8 December 2011

Japanese megaquake triggered tiny California tremors

Posted by kramsayer

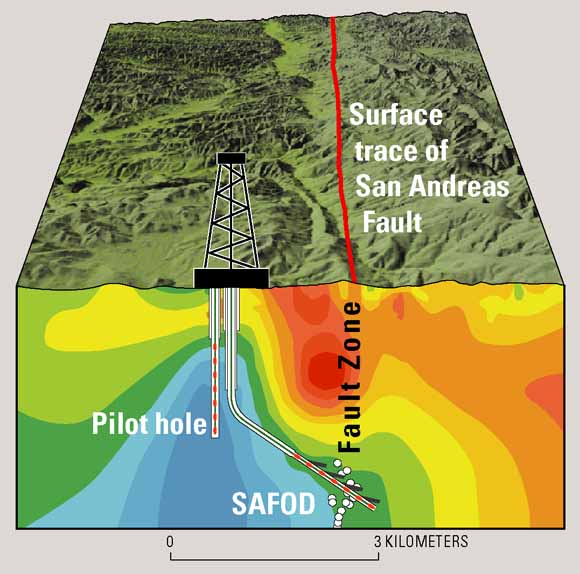

A dense network of underground seismic sensors — including some at the San Andreas Fault at Depth (SAFOD) — pick up the tiniest tremors at Parkfield, Calif. (Credit: U.S. Geological Survey)

As southern Californians absorbed the news of the devastating March 11 earthquake in Japan, seismic instruments under their feet sensed the shocks as well.

The magnitude-9.0 Tohoku-Oki megaquake triggered tremors deep below California, roughly 8,500 kilometers (5,280 miles) away from Japan, according to seismologist David Hill of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Menlo Park, Calif., and his colleagues.

“A big earthquake like that sets the whole Earth ringing and resonating for hours,” Hill said.

Sensors in Japan and Cascadia, Wash., have previously detected earthquake-triggered tremors, usually in response to low-frequency waves traveling along the Earth’s surface. But at the American Geophysical Union’s Fall Meeting, Hill’s team reported one of the first examples of tremors triggered by higher-frequency components of earthquakes, known as S-waves.

Waves from the Japanese temblor registered as tiny pressures along the San Andreas Fault in Parkfield, Calif., — pressure about equal to rubbing your thumb and forefinger together. When spread along an entire fault line, though, especially one as volatile as San Andreas Fault, the minute pressures packed a powerful punch.

Underground seismometers jumped after the first S-wave arrival from Japan, and twitched again following a second set of S-waves about four minutes later. Finally, tremor activity fluttered in lock-step with slow-arriving surface waves as they swung back and forth — a correspondence too close to be a fluke, USGS seismologist David Shelly, a co-author of the poster, said.

Compared to resting vibrations inside the Earth, the tremors Hill and his colleagues measured along an 80-kilometer (50-mile) stretch of the fault stood out like a shout amidst a mumbling crowd. The tremors were too small, however and at 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) too deep to be felt on the surface.

So why are the puny tremors a big deal to seismologists? By analyzing interactions between existing underground pressures and incoming seismic waves, the researchers could learn more about what causes a cranky fault to finally blow off some stress, Hill said.

“We want to understand the physical and chemical processes,” he said. “Why are earthquakes triggered in one place and not another?”

– Helen Shen is a science communication graduate student at UC Santa Cruz

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

[…] a mega-quake in Japan withsmall ones in California keeps showing me that there is a lot still out there to learn about on this […]