21 December 2016

New study differentiates between Utah’s natural and induced earthquakes

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

Utah is home to unique topographical features, like these buttes, but many were created by erosion rather than shifting tectonic plates.

Credit: Sukee Bennett.

By Sukee Bennett

Mining activity caused nearly half of all earthquakes in Utah over the past three decades, according to a new study. By studying the epicenters of 6,846 earthquakes occurring in the state between 1982 and 2016, scientists at the University of Utah determined 3,957 of them occurred naturally and 2,889 were caused by coal mining.

Compared to their tectonically driven, natural counterparts, human-caused earthquakes are typically minor events. But two years ago, a magnitude-5.7 earthquake—catalyzed by the wastewater injection process of fracking—hit Oklahoma, injuring two people and damaging homes and roads. Human-caused earthquakes can happen when sediment is added or removed from the ground. In Utah, human activity, particularly coal mining, removes sediment from the ground, changing the stress on faults and potentially triggering earthquakes.

“When you take out mass, you change the state of stress in the earth,” said Keith Koper, a seismology professor at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City and the lead author of a new study published in Geophysical Research Letters and presented at the 2016 AGU Fall Meeting in San Francisco. “That causes earthquakes—little baby earthquakes.”

Utah’s natural earthquake risk is often overlooked compared to West Coast states like California, but the inland state has faults of its own, Koper said. The faults meander from Arizona into Utah and upward to Montana and Yellowstone National Park. They’re responsible for much of the West’s unique topography, he said.

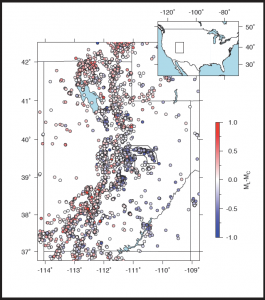

Koper and his team of undergraduate and graduate students mapped out the magnitude of Utah quakes to differentiate between those caused by coal mining—what scientists call “mining-induced events”—and those with natural, tectonic origins.

Map of the epicenters of 6,846 earthquakes occurring in Utah from 1982 and 2016. Those depicted in red were naturally caused tectonic plates, whereas coal mining caused those in blue.

Credit: Keith Koper.

Segregating natural quakes from human-caused ones, a practice called “seismic discrimination,” is important work, he added. Scientists are currently working on seismic hazard maps of Utah: tools that predict when a high-magnitude earthquake may rumble, depending on the abundance of smaller ones. When many small earthquakes occur, a larger one is likely to follow, Koper said. But mining-induced events, which do not signify a larger earthquake is on the way, can confuse researchers generating hazard maps. If they count mining-induced events as tectonic earthquakes, they could predict larger earthquakes more frequently than they should, Koper said.

Koper and his team solved this problem. Using more than 200 seismometers that engineers began employing throughout Utah in the 1960s, the researchers studied the epicenters of Utah’s earthquakes over the past 34 years. They used both the Richter magnitude and the duration magnitude scale when looking at each earthquake.

Tectonic earthquakes originate at a much greater depth than mining-induced events, which strike closer to Earth’s surface. Deeper earthquakes also generally have higher magnitudes. By subtracting the duration magnitude from the Richter magnitude, the team calculated the depth of each earthquake, and used this information to differentiate between naturally-occurring and human-induced earthquakes.

“The difference in magnitude was really good at telling the difference in depth between the two types of quakes,” said Koper.

The method of differentiating between tectonic and coal mining-induced earthquakes used in the study could have other applications, said Emily Brodsky, a seismology professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who was not involved in the study.

“It might not be a bad way to discriminate volcano events, too,” she said. “It’s a good angle.”

—Sukee Bennett is a science communication graduate student at the University of California Santa Cruz. Follow her on Twitter at @Sukee_B.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.