in Chiba, Japan.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.