2 May 2017

Development degrades Canary Island’s cherished sand dunes (+video)

Posted by Nanci Bompey

By Brendan Bane

The Maspalomas dune fields stretch just below the horizon of the Atlantic Ocean. Sediment flows from ocean waters and is carried across the dunes by wind, but that process can be interrupted by a developing cityscape.

Credit: Himarerme/Public Domain

Wind is powerful. Given enough time, steady gusts are strong enough to carve landscapes, from The Wave in Arizona to the limestone swirls of Texas. But putting homes and buildings in the wind’s path can disrupt this terrain-altering process, and even degrade cherished natural features, a new study suggests.

The new study, published in Earth’s Future, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, explores the impact of development on local wind patterns and dune formation on one of Spain’s Canary Islands.

By reviewing aerial photographs and topographical measurements, the study’s authors watched how a city’s expansion altered local wind patterns and ultimately changed the surrounding landscape, jeopardizing the long-term sustainability of a major tourist destination.

The study took place on the resort island of Gran Canaria, the second-most populated of the Canary Islands. Every year, thousands of tourists flock to the island’s most popular attraction: the Maspalomas Dunes. The golden, rolling dunes span roughly 1,000 acres south of Maspalomas city, comprising a Martian-like landscape on the island’s southern coast. The dunes were designated a nature reserve in 1897, and tourists often sunbathe along the soft, sandy crests.

But some of Maspalomas’s dunes could disappear in fewer than 130 years, in part because of changes to regional wind patterns caused by city development, according to Alexander Smith, an environmental scientist at Ulster University’s School of Geography and Environmental Science in Northern Ireland, and lead author of the new study.

“The long-term sustainability of the dune field is now in question because of the negative feedback from urbanization,” Smith said. “Without major changes, I’m not sure this can be reversed.”

Smith used aerial photos of the dunes dating back to 1961, before development of Maspalomas first began. The photos revealed how the extent of vegetation and exposed sand changed over the decades. Smith supplemented those photos with topographic measurements taken between 2006 and 2011, which depicted changes in the height and shape of the dunes.

Maspalomas is home to hundreds of tourists throughout the year, who flock to the resort town to see the nationally cherished dune fields.

Credit: NASA.

Smith then plugged those measurements into a model of the Maspalomas cityscape, estimated where the wind’s course had been altered, and how that may have influenced the evolution of the dunes.

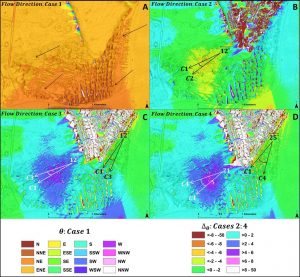

The buildings had a dual effect, intensifying wind flow upwind of the city and dulling it in the downwind area. Winds generally flow northeast to southwest across Maspalomas. But the city’s southernmost edge now acts as a shield, diverting and concentrating winds downward while blocking gusts and new sediment from reaching the city’s western side.

This dual effect degrades the dunes in two ways: the downwind area receives so little wind that plants have colonized its quieted hills, while the upwind area loses sand faster than natural processes can replenish it. According to Smith, Maspalomas’s sediment budget—the proportion of sediment flowing into a system versus the sediment leaving it—is now in a state of deficit.

Dunes that receive intensified winds could be fully depleted of sand within 130 years, Smith said. This exacerbates an already stressed area, as recent storms are eroding adjacent shores faster than incoming sediment can restore them. In contrast, dunes shielded from wind were blanketed by a 300 percent spike in plant coverage over the past 50 years.

Winds once flowed northeast to southwest across Maspalomas, as pictured in cell A. But the city’s southernmost edge redirects those gusts, concentrating them onto some dunes and blocking them from others, as pictured in cells B, C and D. Credit: Alexander Smith

Smith hopes future developers will consider his findings when designing cities alongside coastal or arid regions like Maspalomas’s dunes. By incorporating aerodynamic designs or spacing buildings farther apart, some of the buildings’ effects on wind may be negated, Smith suggested.

— Brendan Bane is a freelance science writer.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.